Gondola rider

(Poet's title: Gondelfahrer)

Set by Schubert:

D 808

[March 1824]

D 809

for TTBB quartet and piano[March 1824]

Es tanzen Mond und Sterne

Den flücht’gen Geisterreihn:

Wer wird von Erdensorgen

Befangen immer sein!

Du kannst in Mondesstrahlen

Nun, meine Barke, wallen,

Und aller Schranken los

Wiegt dich des Meeres Schoß.

Vom Markusturme tönte

Der Spruch der Mitternacht:

Sie schlummern friedlich alle,

Und nur der Schiffer wacht.

The moon and the stars are dancing

In a fleeting, ghostly formation:

Does anyone want earthly cares

To shackle them for ever?

In the moonbeams you can

Drift now, my skiff;

And freed from all constraints

You are lulled in the lap of the sea.

Ringing out from San Marco’s bell tower came

The chimes of midnight:

Everyone is sleeping peacefully

And only the boatman is awake.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Bells Boats Chains and shackles Clocks Dancing Lap, womb (Schoß) Midnight Mirrors and reflections Night and the moon On the water – rowing and sailing Prisons and dungeons Rocking Sleep Stars The sea

A gondola, being a small boat without a mast, can be referred to in German as ‘eine Barke’ (though a ‘barque’ in English would be a large, three-masted sailing ship). Having embarked on such a vessel one can then sing a barcarolle, such as Mayrhofer’s ‘Gondelfahrer‘ itself. There is some doubt about who is singing the song on this occasion, though. Most translators assume that the ‘Gondelfahrer’ (and thus the singer) is a ‘gondolier’, and this seems to be supported by the last line of the text (he is the only person awake). However, gondoliers are unlikely to be out on the lagoon at night without passengers and it makes more sense to see the text as the thoughts of someone taking a gondola ride. Indeed one of the first people to hear Schubert’s setting of the poem (Moritz von Schwind[1]) gave the title of the song as ‘Gondelfahrt’ (gondola ride) rather than ‘Gondelfahrer’, which might support the suggestion that the speaker of the poem is reflecting on the experience of being taken for a ride. This would mean that the gondolier is the only other person in Venice who is awake.

Let us assume, then, that we are listening to the voice of a passenger on a gondola late at night out on the Venetian lagoon. Spread out all around are the ripples of the waves and undulations caused by the motion of the oar. The reflections of the moon and the stars therefore have the regularity of a dance along with the transcience that results from the ever changing motion and the uneven surface of the water:

Es tanzen Mond und Sterne

Den flücht’gen Geisterreih’n

The moon and the stars are dancing

In a fleeting, ghostly formation

Perhaps the passenger is leaving a ball in one of the palazzi and these reflections form a sort of echo of the dancing earlier in the evening. The poet gets the impression that the carefree mood of the dance is now shared by the rest of the world, that there is no need to remain shackled to the earthly concerns which had presumably driven him to Venice and its pleasures in the first place.

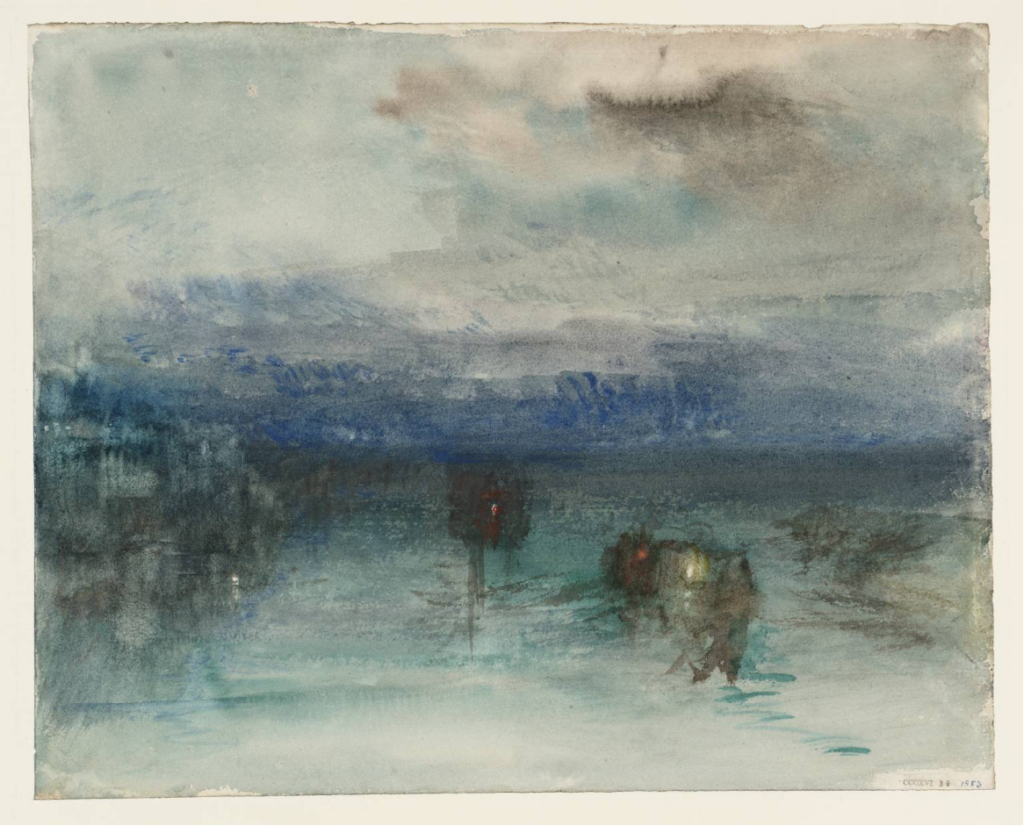

Joseph Mallord William Turner

London, Tate

The idea of chains and imprisonment introduces a darker note to the text, though. It reminds us that one of the most famous sights of the city has always been the Bridge of Sighs at the Doge’s Palace. Prisoners taken over it to the cells beyond knew enough about what was in store for them to emit sighs of despair as they crossed. The Venetian Republic was always an oppressive police state and Napoleon was able to present himself as a liberating figure when he defeated it in 1797. The image of Venice as using a superficial facade of beauty and pleasure to hide an ugly underside of arbitrary power and violence had already been reinforced with the publication in 1788 of Casanova’s account of his escape from the Doge’s prison: Histoire de ma fuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu’on appelle les Plombs (The story of my escape from the prisons of the Republic of Venice known as ‘the leads’). Many of the early readers of Mayrhofer’s poem would have been familiar with this story and might have interpreted the poem as the voice of someone (like Casanova) who had just escaped from the notorious prison behind the Doge’s Palace. They would have shared his delight at his victory over the forces of oppression. As the get-away gondola took him out onto the lagoon towards the open sea, they would have relished the Enlightenment idea that the powers of the state and convention could be defeated by human determination to be free.

Mayrhofer’s original readers would have been even more acutely aware that Napoleon’s ‘liberation’ of Venice had been short lived. After the Congress of Vienna (1815) Venice came under the control of the Habsburg Empire. It was thus subject to an even more repressive regime, which added religious (Catholic) conformity to its demands for political obedience. The autocrat in charge of this crackdown was the reactionary Austrian Chancellor, Klemens von Metternich. Censorship was a central strand of Metternich’s system, and one of his censors was none other than the poet of ‘Gondelfahrer‘, Johann Mayrhofer!

Although Mayrhofer was far from alone as a liberal working in a system that imposed illiberal censorhip, there is evidence that he felt the strain of his situation very acutely. His own writing explored the nature of freedom in other cultures (mainly in ancient Greece) but this may not have been enough to help him come to terms with the contradiction of his situation. We can never know if his suicidal inclinations were caused or exacerbated by what he had to do as one of Metternich’s agents. We might guess, though, that he was aware that people referred to Count Metternich as Mitternacht (midnight) and that he would have had some sympathy with those who experienced the dreaded knock on the door as the tolling of the midnight bell.

Thus, the chimes of midnight ringing from the campanile of San Marco invite the gondola rider (and the readers of Mayrhofer’s poem) to reflect on the powers that might still imprison or shackle us and the promise of escape (both on the open sea and as we are lulled to sleep). The waves and the sounds combine to rock us peacefully into a state of slumber which will allow us to escape (if only for a few hours) from the agonising reality that normally controls our waking lives.

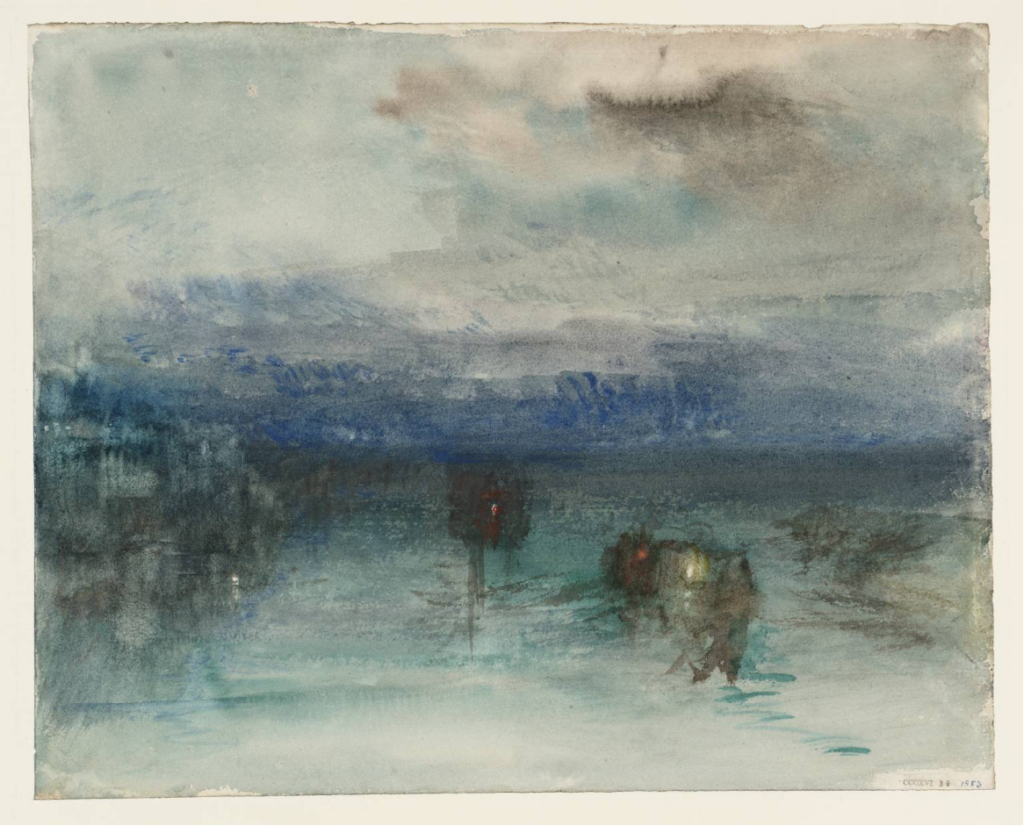

Joseph Mallord William Turner

London, Tate

[1] On 6th March 1824 Moritz von Schwind wrote to Franz von Schober about Schubert’s recent work following his illness:

“Schubert is pretty well already. He says that after a few days of the new treatment he felt how his complaint broke up and everything was different. He still lives one day on panada and the next on cutlets, and lavishly drinks tea, goes bathing a good deal besides and is superhumanly industrious. A new Quartet is to be performed at Schuppanzigh’s, who is quite enthusiastic and is said to have rehearsed particularly well. He has now long been at work on an Octet, with the greatest zeal. If you go to see him during the day, he says, “Hullo, how are you? – Good!” and goes on writing, whereupon you depart. Of Müller’s poems he has set two very beautifully, and three by Mayrhofer, whose poems have already appeared, ‘Boating’ [‘Gondelfahrt’ (sic)]; ‘Evening Star’ [‘Abendstern’] and ‘Victory’ [‘Sieg’].”

O. E. Deutsch, English translation by Eric Blom, Schubert. A Documentary Biography London 1946 p. 331

☙

Original Spelling Gondelfahrer Es tanzen Mond und Sterne Den flücht'gen Geisterreih'n: Wer wird von Erdensorgen Befangen immer seyn! Du kannst in Mondesstrahlen Nun, meine Barke, wallen; Und aller Schranken los, Wiegt dich des Meeres Schooß. Vom Markusthurme tönte Der Spruch der Mitternacht: Sie schlummern friedlich Alle, Und nur der Schiffer wacht.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 112.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 112 [126 von 212] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ177450902