Being on the move

(Poet's title: Das Wandern)

Set by Schubert:

D 795/1

[October to November 1823]

Part of Die schöne Müllerin, D 795

Das Wandern ist des Müllers Lust,

Das Wandern!

Das muss ein schlechter Müller sein,

Dem niemals fiel das Wandern ein,

Das Wandern.

Vom Wasser haben wir’s gelernt,

Vom Wasser!

Das hat nicht Rast bei Tag und Nacht,

Ist stets auf Wanderschaft bedacht,

Das Wasser.

Das sehn wir auch den Rädern ab,

Den Rädern!

Die gar nicht gerne stille stehn,

Die sich mein Tag nicht müde gehn,

Die Räder.

Die Steine selbst, so schwer sie sind,

Die Steine!

Sie tanzen mit den muntern Reihn

Und wollen gar noch schneller sein,

Die Steine.

O Wandern, Wandern, meine Lust,

O Wandern!

Herr Meister und Frau Meisterin,

Lasst mich in Frieden weiter ziehn

Und wandern.

Being on the move is such a delight for the miller,

Being on the move!

It must be a terrible miller

Who never had the idea of being on the move,

On the move!

We have learned it from the water,

From the water!

Which never rests day or night,

It is always committed to being on the move,

The water.

We can see the same thing with the wheels as well,

The wheels!

Which never want to stand still,

Which never tire all day as they keep going,

The wheels.

The stones themselves, despite their heavy weight,

The stones!

They dance in a cheerful pattern

And they want to move even more quickly,

The stones.

Oh, being on the move, on the move, my delight,

Oh, being on the move!

Dear master and mistress

Let me go off in peace

And be on the move.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Dancing Mills Walking and wandering Weight – light and heavy Wheels

We begin with a paradox. The miller wants to be on the move; he feels constrained with his current master and mistress and he is seeking permission to leave. He wants to ‘wander’. However, he is not asking to wander around aimlessly. He does not ask to be ‘as free as a bird’. His model is the water, which runs in established channels, in a clear direction. His model is the mill wheel and the mill stone, both turned by the water (directly or indirectly), and fully restricted in their movements.

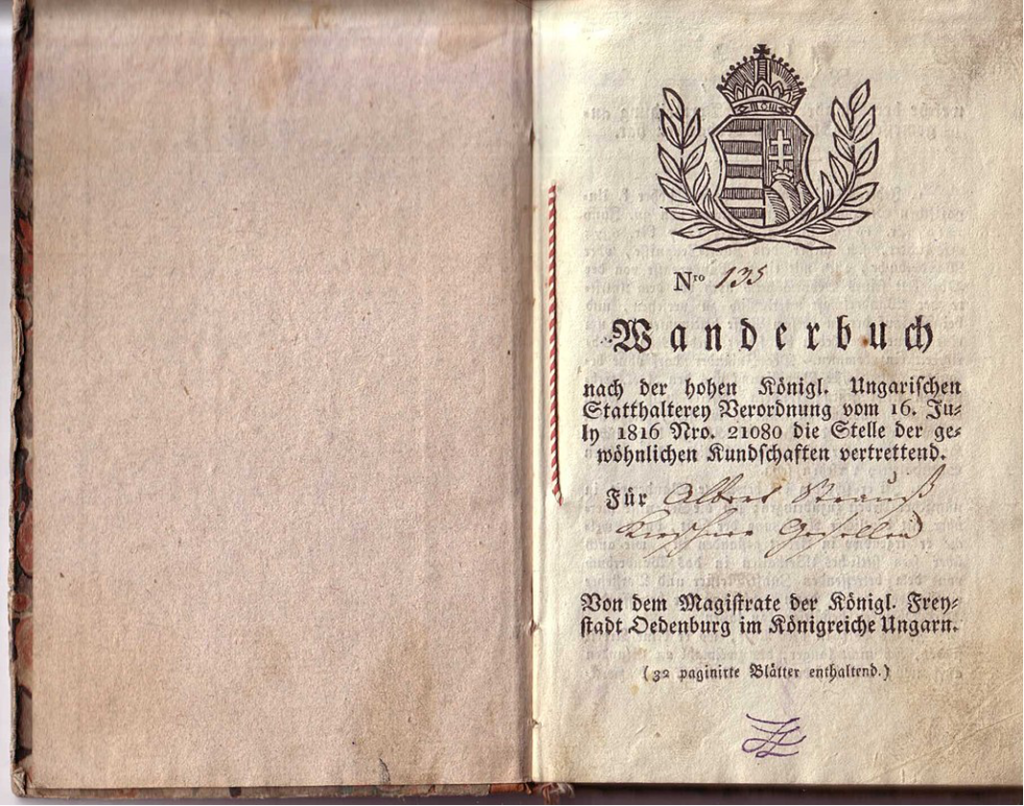

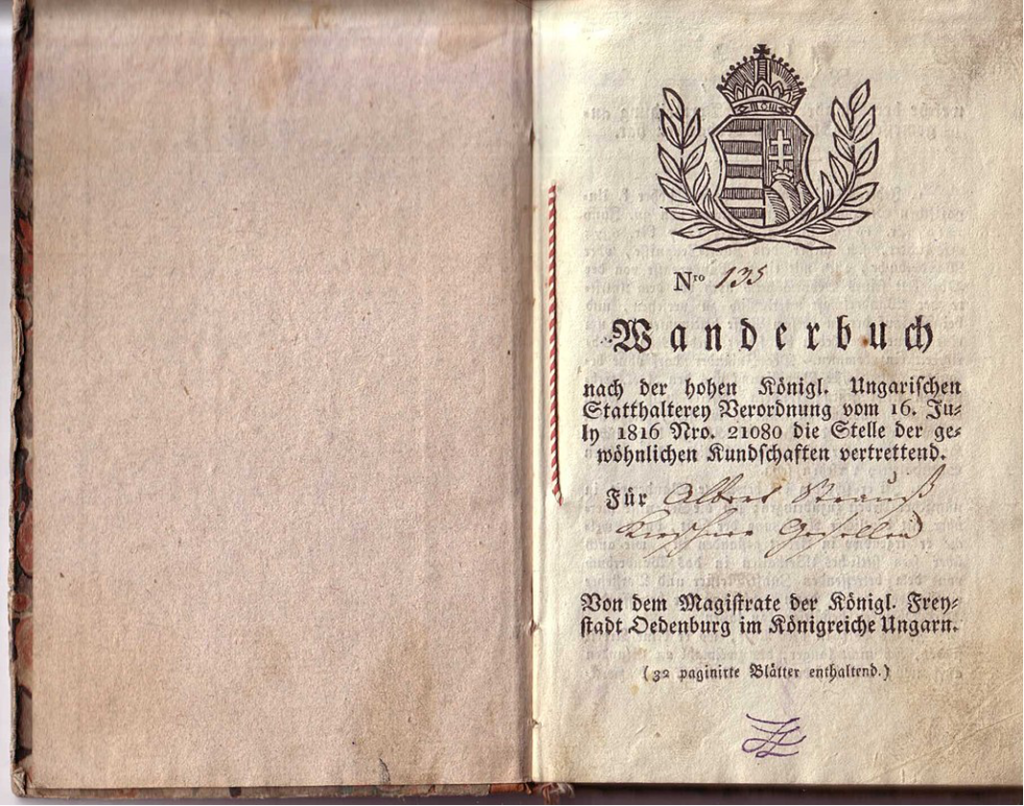

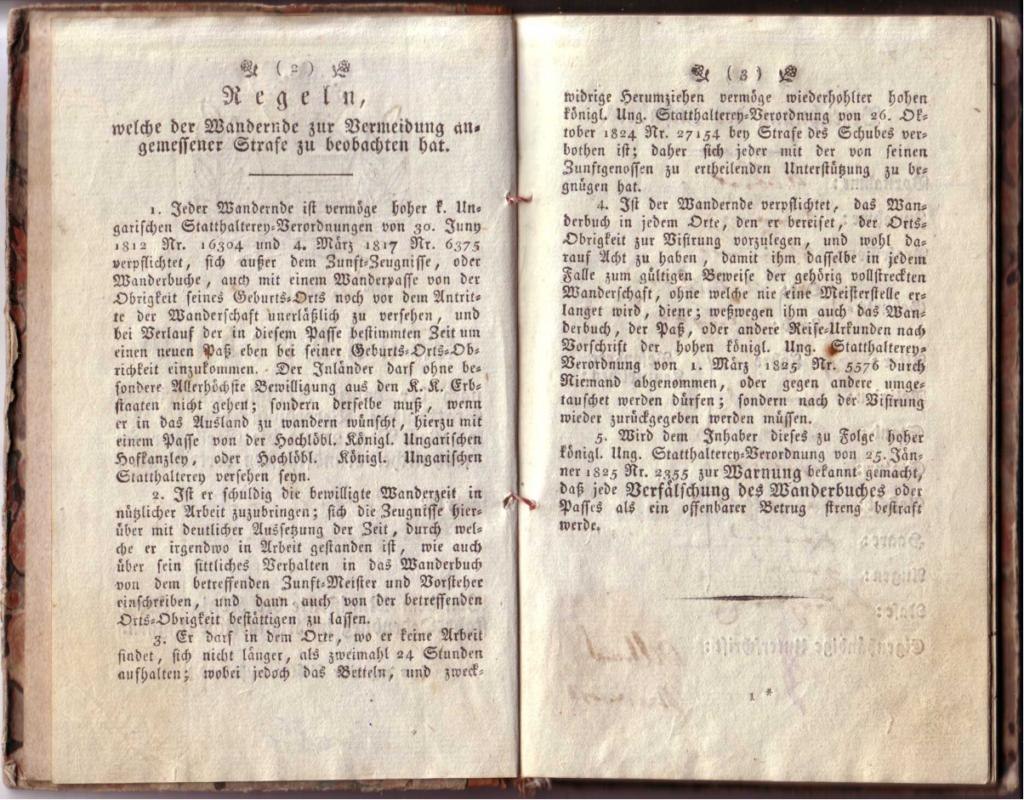

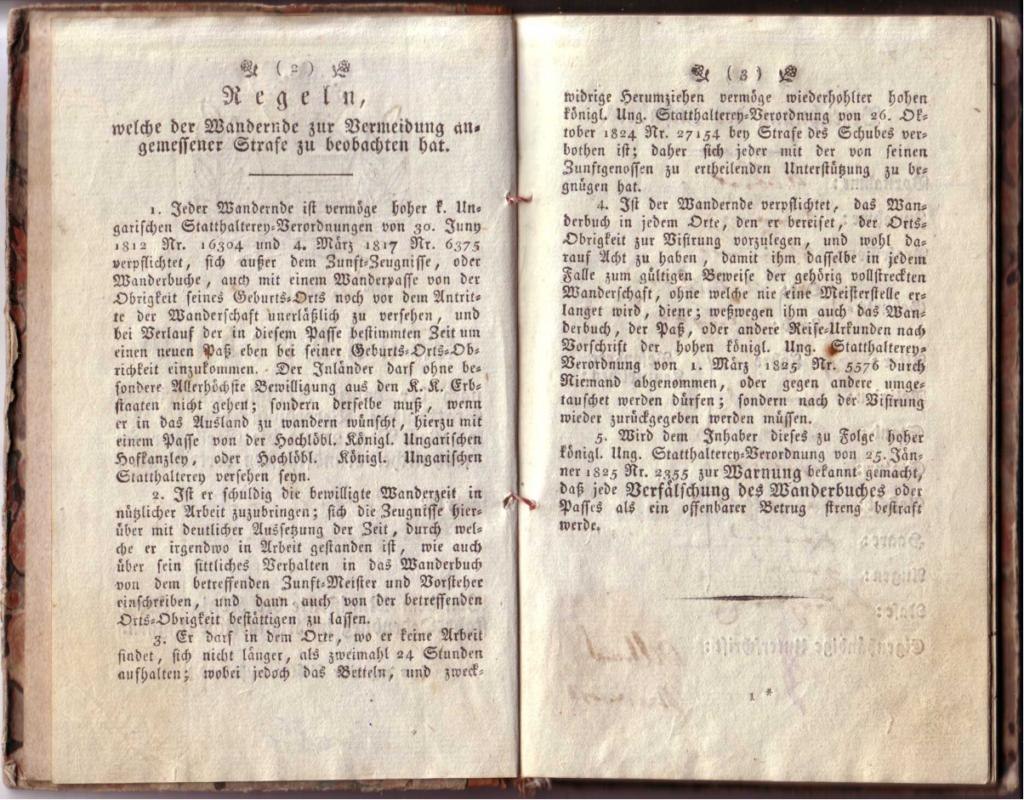

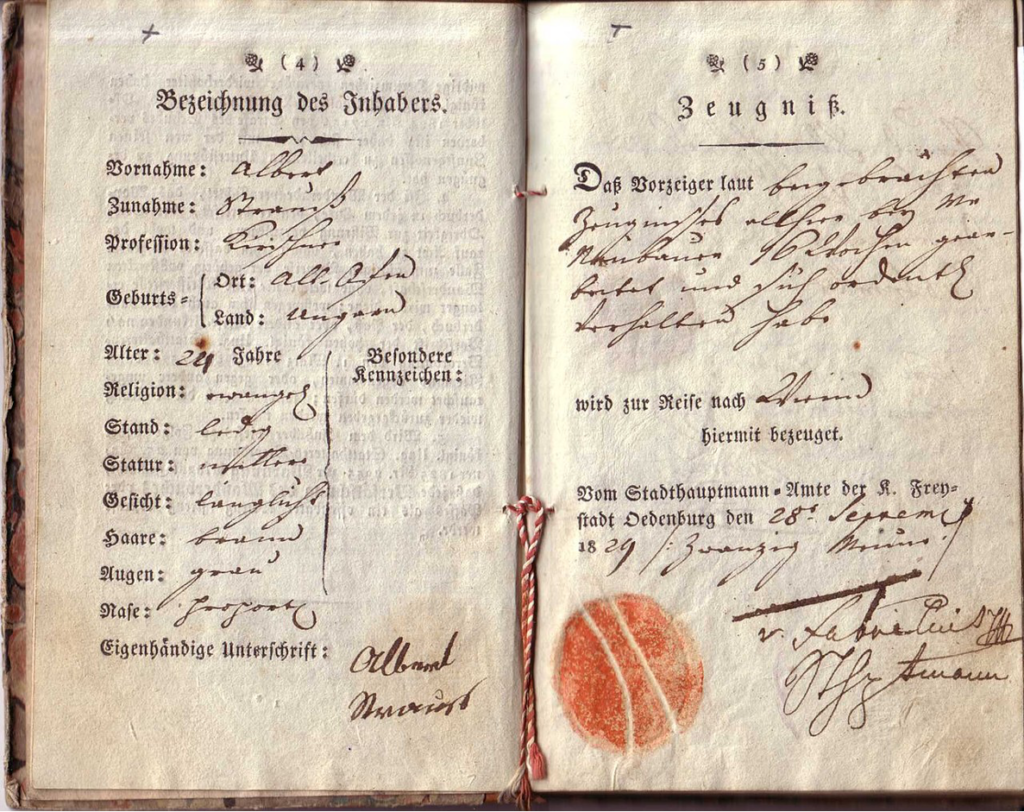

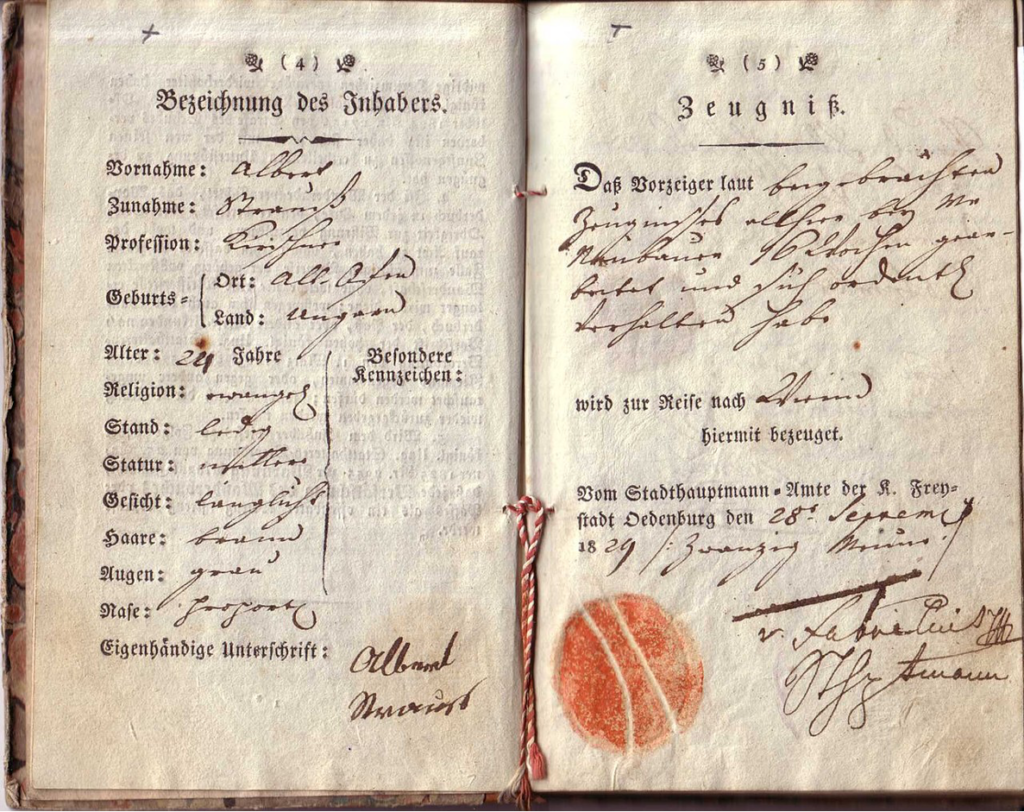

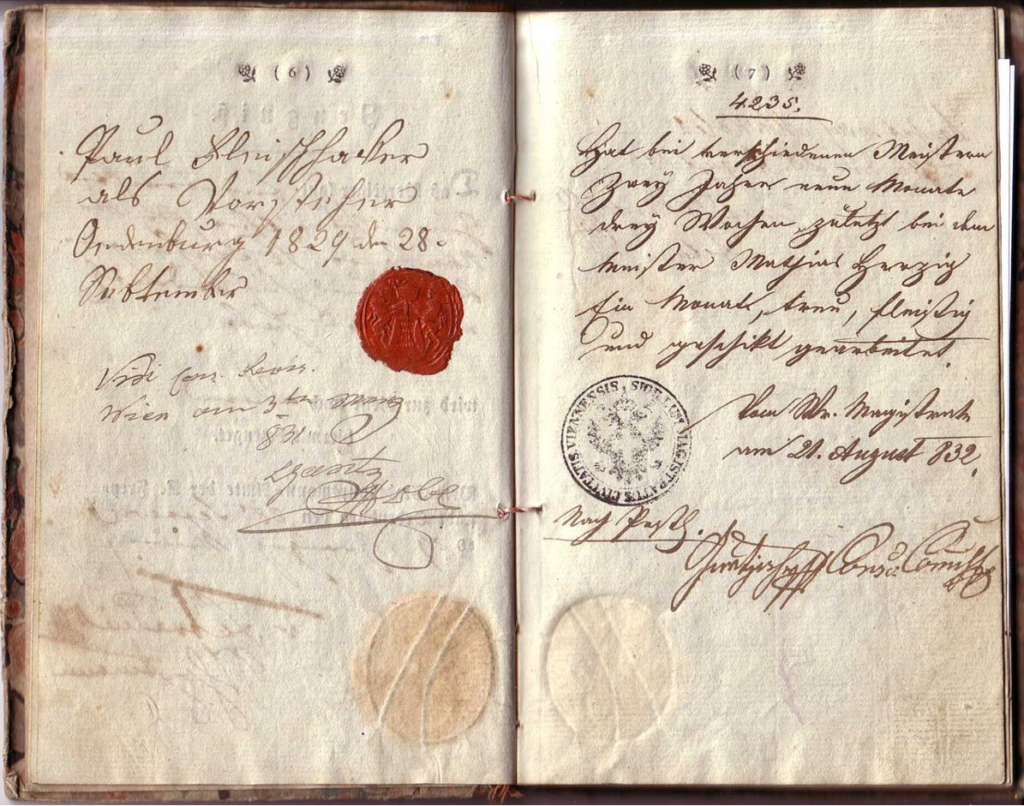

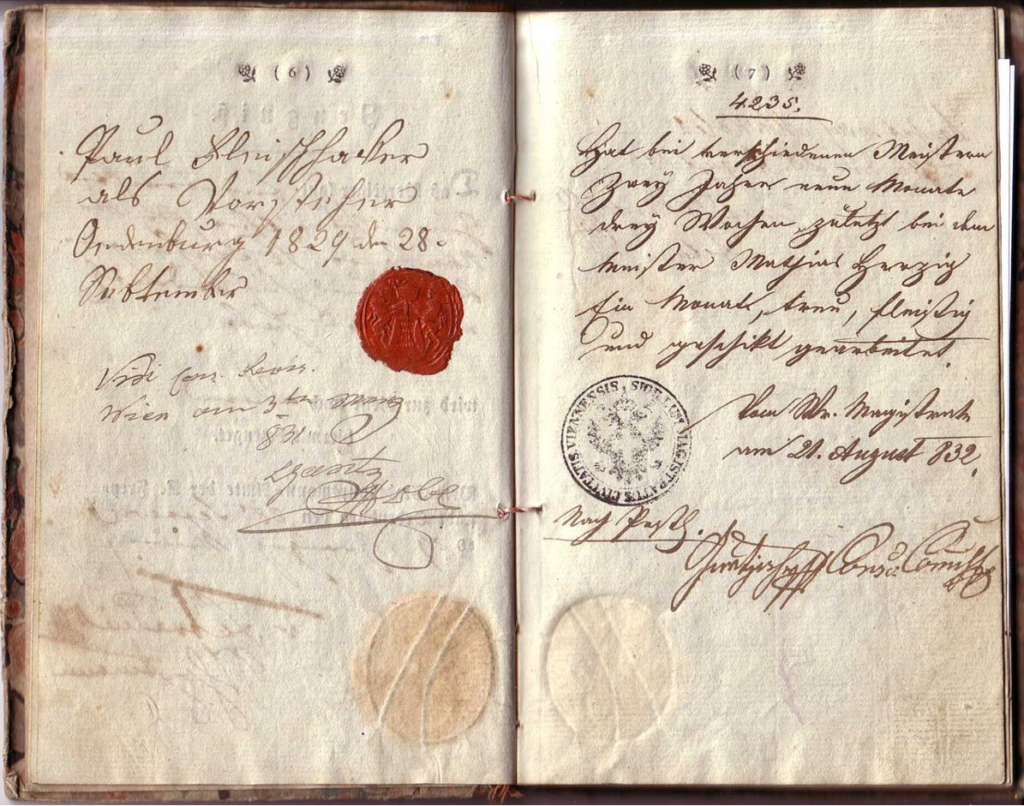

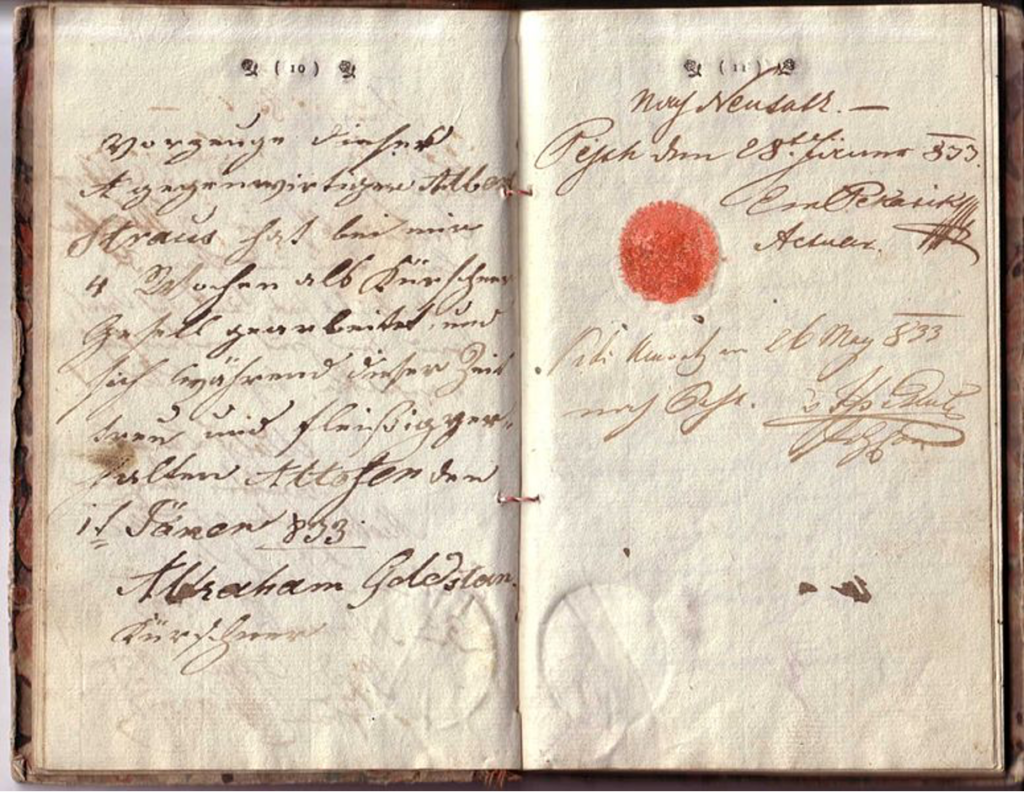

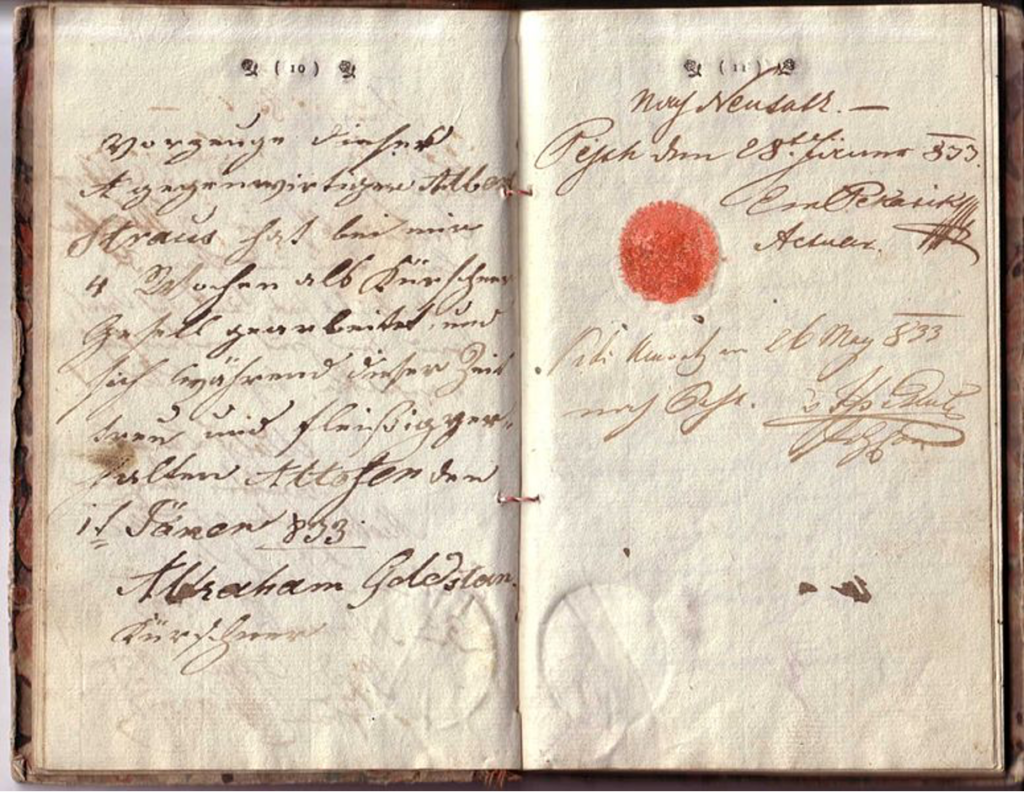

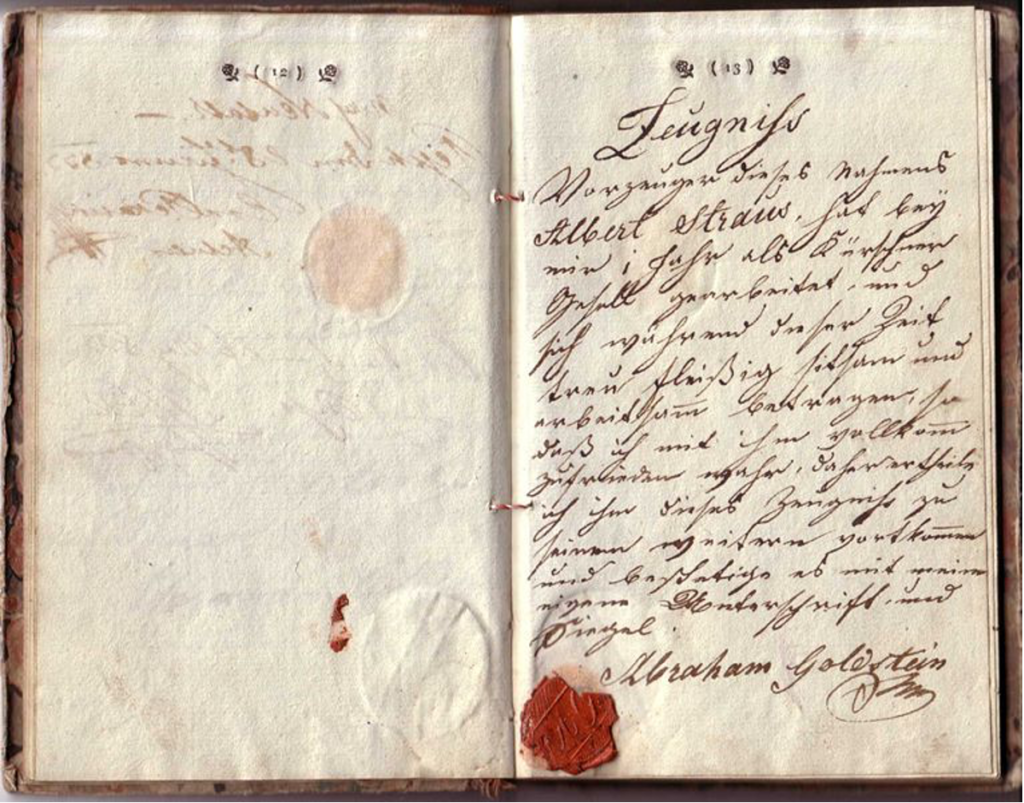

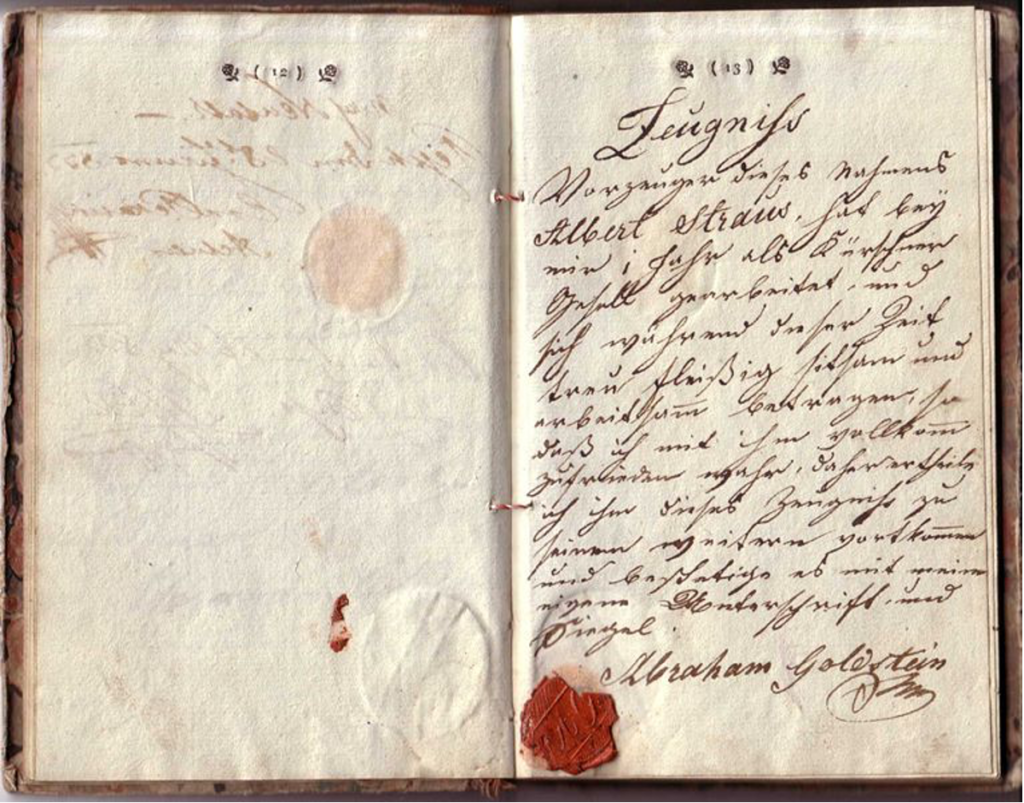

He is beginning that stage of development known as the ‘Wanderjahre’, the years of wandering, or the journeyman stage. Before the Industrial Revolution transformed German-speaking societies later in the 19th century, there were fixed codes and conventions for young men to follow after they left the early stage of their apprenticeship, their ‘Lehrjahre’ (learning years), when they lived with and learned the basics from an established master. The ‘wanderers’ wore a distinctive uniform and were expected to travel around working as day labourers (by the ‘journée’, hence ‘journeymen’) in at least three different regions (at a time when there were many dozens of principalities, towns and bishoprics which counted as separate jurisdictions). Most were expected to travel for three years and a day (and return with no more money than the small amount they had set out with) before they could return home and set themselves up as an established master in their own right. In some parts of the German-speaking lands the expectations were formulated more explicitly. An extraordinary document survives from Sopron / Ödenburg in the Kingdom of Hungary: the official ‘Wanderbuch’ of Albert Strauß, a furrier, who left the town as a ‘wanderer’ in 1829. These 32 pages set out the rules of ‘wandering’ (as decreed in 1816) and have sections to be filled in by the various employers who take him on as a journeyman.

The same tension between structure and freedom can still be seen by walkers in rural areas of Germany, Switzerland and Austria today. As hikers leave the towns, they are encouraged to follow signs marking ‘Wanderwege’ – walking routes. These are almost invariably prescribed paths, and the expected time it will take to reach the destination will be marked. Many English-speakers find this an odd approach to the idea of ‘wandering’, but it is important to realise that the German verb ‘wandern’ is not an exact equivalent of the English word ‘to wander’.

Another term used to refer to this itinerant stage of being an apprentice was being ‘auf der Walz’. The verb ‘walzen’ originally meant something like ‘to turn’ or ‘to roll’, so the young man who sets off to ‘wander’ for three years and a day is seen as ‘rolling around’ before he turns back home. The noun ‘Walzer’ began to refer to a specific dance, the waltz, after about 1790, but it is not clear if Müller is referring to this in stanza 4 of ‘Das Wandern’. He says that the millstones have joined in a sort of line dance (Sie tanzen mit den munten Reihn), but the main point seems to be that despite their weight, the stones are moving. Inevitably, though, they are moving in fixed and predictable patterns.

This is reflected in the verse form, with the tension between (a) the repeated words, which seem to establish a groove from which the speaker cannot escape and (b) the rhyming couplet, which seems to set things in motion and promises some sort of escape. In the end, though, the poem is cyclical, as cyclical as the mill wheel and the mill stones. The young lad is setting off, but he cannot escape.

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text Das Wandern Das Wandern ist des Müllers Lust, Das Wandern! Das muß ein schlechter Müller sein, Dem niemals fiel das Wandern ein, Das Wandern. Vom Wasser haben wir's gelernt, Vom Wasser! Das hat nicht Rast bei Tag und Nacht, Ist stets auf Wanderschaft bedacht, Das Wasser. Das sehn wir auch den Rädern ab, Den Rädern! Die gar nicht gerne stille stehn, Die sich mein Tag nicht müde gehn1, Die Räder. Die Steine selbst, so schwer sie sind, Die Steine! Sie tanzen mit den muntern Reihn Und wollen gar noch schneller sein, Die Steine. O Wandern, Wandern, meine Lust, O Wandern! Herr Meister und Frau Meisterin, Laßt mich in Frieden weiter ziehn Und wandern. 1 Schubert changed Müller´s 'drehn' (they keep turning) to 'gehn' (they keep going)

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Erstes Bändchen. Zweite Auflage. Deßau 1826. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, pages 6-7; and with Sieben und siebzig Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Dessau, 1821. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, pages 7-8.

First published in a slightly different version with the title Wanderlust in Gaben der Milde. Viertes Bändchen. Mit Beiträgen von […]. Für die Bücher-Verloosung “zum Vortheil hülfloser Krieger” herausgegeben von F. W. Gubitz. Berlin, 1818, pages 214-215.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 7 [Erstes Bild 17] here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10115224