Mignon

(Poet's title: Mignon)

Set by Schubert:

D 321

[October 23, 1815]

Part of Goethe: The second collection intended for Goethe Goethe: Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre

Kennst du das Land, wo die Citronen blühn,

Im dunkeln Laub die Goldorangen glühn,

Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht,

Die Myrte still und hoch der Lorbeer steht?

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin, dahin

Möcht ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn!

Kennst du das Haus? Auf Säulen ruht sein Dach,

Es glänzt der Saal, es schimmert das Gemach,

Und Marmor-Bilder stehn und sehn mich an,

Was hat man dir, du armes Kind, getan?

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin, dahin

Möcht ich mit dir, o mein Beschützer, ziehn!

Kennst du den Berg und seinen Wolkensteg?

Das Maultier sucht im Nebel seinen Weg,

In Höhlen wohnt der Drachen alte Brut,

Es stürzt der Fels und über ihn die Flut?

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin, dahin

Geht unser Weg, o Vater, lass uns ziehn!

Do you know the country where the lemon trees blossom,

Where the golden oranges glow in the dark foliage,

Where a gentle wind wafts from the blue sky,

Where myrtles stand quietly and laurel trees stand tall,

Do you really know it?

Let us go there! There

Is where I would like to go off with you, my beloved.

Do you know the house? Its roof rests on columns,

The hall is glowing, the chamber is shining,

Marble images stand there and are looking at me:

What have they done to you, poor child?

Do you really know it?

Let us go there! There

Is where I would like to go off with you, my protector.

Do you know the mountain and its path into the clouds?

In the mist the mule is trying to find its way;

The dragon’s old brood lives in caves;

The cliff falls away and above it there is a waterfall.

Do you really know it?

Let us go there! There

Is where our route takes us. O father, let us go off!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Blue Buildings and architecture Caves Climbing Clouds Columns Dragons Floods and tides Flowers Fruit Gold Heaven, the sky Houses Italy Journeys Laurel Leaves and foliage Lemons Longing and yearning Marble Mist and fog Mountains and cliffs Myrtle North and south Paths Pictures and paintings Rivers – waterfalls, rapids and whirlpools Wind

Book 3 Chapter 1 of ‘Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre’ opens as follows:

Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn,

Im dunkeln Laub die Gold-Orangen glühn,

Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht,

Die Myrte still und hoch der Lorbeer steht?

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin! dahin

Möcht ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn.

Kennst du das Haus? Auf Säulen ruht sein Dach.

Es glänzt der Saal, es schimmert das Gemach,

Und Marmorbilder stehn und sehn mich an:

Was hat man dir, du armes Kind, getan?

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin! dahin

Möcht ich mit dir, o mein Beschützer, ziehn.

Kennst du den Berg und seinen Wolkensteg?

Das Maultier sucht im Nebel seinen Weg;

In Höhlen wohnt der Drachen alte Brut;

Es stürzt der Fels und über ihn die Flut!

Kennst du ihn wohl?

Dahin! dahin

Geht unser Weg! O Vater, laß uns ziehn!

Als Wilhelm des Morgens sich nach Mignon im Hause umsah, fand er sie nicht, hörte aber, daß sie früh mit Melina ausgegangen sei, welcher sich, um die Garderobe und die übrigen Theatergerätschaften zu übernehmen, beizeiten aufgemacht hatte.

Nach Verlauf einiger Stunden hörte Wilhelm Musik vor seiner Türe. Er glaubte anfänglich, der Harfenspieler sei schon wieder zugegen; allein er unterschied bald die Töne einer Zither, und die Stimme, welche zu singen anfing, war Mignons Stimme. Wilhelm öffnete die Türe, das Kind trat herein und sang das Lied, das wir soeben aufgezeichnet haben.

Melodie und Ausdruck gefielen unserm Freunde besonders, ob er gleich die Worte nicht alle verstehen konnte. Er ließ sich die Strophen wiederholen und erklären, schrieb sie auf und überstzte sie ins Deutsche. Aber die Originalität der Wendungen konnte er nur von ferne nachahmen; die kindliche Unschuld des Ausdrucks verschwand, indem die gebrochene Sprache übereinstimmend und das Unzusammenhängende verbunden ward. Auch konnte der Reiz der Melodie mit nichts verglichen werden.

Sie fing jeden Vers feierlich und prächtig an, als ob sie auf etwas Sonderbares aufmerksam machen, als ob sie etwas Wichtiges vortragen wollte. Bei der dritten Zeile ward der Gesang dumpfer und düsterer; das "Kennst du es wohl?" drückte sie geheimnisvoll und bedächtig aus; in dem "Dahin! Dahin!" lag eine unwiderstehliche Sehnsucht, und ihr "Laß uns ziehn!" wußte sie bei jeder Wiederholung dergestalt zu modifizieren, daß es bald bittend und dringend, bald treibend und vielversprechend war.

Nachdem sie das Lied zum zweitenmal geendigt hatte, hielt sie einen Augenblick inne, sah Wilhelmen scharf an und fragte: "Kennst du das Land?" - "Es muß wohl Italien gemeint sein", versetzte Wilhelm; "woher hast du das Liedchen?" - "Italien!" sagte Mignon bedeutend, "gehst du nach Italien, so nimm mich mit, es friert mich hier." - "Bist du schon dort gewesen, liebe Kleine?" fragte Wilhelm. - Das Kind war still und nichts weiter aus ihm zu bringen.

In the morning, when William looked around the house for Mignon he did not find her, but he did hear that she had gone out early with Melina, who had set off at the crack of dawn to sort out the wardrobe and the rest of the theatrical equipment.

After a few hours had passed, Wilhelm heard music outside his door. His first thought was that the harp-player had already returned, but then he soon detected the sounds of a zither and the voice which started to sing was that of Mignon. Wilhelm opened the door, the child stepped in and sang the song which we have already sketched.

Our friend was particularly pleased with the melody and the expression, even though at that point he could not understand all the words. He got her to repeat and explain the strophes, he wrote them down and translated them into German. But the originality of the turns of phrase was something that he was only able to capture faintly; the childlike innocence of the expression vanished as soon as the corresponding broken language was linked with the seemingly incoherent phrases. Nor could the appeal of the melody be compared to anything else.

She began each verse solemnly and grandly, as if she wanted to draw attention to something very special, as if she wanted to convey something important. At the third line the song became more muffled and sombre. 'Do you really know it?' was pronounced with deliberation and with a tone full of mystery. In 'Let us go there! There!' there lay an irresistible longing, and she knew how to modify 'let us go off' with each repetition, to such an extent that it was sometimes begging and urgent, then suddenly forceful and full of promise.

After she had come to the end of the song for a second time she paused for a moment, looked at Wilhelm sharply and asked, 'Do you know that country?' - 'It must be Italy that is meant;' replied Wilhelm, 'where did you get the little song from?' - 'Italy!' said Mignon meaningfully, 'If you go to Italy, take me with you. I am freezing here.' - 'Have you already been there, little one?' asked Wilhelm. - The child was quiet and nothing more could be got out of her.

As Goethe’s novel proceeds Wilhelm gradually puts together some of Mignon’s back story and is eventually able to speculate about some of the trauma that precipitated this song of loss and longing. However, as is clear from his first attempts to capture the meaning of the text, there are inconsistencies and lacunae in her account. She is simultaneously hiding and recovering her past. As she retrieves part of it, she reinterprets it. There will be both over- and under-emphasis of some details. Some of the trauma may have been so serious that it can never be allowed back into consciousness at all; some of it may have been so disturbing that it will never be possible for her to escape it. The memory is so seared into consciousness that it can never be modified; each re-encounter will precipitate the whole of the emotional torment. She cannot move on. She has to go back.

Wilhelm eventually learns that Mignon’s parents were Augustin and Sperata, both younger siblings of an Italian Marquis. As in the Greek tragedies, the parents were not aware of the incest at the time of their affair. Mignon therefore grew up in total ignorance of her parentage. It appears that she was not even able to identify herself as an orphan or a bastard. This inability to fit in with an established role in society may have been connected with, or may simply have been experienced as an added difficulty to, her uncertainty about her gender identity.

When Wilhelm first meets Mignon (Book II, Chapter 4), a member of a group of acrobats and circus performers, he does not know if he is dealing with a boy or a girl (the long black hair is tied up), but eventually decides on the latter.

"What do you call yourself?" he asked. "They call me Mignon." "How old are you?" "Nobody has counted." "Who was your father?" "The great devil is dead."

Wilhelm decides that ‘she’ must be about 12 or 13 years old, but he knows from the beginning that this is someone unlike anyone else in his previous experience.

Mignon is what she ‘is called’ not what she ‘calls herself’. Her identity is created by those around her. It is not clear if the boyish clothing she wears is also something imposed on her by the circus troupe or whether she has chosen it to assert her masculinity. He may well be a boy. Ze may be non-binary. We cannot know and s/he was perhaps unclear about this too. At least in circus and theatrical companies it is expected that people will play roles, and such contexts are as safe a place as any in an otherwise hostile world for those who feel the need to experiment with playing different gender roles.

Yet it soon becomes apparent that Mignon had not ‘run off to join the circus’ in the traditional way that non-conformist and non-heteronormative young people have always done. Her performing was not self discovery or self assertion. S/he never had the chance to find her/himself in [role] play. Mignon was abducted and enslaved. This is the horror which underlies ‘Kennst du das Land?’

The only memories from before the act of violence which took her from Italy are still images, but in vivid colour: lemon blossom and glinting golden oranges, dark green foliage, bright blue sky, tall trees. This is the Garden of Eden, from which Mignon, like so many of us, has been expelled. It is calm, the only movement is a light breeze, everything IS. Nothing happens. We ourselves are absent; indeed there are no humans there at all.

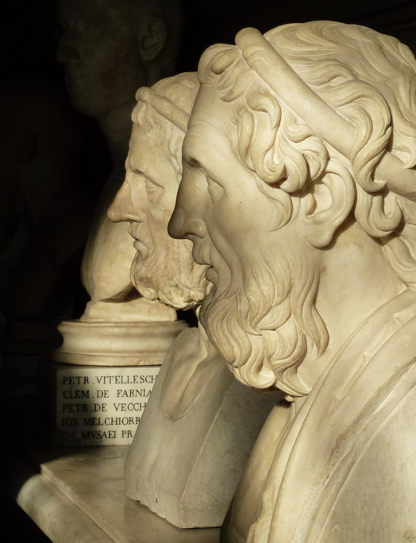

Strophe Two takes us from nature to the world of culture. Stone has been fashioned and polished to create columns and a roof, gleaming halls and shining pavements. This is the stage set for the moment of horror. In a terrifying flashback Mignon sees again the marble busts who impotently watch as she is carried off. ‘What have they done to you, poor kid?’, they ask. What HAVE they done? What have THEY done? What have they DONE?’

The flashbacks in strophe three take us up to the Alpine passes. We have left civilisation but the nature that we encounter here is not that of the calm, colourful garden. Now it is noisy and dramatic. Land and sky are strangely confused. Water (in the form of mist or flood) is to be feared. We are at the mercy of the strange animals who belong up here (dragons and mules). Cliffs fall away.

Kennst du den Berg und seinen Wolkensteg? Das Maultier sucht im Nebel seinen Weg

The journey that Mignon recalls was experienced as an act of violence. She had no agency and was unable to act or react. She was taken, abducted, enslaved. These things still happen and we have to remind ourselves of what is involved. The extent of the abuse probably explains some of the gaps in the narrative.

Yet in constructing the song, Mignon takes back control to some extent. She speaks of a longing to return; she is not just telling the story of her abduction. She evokes her vivid memories in order to urge Wilhelm to join her as she goes back. She of course wants to return to an untroubled garden, to an unchanging world of colour and calm, but this time with a lover. In stanza one she calls Wilhelm ‘o mein Geliebter’, even though she is aware that he is not in love with her (or at least is not erotically interested in him / her). She has realised that the untroubled garden from which she was abducted was not in fact perfect; she was never loved when she was there.

Similarly she is now prepared to return to the site of her abduction, to the house with its columns and roof, where nevertheless she was not safe. What she wants now is to go back there with a ‘protector’.

To get there she needs to cross that awful mountain pass again. This is the great obstacle. Is there a path? If there is, will we ever see it because of the fog? Won’t we fall or get attacked? It is so awful, so daunting, that she is determined to do it. We know, though, that for there to be any sort of healing, this is the only way. There are no short cuts, no tunnels. It is a climb. She knows that she cannot do it on her own. She needs a father.

So Wilhelm has become her lover, protector and father. These are the very people she has never had in her life, so we can be fairly certain that she is not relating to Wilhelm Meister as he is; he is a projection or, in psychoanalytical terms, this is a case of transference. She has used the idea of Wilhelm to allow her to embody all the absences and lacks that are so central to her experience of the world. What was lost has been found: all that is needed is a return to Italy, but this time with William, with a father, with a protector, with a lover.

As we listen to her song, on one level we are aware that she is deluded: William is not her father, protector or lover. There can be no going back. Yet we are also aware that she is singing of a journey we all need to take. Our journey here, to where we find ourselves now, was none of our doing. We all grow up aware that we are no longer in a world of safety and comfort. We have been thrown into a society that expects us to play roles we are not comfortable with or do jobs that we are incapable of. Like Mignon, we have a sense that there was a time when all went well, but the only way to get in touch with that world of fulfilment and colour is to cross a mountain range of obstacles. If we strive, we might be able do the journey in our way, taking the initiative, tracing a route through all the mist. If we do not decide to go back across the mountains we are accepting the fait accompli of our own abduction.

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text

Mignon

Kennst du das Land? wo die Citronen blühn,

Im dunkeln Laub die Gold-Orangen glühn,

Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht,

Die Myrte still und hoch der Lorbeer steht,

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin! Dahin

Möcht' ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn.

Kennst du das Haus? Auf Säulen ruht sein Dach,

Es glänzt der Saal, es schimmert das Gemach,

Und Marmorbilder stehn und sehn mich an:

Was hat man Dir, du armes Kind, gethan?

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin! Dahin

Möcht' ich mit dir, o mein Beschützer, ziehn.

Kennst du den Berg und seinen Wolkensteg?

Das Maulthier sucht im Nebel seinen Weg;

In Höhlen1 wohnt der Drachen alte Brut;

Es stürzt der Fels und über ihn die Flut.

Kennst du es2 wohl?

Dahin! Dahin

Geht unser Weg! O Vater, laß uns ziehn!

1 Schubert only knew this text from Beethoven's setting of it. Schubert therefore wrote this word as 'Höllen' (hell) not 'Hölen' (caves).

2 Schubert changed 'ihn' ('it' referring back to the mountain, the path or the cliff) to 'es' ('it', possibly referring back to the mule, but more likely to the whole idea of Italy, simply repeating 'es' from the previous two stanzas).

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Goethe’s Werke, Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand, Erster Band, Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cottaschen Buchhandlung, 1827, page 177. First published in Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre. Ein Roman. Herausgegeben von Goethe. Zweyter Band. Frankfurt und Leipzig. 1795, pages 7-8. The poem appears in Book 3, Chapter 1 of Goethe’s novel.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 7 [13 von 390] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ165619607

Thomas Carlyle’s English translation of Wilhelm Meister is available here: http://www.bartleby.com/ebook/adobe/314.pdf

The photos on this page were taken by Malcolm Wren in Italy and Slovenia