The god and the dancing girl. Indian legend

(Poet's title: Der Gott und die Bajadere. Indische Legende)

Set by Schubert:

D 254

[August 18, 1815]

Part of Goethe: The second collection intended for Goethe

Mahadöh, der Herr der Erde,

Kommt herab zum sechsten Mal,

Dass er unsers gleichen werde,

Mit zu fühlen Freud und Qual.

Er bequemt sich hier zu wohnen,

Lässt sich alles selbst geschehn.

Soll er strafen oder schonen,

Muss er Menschen menschlich sehn.

Und hat er die Stadt sich als Wandrer betrachtet,

Die Großen belauert, auf Kleine geachtet,

Verlässt er sie abends, um weiter zu gehn.

Als er nun hinaus gegangen,

Wo die letzten Häuser sind,

Sieht er, mit gemalten Wangen,

Ein verlornes, schönes Kind.

Grüß dich, Jungfrau! – Dank der Ehre!

Wart, ich komme gleich hinaus –

Und wer bist du? – Bajadere,

Und dies ist der Liebe Haus.

Sie rührt sich, die Zimbeln zum Tanze zu schlagen;

Sie weiß sich so lieblich im Kreise zu tragen,

Sie neigt sich und biegt sich und reicht ihm den Strauß.

Schmeichelnd zieht sie ihn zur Schwelle,

Lebhaft ihn ins Haus hinein.

Schöner Fremdling, lampenhelle

Soll sogleich die Hütte sein.

Bist du müd, ich will dich laben,

Lindern deiner Füße Schmerz.

Was du willst, das sollst du haben,

Ruhe, Freuden oder Scherz.

Sie lindert geschäftig geheuchelte Leiden.

Der Göttliche lächelt; er siehet mit Freuden,

Durch tiefes Verderben ein menschliches Herz.

Und er fordert Sklavendienste;

Immer heitrer wird sie nur,

Und des Mädchens frühe Künste

Werden nach und nach Natur.

Und so stellet auf die Blüte

Bald und bald die Frucht sich ein;

Ist Gehorsam im Gemüte,

Wird nicht fern die Liebe sein.

Aber, sie schärfer und schärfer zu prüfen,

Wählet der Kenner der Höhen und Tiefen

Lust und Entsetzen und grimmige Pein.

Und er küsst die bunten Wangen,

Und sie fühlt der Liebe Qual,

Und das Mädchen steht gefangen,

Und sie weint zum ersten Mal;

Sinkt zu seinen Füßen nieder,

Nicht um Wollust noch Gewinnst,

Ach! und die gelenken Glieder,

Sie versagen allen Dienst.

Und so zu des Lagers vergnüglicher Feier

Bereiten den dunklen, behaglichen Schleier

Die nächtlichen Stunden das schöne Gespinst.

Spät entschlummert unter Scherzen,

Früh erwacht nach kurzer Rast,

Findet sie an ihrem Herzen

Todt den vielgeliebten Gast.

Schreiend stürzt sie auf ihn nieder;

Aber nicht erweckt sie ihn,

Und man trägt die starren Glieder

Bald zur Flammengrube hin.

Sie höret die Priester, die Totengesänge,

Sie raset und rennet und theilet die Menge.

Wer bist du? was drängt zu der Grube dich hin?

Bei der Bahre stürzt sie nieder,

Ihr Geschrei durchdringt die Luft:

Meinen Gatten will ich wieder!

Und ich such ihn in der Gruft.

Soll zu Asche mir zerfallen

Dieser Glieder Götterpracht?

Mein! er war es, mein vor allen!

Ach, nur Eine süße Nacht!

Es singen die Priester: Wir tragen die Alten,

Nach langem Ermatten und spätem Erkalten,

Wir tragen die Jugend, noch eh sie’s gedacht.

Höre deiner Priester Lehre:

Dieser war dein Gatte nicht.

Lebst du doch als Bajadere,

Und so hast du keine Pflicht.

Nur dem Körper folgt der Schatten

In das stille Totenreich;

Nur die Gattin folgt dem Gatten:

Das ist Pflicht und Ruhm zugleich.

Ertöne, Trommete, zu heiliger Klage!

O nehmet, ihr Götter! die Zierde der Tage,

O nehmet den Jüngling in Flammen zu euch.

So das Chor, das ohn’ Erbarmen

Mehret ihres Herzens Not;

Und mit ausgestreckten Armen

Springt sie in den heißen Tod.

Doch der Götterjüngling hebet

Aus der Flamme sich empor,

Und in seinen Armen schwebet

Die Geliebte mit hervor.

Es freut sich die Gottheit der reuigen Sünder;

Unsterbliche heben verlorene Kinder

Mit feurigen Armen zum Himmel empor.

Mahadöh, the Lord of the earth,

Comes down for the sixth time,

So that he can become like us,

And feel joy and pain along with us.

He has resolved to live here,

Opening himself up to whatever happens;

Whether he has to punish or forgive,

He has to be human with humans.

And having observed the town as a traveller

Looking at the great and taking notice of the small,

He leaves it in the evening in order to go further.

Now that he has gone out

Where the last houses are,

He sees, with painted cheeks,

A lost, beautiful child:

Hello to you, miss! – Thank you for your courtesy!

Wait, I’ll come out straight away –

And who are you? – A bayadère

And this is the house of love.

She sets about preparing to hit the cymbals for the dance;

She knows how to hold herself so attractively as she turns around,

She bends, she twists and reaches out to hand him the garland.

With flattery she draws him to the threshold,

With liveliness she gets him into the house.

Beautiful foreigner, bright lamps

Will quickly light up this hut.

If you are tired, I will refresh you,

I will soothe any aches in your feet.

Whatever you want you shall have,

Calm, joy or fun.

She sets about soothing the simulated pains.

The divine one smiles; with joy he sees

A human heart through deep degradation.

And he demands the services of a slave;

This makes her all the more cheerful,

And the girl’s early arts

Gradually turn into nature.

And so following on from the blossom

The fruit appears increasingly quickly;

If there is an inclination to obedience

Love will not be far behind.

But, in order to test her more and more sharply,

He who knows the heights and the depths selects

Pleasure and horror and extreme pain.

And he kisses the bright cheeks,

And she feels the agony of love,

And the girl finds herself caught,

And she cries for the first time;

She sinks down to his feet,

Not motivated by sensuality or profit,

Oh! and those supple limbs,

They renounce all service.

And so the pleasurable celebration of the couch

Is prepared; a dark, comfortable veil

Of beautiful gossamer falls with the hours of night.

Having fallen asleep late because of the fun,

And having woken early after a short rest,

On her heart she finds

Her greatly beloved guest is dead.

Crying out she rushes around, up and down,

But she does not manage to wake him,

And the rigid limbs are carried

Quickly towards the funeral pyre.

She can hear the priests, the songs for the dead,

She is in a frenzy, running around, cutting through the crowd.

Who are you? Why are you being drawn to your tomb?

She bends down next to the bier,

Her cry rings through the air:

I want my husband back!

And I shall look for him in the tomb.

Am I expected to see them decay into dust

These limbs with their divine splendour?

Mine! He was mine, mine more than any other!

Oh, only one sweet night!

The priests sing: We carry the old

After long, tiring years and those who have caught a late cold,

We carry the young, even earlier than they think.

Listen to the doctrine of your priests:

This was not your husband.

For you live as a bayadère

And thus there is no obligation on you.

Only shadows follow the corpse

Into the quiet kingdom of the dead;

Only brides follow husbands:

That is both obligation and glory in one.

Ring out, trumpets, in a holy lament!

O gods, take the adornment of his days,

Take the young man in flames to yourself!

In this way, the chorus mercilessly

Increases the distress of her heart;

And with arms outstretched

She leaps into a hot death.

But the god / young man rises

Up out of the flames,

And floating into his arms

His beloved joins him.

Divinity rejoices in sinners who repent;

Lost children rise up immortal

Towards heaven with fiery arms.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Arms and embracing Bending Cheeks Circles Cymbals Dancing Dust Evening and the setting sun Feet Fire Flowers Flying, soaring and gliding Frenzy and lack of control Fruit Graves and burials Hearts Heaven, the sky Husband and wife Huts Joy Kissing Laments, elegies and mourning Leaping and jumping Limbs Night and the moon Pain Pictures and paintings Slaves and slavery Sweetness Tears and crying Towns Trumpets Veils Waking up Walking and wandering Wreaths and garlands

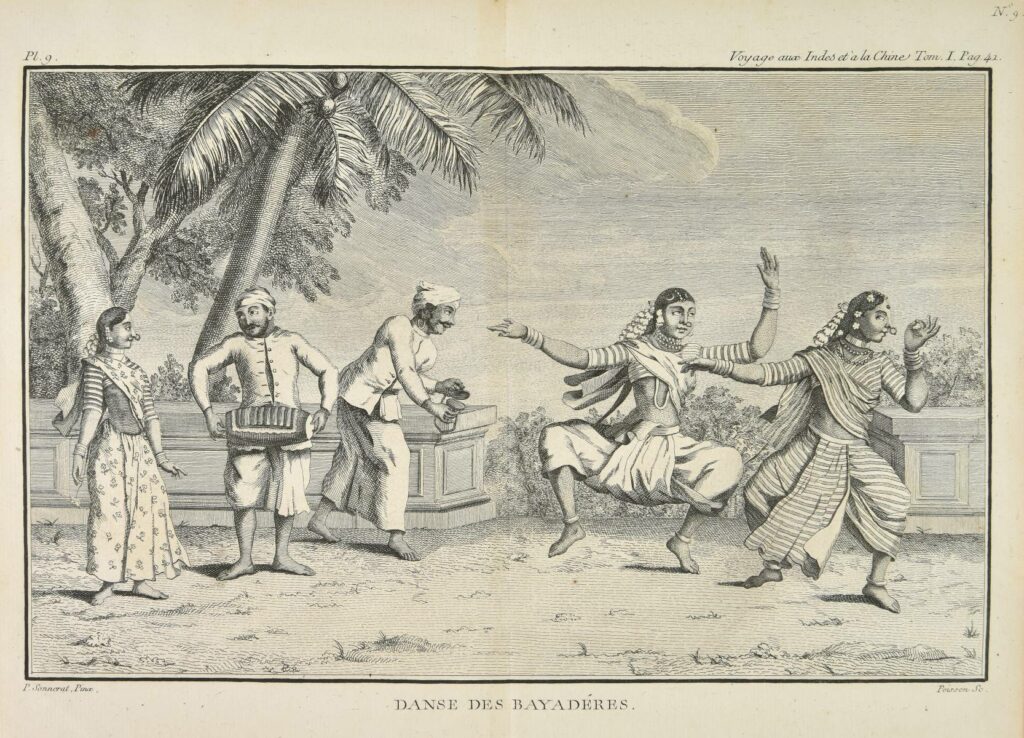

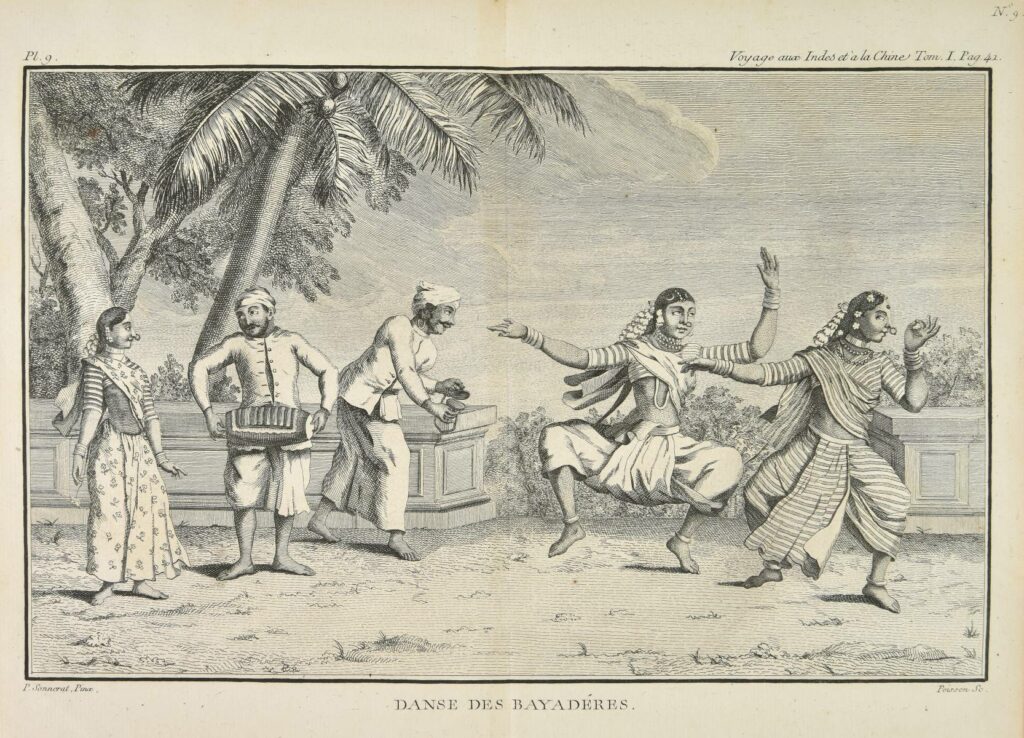

“Surat is famous for its Bayadères, whose correct name is Devadasi, the name Bayadères which we give them comes from the Portuguese word Bailladeras, which means Dancers. They are devoted to honouring the gods, which they follow in processions, dancing and singing before their images. A worker normally directs his youngest daughter to this role and sends her to the temple before she can bear children. They give them music and dance masters. The Brahmins cultivate their youth, whose first fruits they take to themselves; they end up as public women. They therefore form their own association and join up with musicians to go and dance for and amuse those who call for them. They dance and sing to the sound of the tal and the matalan, which drives them and regulates their beat and their steps. . . . The movement of their eyes, which they half close while bending over casually and softening their voices, proclaims the greatest voluptuousness. Various men behind them sing the refrain of each verse in chorus.”

(Pierre Sonnerat, Voyage aux Indes Orientales et à la Chine 1782, Vol. 1 Chapter 4 On Surat pp. 40 – 41, English translation by Malcolm Wren)

Sonnerat’s account of the customs of India was Goethe’s prime source for this ballad, first published in Schiller’s Musen-Almanach for 1798. Sonnerat’s text was more than a travelogue: he was concerned to understand the social structures and cultural phenomena of the lands he had visited, and Goethe responded in kind by creating a narrative that attempted to help the reader share the assumptions of a Hindu worldview.

Mahadöh (Mahadeva) is one of the names of Shiva, the creative destroyer and Lord of the Dance. In Goethe’s story his avatar is that of a young man who can both observe and interact with human concerns. It is not particularly clear whether he is genuinely experiencing mortal joy and pain in this incarnation or whether the simulated suffering that elicits the girl’s love is a pretence that cannot affect him deeply. However, one of the features of Hinduism is that it has not taken such seeming contradictions or tensions as a cause for doctrinal disputation or dogma in an attempt to create some sort of logical consistency (as happened in the early church, where Docetism, the idea that the incarnate Jesus could not ‘really’ have suffered but only appeared to do so, was condemned as heretical after intense debates and mutual anathematising). It is a paradox rather than a contradiction that Shiva is both destroyer and creator, both dancer and he who is danced for.

The unnamed dancing girl is presented as being ‘saved’ in some way through her encounter with the god. Like all of us in this turning world, she finds herself in a condition of degradation and relentless empty activity. The priests (her pimps, in effect) insist that there is no escape, but she finds a way to break out of the cycle. Her dance involves bending and circling, embodying the twists and turns of human existence. Her flexible limbs do their usual service, but touched by true love in her encounter with the visiting god her arms and legs stop operating. She sinks at her guest’s feet, renouncing all desire. By the morning the young visitor’s limbs are stiff and lifeless; she insists that she cannot bear the idea of witnessing the decomposition of these magnificent arms and legs (she may have some intuition that they are the source of her own dancing) and so she will perform suttee. She will escape the turning cycle and enter the flames that will liberate her.

‘Suttee’ (or ‘sati’) had long been a controversial practice. Mughal emperors had attempted to ban it, and colonial powers took measures to outlaw it in the 18th century (e.g. the French did so in Pondicherry, and the British issued a decree against it in Calcutta / Kolkota in 1798, the very year when Goethe’s poem was first published). Goethe is more concerned with understanding what motivates the practice rather than with any outraged condemnation of a culturally alien tradition. The dancing girl is presented as having total control over her decision; she is no oppressed widow being forced to commit agonising suicide against her will. Quite the reverse – she has to argue against the priests and the powers-that-be and insist on her right to perform what she knows to be her obligation. Her liberation comes from her acceptance of her subjugation. As explained in the fourth stanza, the prostitute was able to experience true love by taking on and relishing the role of a slave. The more lowly the service she was asked to perform the happier she became. Her guest recognised that she was someone who could take and pass the ultimate test. He offered her the supreme reward by dying in her arms and inviting her to throw herself onto his funeral pyre.

Goethe ends with a Western moralising conclusion: God welcomes back sinners who repent and ‘fallen’ women can achieve immortality through loving self-sacrifice. There is no real attempt here to understand the practice of suttee as the widow’s desire to fuse with Parvati, Shiva’s faithful consort, but nor does the idea of ‘heaven’ necessarily preclude such a view of the nature of ‘liberation’. Throughout the poem Goethe is more interested in what western and eastern religious traditions have in common than in what separates them. There is an incarnate god (Mahadöh / Jesus) who is concerned to share mortal pain in order to help bring about salvation. He travels around paying attention to all social classes, but taking particular note of the poor (‘publicans and sinners’). A devoted prostitute (the dancing girl / Mary Magdalene) falls at his feet before his atoning death. Dogmatic priests (Pharisees and Brahmins, but also Catholic and Protestant clergy in Goethe’s own world) fail to acknowledge the spiritual profundity and sincere devotion of excluded individuals. Religion can be antagonistic to true Englightenment.

Footnote for Wagnerians

Goethe’s ballad seems to underlie many of Wagner’s mature music-dramas. The wandering god visiting the earth to see how things are going is Wotan in Siegfried, and the Ring cycle ends with Brünhilde’s self-immolation on her lover’s funeral pyre. There is something of the visiting god too in the Flying Dutchman and the unnamed stranger in Lohengrin. The dancing girl becomes Kundry in Parsifal (she too pays particular attention to the redeemer’s feet!), and the final words of Parsifal (and of Wagner’s career) perhaps sum up much of what is going on in Der Gott und die Bajadere: ‘Erlösung den Erlöser’ (redemption for the redeemer).

☙

Original Spelling Der Gott und die Bajadere Indische Legende Mahadöh, der Herr der Erde, Kommt herab zum sechstenmal, Daß er unsers gleichen werde, Mit zu fühlen Freud´ und Qual. Er bequemt sich hier zu wohnen, Läßt sich Alles selbst geschehn. Soll er strafen oder schonen, Muß er Menschen menschlich sehn. Und hat er die Stadt sich als Wandrer betrachtet, Die Großen belauert, auf Kleine geachtet, Verläßt er sie Abends, um weiter zu gehn. Als er nun hinaus gegangen, Wo die letzten Häuser sind, Sieht er, mit gemalten Wangen Ein verlornes schönes Kind. Grüß dich, Jungfrau! - Dank der Ehre! Wart´, ich komme gleich hinaus - Und wer bist du? - Bajadere, Und dieß ist der Liebe Haus. Sie rührt sich, die Zimbeln zum Tanze zu schlagen; Sie weiß sich so lieblich im Kreise zu tragen, Sie neigt sich und biegt sich, und reicht ihm den Strauß. Schmeichelnd zieht sie ihn zur Schwelle, Lebhaft ihn ins Haus hinein. Schöner Fremdling, lampenhelle Soll sogleich die Hütte seyn. Bist du müd', ich will dich laben, Lindern deiner Füße Schmerz. Was du willst, das sollst du haben, Ruhe, Freuden oder Scherz. Sie lindert geschäftig geheuchelte Leiden. Der Göttliche lächelt; er siehet mit Freuden, Durch tiefes Verderben ein menschliches Herz. Und er fordert Sklavendienste; Immer heitrer wird sie nur, Und des Mädchens frühe Künste Werden nach und nach Natur. Und so stellet auf die Blüte Bald und bald die Frucht sich ein; Ist Gehorsam im Gemüthe, Wird nicht fern die Liebe seyn. Aber, sie schärfer und schärfer zu prüfen, Wählet der Kenner der Höhen und Tiefen Lust und Entsetzen und grimmige Pein. Und er küßt die bunten Wangen, Und sie fühlt der Liebe Qual, Und das Mädchen steht gefangen, Und sie weint zum erstenmal; Sinkt zu seinen Füßen nieder, Nicht um Wollust noch Gewinnst, Ach! und die gelenken Glieder, Sie versagen allen Dienst. Und so zu des Lagers vergnüglicher Feyer Bereiten den dunklen behaglichen Schleier Die nächtlichen Stunden, das schöne Gespinst. Spät entschlummert unter Scherzen, Früh erwacht nach kurzer Rast, Findet sie an ihrem Herzen Todt den vielgeliebten Gast. Schreiend stürzt sie auf ihn nieder, Aber nicht erweckt sie ihn, Und man trägt die starren Glieder Bald zur Flammengrube hin. Sie höret die Priester, die Todtengesänge, Sie raset und rennet und theilet die Menge. Wer bist du? was drängt zu der Grube dich hin? Bei der Bahre stürzt sie nieder, Ihr Geschrei durchdringt die Luft: Meinen Gatten will ich wieder! Und ich such ihn in der Gruft. Soll zu Asche mir zerfallen Dieser Glieder Götterpracht? Mein! er war es, mein vor allen! Ach, nur Eine süße Nacht! Es singen die Priester: Wir tragen die Alten, Nach langem Ermatten und spätem Erkalten, Wir tragen die Jugend, noch eh sie's gedacht. Höre deiner Priester Lehre: Dieser war dein Gatte nicht. Lebst du doch als Bajadere, Und so hast du keine Pflicht. Nur dem Körper folgt der Schatten In das stille Todtenreich; Nur die Gattin folgt dem Gatten: Das ist Pflicht und Ruhm zugleich. Ertöne, Trommete, zu heiliger Klage! O nehmet, ihr Götter! die Zierde der Tage, O nehmet den Jüngling in Flammen zu euch! So das Chor, das ohn' Erbarmen Mehret ihres Herzens Noth; Und mit ausgestreckten Armen Springt sie in den heißen Tod. Doch der Götter-Jüngling hebet Aus der Flamme sich empor, Und in seinen Armen schwebet Die Geliebte mit hervor. Es freut sich die Gottheit der reuigen Sünder; Unsterbliche heben verlorene Kinder Mit feurigen Armen zum Himmel empor.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Goethe’s sämmtliche Schriften. Siebenter Band. / Gedichte von Goethe. Erster Theil. Lyrische Gedichte. Wien, 1810. Verlegt bey Anton Strauß. In Commission bey Geistinger, pages 328-331; with Goethe’s Werke, Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand, Erster Band, Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, 1827, pages 251-255; and with Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1798, herausgegeben von Schiller. Tübingen, in der J.G.Cottaischen Buchhandlung, pages 188-193.

Goethe wrote the ballad between 6th and 9th June, 1797

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 328 [342 von 418] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ163965701