An old Scottish ballad

(Poet's title: Eine altschottische Ballade)

Set by Schubert:

D 923

[September 1827]

Dein Schwert, wie ist’s vom Blut so rot,

Eduard, Eduard!

Dein Schwert, wie is’ts von Blut so rot

Und gehst so traurig da, oh!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Geier tot,

Mutter, Mutter!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Geier tot,

Und das, das geht mir nah, oh!

Deines Geiers Blut ist nicht so rot,

Eduard, Eduard!

Deines Geiers Blut ist nicht so rot,

Mein Sohn, bekenn mir frei, oh!

Ich hab geschlagen mein Rotross tot,

Mutter, Mutter!

Ich hab geschlagen mein Rotross tot,

Und es war so stolz und treu. Oh!

Dein Ross war alt und hast’s nicht not,

Eduard, Eduard!

Dein Ross war alt und hast’s nicht not,

Dich drückt ein andrer Schmerz, oh!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Vater tot,

Mutter, Mutter!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Vater tot,

Und das, das quält mein Herz! Oh!

Und was wirst du nun an dir tun

Eduard, Eduard!

Und was wirst du nun an dir tun,

Mein Sohn, bekenn mir mehr, oh!

Auf Erden soll mein Fuß nicht ruhn,

Mutter, Mutter!

Auf Erden soll mein Fuß nicht ruhn,

Will wandern über Meer. Oh!

Und was soll werden dein Hof und Hall,

Eduard, Eduard!

Und was soll werden dein Hof und Hall,

So herrlich sonst und schön, oh!

Ach, immer steh’s und sink und fall,

Mutter, Mutter!

Ach, immer steh’s und sink und fall,

Ich werd es nimmer sehn. Oh!

Und was soll werden dein Weib und Kind,

Eduard, Eduard!

Und was soll werden dein Weib und Kind,

Wenn du gehst über Meer, oh!

Die Welt ist groß, lass sie betteln drin,

Mutter, Mutter!

Die Welt ist groß! lass sie betteln drin,

Ich seh sie nimmermehr. Oh!

Und was soll deine Mutter tun,

Eduard, Eduard!

Und was soll deine Mutter tun,

Mein Sohn, das sage mir, oh!

Der Fluch der Hölle soll auf euch ruhn,

Mutter, Mutter!

Der Fluch der Hölle soll auf euch ruhn,

Denn ihr, ihr rietet’s mir, oh!

Your sword, why is it covered in blood so red?

Edward, Edward?

Your sword, why is it covered in blood so red

And why do you look so sad! Oh!

I have struck and killed my bird of prey

Mother, mother!

I have struck and killed my bird of prey,

And that has affected me! Oh!

Your bird of prey’s blood is not so red!

Edward, Edward!

Your bird of prey’s blood is not so red,

My son, confess it to me freely! Oh!

I have struck and killed my red horse!

Mother, mother!

I have struck and killed my red horse!

And it was so proud and faithful!

Your horse was old and you had no need!

Edward, Edward!

Your horse was old and you had no need

A different pain is pressing on you. Oh!

I have struck and killed my father,

Mother, mother!

I have struck and killed my father,

And that, that has disturbed my heart! Oh!

And what will you do with yourself now?

Edward, Edward!

And what will you do with yourself now?

My son, confess more to me! Oh!

My foot will not rest on earth!

Mother, mother!

My foot will not rest on earth!

I shall travel over the sea! Oh!

And what will become of your court and hall,

Edward, Edward,

And what will become of your court and hall,

Once so noble and beautiful! Oh!

Alas! Let it just stand and sink and fall,

Mother, mother!

Alas! Let it just stand and sink and fall,

I shall never see it! Oh!

And what will become of your wife and child,

Edward, Edward?

And what will become of your wife and child,

If you go over the sea – Oh!

The world is large! Let them beg in it,

Mother, mother,

The world is large! Let them beg in it,

I shall never see them again! Oh!

And what should your mother do?

Edward, Edward?

And what should your mother do?

My son, tell me that! Oh!

Let the curse of Hell settle on you,

Mother, mother!

Let the curse of Hell settle on you,

Since it was you, you who advised me to do it! Oh.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Birds Blood Curses Father and child Hell Horses Mother and child Red and purple Swords and daggers Walking and wandering

In the 1760’s and 1770’s it was still common practice for upper class men in northern Europe to look to Greece and Rome for their cultural identity. The universities limited their canon of set texts to the ancient languages and young aristocrats from England went on the Grand Tour to Italy in order to be exposed directly to the relics of classical civilisation. Showing an interest in different ‘relics’, as Bishop Thomas Percy did when he published ‘Reliques of Ancient English Poetry’ in 1765, therefore suggested that a reaction was underway. A counter-culture, which would value the products of people educated in different ways, with different stories and songs, challenged some of the assumptions about cultural hierarchies. It was also part of the political rebalancing that was taking place with the declining power of France and French (Latinate) taste, and the relative rise of Britain and Prussia.

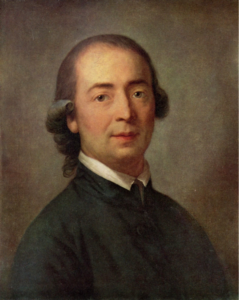

J. G. Herder was careful to argue, though, that in his work he was not advocating a rejigging of the hierarchy (with German speaking culture rising at the expense of French). Rather he was challenging the basic hierarchical assumption that some cultures are more valuable than others. To him, the point about collecting examples of popular ballads from ‘marginal’ areas (Scotland, Scandinavia, Ukraine etc.) was that they opened up specific and individual new insights into universal human experience. We see some of this approach in the passage where he introduces his translation of ‘An old Scottish ballad’ in his ‘Correspondence about Ossian and the songs of ancient peoples’:

Auszug aus einem Briefwechſel uͤber Oſſian und die Lieder alter Voͤlker. Ein andres lapplaͤndiſches Liebeslied an ſein Rennthier wollte ich Jhnen auch mittheilen; aber es iſt verworfen, und wer mag Zettel ſu- chen? Dafuͤr ſtehe hier ein altes, recht ſchau- derhaftes Schottiſches Lied, fuͤr das ich ſchon mehr ſtehen kann, weil ichs unmittelbar aus der Urſprache habe. Es iſt ein Geſpraͤch zwi- ſchen Mutter und Sohn, und ſoll im Schotti- ſchen mit der ruͤhrendſten Landmelodie beglei- tet ſeyn, der der Text ſo viel Raum goͤnnet: Dein Schwerdt, wie iſts von Blut ſo roth? Edward, Edward! . . . Koͤnnte der Brudermord Kains in einem Po- pulaͤrliede mit grauſendern Zuͤgen geſchildert werden? und welche Wuͤrkung muß im leben- digen Rhytmus das Lied thun? und ſo, wie viele viele Lieder des Volks! * * * * * Extract from a Correspondence about Ossian and the Songs of ancient peoples. I wanted to share with you another Lapplander love song addressed to a racing animal, but it got thrown away and who can be expected to look through the waste paper? Instead I am placing here an old, truly disturbing Scottish song, which I can use to represent much more, since I have it directly from the original language. It is a dialogue between mother and son, and it must have been accompanied in Scottish with the most stirring national melody, to which the song allows so much scope: Your sword, why is it covered in blood so red? Edward, Edward? . . . Could Cain's murder of his brother be presented in a popular song with terrifying features? and what effect would the song make with a lively rhythm? and this will be the case with so, so many songs of the people!

An old Scottish song about parricide is being used here instead of a Lapplander’s love song to his racing animal (reindeer? dog?) to typify the power of popular culture to address universal themes about human existence. Such ‘songs of the people’ can have incantatory power through their use of repetition, rhythm and climax. They can deal with the most extreme examples of human behaviour, including fratricide (starting with Cain and Abel). It is not just the Greeks with their stories of Oedipus, or the Romans and their manipulative matriarchs (such as Agrippina), who were able to create ‘disturbing’ poetry about parricide and incest.

Herder’s German text of the old Scottish ballad was based on the English version that appeared in Percy’s “Reliques of Ancient English Poetry” (1765), reproduced here in the original spelling:

EDWARD, EDWARD,

A SCOTTISH BALLAD,

From a MS. copy transmitted from Scotland.

Quhy dois zour brand sae drap wi' bluid,

Edward, Edward?

Quhy dois zour brand sae drap wi' bluid?

And quhy sae sad gang zee, O?

O, I hae killed my hauke sae guid,

Mither, mither;

O, I hae killed my hauke sae guid:

And I had nae mair bot hee, O.

Zour haukis bluid was nevir sae reid;

Edward, Edward.

Zour haukis bluid was nevir sae reid;

My deir son I tell thee, O.

O, I hae killed my reid-roan steid,

Mither, mither:

O, I hae killed my reid-roan steid,

That erst was sae fair and frie, O.

Zour steid was auld, and ze hae gat mair,

Edward, Edward:

Zour steid was auld, and ze hae gat mair,

Sum other dule ze drie, O.

O, I hae killed my fadir deir,

Mither, mither:

O, I hae killed my fadir deir

Alas! and wae is mee, O!

And quhatten penance wul ze drie for that?

Edward, Edward.

And quhatten penance will ze drie for that?

My deir son, now tell me, O.

Ile set my feit in zonder boat,

Mither, mither:

Ile set my feit in zonder boat,

And Ile fare ovir the sea, O.

And quhat wul zu doe wi' zour towirs and zour ha',

Edward, Edward?

And quhat wul ze doe wi' zour towirs and zour ha',

That were sae fair to see, O?

Ile let thame stand tul they doun fa',

Mither, mither:

Ile let thame stand tul they doun fa',

For here nevir mair maun I bee, O.

And quhat wul ze leive to zour bairns and zour wife,

Edward, Edward?

And quhat wul zu leive to zour bairns and zour wife,

Quhan zu gang ovir the sea, O?

The warldis room, late them beg thrae life,

Mither, mither:

The warldis room, let them beg thrae life,

For thame nevir mair wul I see, O.

And quhat wul ze leive to zour ain mither deir,

Edward, Edward:

And quhat wul ze leive to zour ain mither deir,

My deir son, now tell mee, O.

The curse of hell frae me sall ze beir,

Mither, mither:

The curse of hell frae me sall ze beir,

Sic counseils ze gave to me, O.

This curious song was transmitted to the Editor by Sir David Dalrymple, Bart., late Lord Hanes.

Herder, like all of the early collectors of folksong and folk poetry, had difficulties establishing a reliable methodology and he was not able to take a fully critical approach to his sources at times. In this case he had to rely on Percy’s ‘Reliques’, but it is now known that Percy added many more recent ballads to the folio of ancient texts which he claimed to have found lying abandoned in a house in Shropshire.

Of the Scottish ballads Percy includes, 'Edward, Edward' is the most gruesome. Percy identifies it as 'From a MS. copy transmitted from Scotland', given to him by David Dalrymple, Lord Hailes, who contributed many Scottish ballads to the Reliques, but he fails to recognise - at least in the text - that the ballad was very likely a recent composition rather than an ancient one. The evidence for this is twofold: first, the composition of the ballad is uncommonly sophisticated, and its orthography appears antique to the point of affectation. 'Quhatten', for example, is unheard of in Scots poetry since the twelfth century and appears to be a needlessly elaborate re-rendering of the Scots word 'quhat' (what). Secondly, the name 'Edward' is an anatopism in Scottish balladry, and apart from this example appears only when denoting an English king and almost never when naming another character in the wider ballad canon. From Frank Ferguson and Danni Glover, 'Scottish revenants: Caledonian fatality in Thomas Percy's Reliques' in William Hughes and Andrew Smith ed., Suicide and the Gothic Manchester University Press 2019

Whether any of this ultimately affects Herder’s argument that the ‘Edward, Edward’ ballad is an example of the ability of popular culture to express universal themes in a powerful way is doubtful, though.

Human beings in general seem to relish murder stories. The satisfaction and the pleasure we derive from them is usually related to the way in which the narrator carefully controls the release of information. We specifically do not want it all at once. We definitely do not want to start at the beginning and follow the chronological sequence. We want to be the detective who starts with the dead body and has to reconstruct the sequence of events, with the standard ingredients of victim, motive, suspects, perpetrator, twist at the end.

We begin in this case with the smoking gun, or rather the dripping sword, undisputably the murder weapon. So, who was the victim? We know it cannot have been the hawk and the red horse must be a red herring. Ah ha, he has murdered his father. But the twist is that this is not the twist. Much more interesting revelations are to come. We learn about Edward’s willingness to face the consequences of the murder. He will have to go into exile and abandon his castle and his dependents. He seems to have few qualms about leaving his wife and children to beg in the streets, but just when we think that this is showing us something about his cruelty and lack of feeling we learn that it might well be the opposite. He has been numbed and traumatised by the deed, since it turns out that he was not the primary perpetrator after all. He has allowed himself to be used by his terrible mother. We can therefore make a good guess at Edward’s motive, but we are left with no clues about his mother’s. Revenge? Ambition? Passion? There is something gloriously satisfying for the reader / listener about being left with such a significant mystery still to be solved.

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text

Eine altschottische Ballade

Dein Schwerdt, wie ists von Blut so roth?

Eduard1, Eduard!

Dein Schwerdt, wie ists von Blut so roth

Und gehst so traurig da! - O!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Geyer todt

Mutter, Mutter!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Geyer todt,

Und das, das geht mir nah! - O!

Deines Geyers Blut ist nicht so roth!

Eduard, Eduard!

Deines Geyers Blut ist nicht so roth,

Mein Sohn, bekenn mir frey! - O!

Ich hab geschlagen mein Rothroß todt!

Mutter, Mutter!

Ich hab geschlagen mein Rotroß todt!

Und es war so stolz und treu! O!

Dein Roß war alt und hasts nicht noth!

Eduard, Eduard,

Dein Roß war alt und hasts nicht noth,

Dich drückt ein andrer Schmerz. O!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Vater todt,

Mutter, Mutter!

Ich hab geschlagen meinen Vater todt,

Und das, das quält mein Herz! O!

Und was wirst du nun an dir thun?

Eduard, Eduard!

Und was wirst du nun an dir thun?

Mein Sohn, bekenn mir mehr! O!

Auf Erden soll mein Fuß nicht ruhn!

Mutter, Mutter!

Auf Erden soll mein Fuß nicht ruhn!

Will wandern über Meer! O!

Und was soll werden dein Hof und Hall,

Eduard, Eduard,

Und was soll werden dein Hof und Hall,

So herrlich sonst und schön! O!

Ach! immer stehs und sink' und fall,

Mutter, Mutter!

Ach immer stehs und sink' und fall,

Ich werd es nimmer sehn! O!

Und was soll werden dein Weib und Kind,

Eduard, Eduard?

Und was soll werden dein Weib und Kind,

Wenn2 du gehst über Meer - O!

Die Welt ist groß! laß sie betteln drinn,

Mutter, Mutter!

Die Welt ist groß! laß sie betteln drinn,

Ich seh sie nimmermehr! - O!

Und was soll deine Mutter thun?

Eduard, Eduard!

Und was soll deine Mutter thun?

Mein Sohn, das sage mir! O!

Der Fluch der Hölle soll auf Euch ruhn,

Mutter, Mutter!

Der Fluch der Hölle soll auf Euch ruhn,

Denn ihr, ihr riethet es mir! O.

1 Schubert consistently changed Herder's 'Edward' to 'Eduard', presumably to ensure that singers avoided using the German pronunciation of 'w' as /v/.

2 Schubert changed 'Wann' (When) to 'Wenn' (If)

Confirmed with Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry: consisting of Old Heroic Ballads, Songs, and other Pieces of our earlier Poets, (Chiefly of the Lyric kind.) Together with some few of later Date. Volume the First. London: Printed for J. Dodsley in Pall-Mall. M DCC LXV [1765], pages 53-56.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Johann Gottfried Herder’s Von Deutscher Art und Kunst. Einige fliegende Blätter. Hamburg, 1773. Bey Bode, pages 25-27.

Note: This is the first version of Herder’s translation of the old Scottish ballad Edward, Edward which he found in Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry.

Note: Schubert’s setting exists in three versions. Version 3 is phrased as a duet (in the last stanza). In addition, it substitutes “weh!” for each “O!”, and replaces “Geyer” by “Falke” in stanzas 1 and 2.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 25 [29 von 190] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ163283900