The lament of Ceres

(Poet's title: Klage der Ceres)

Set by Schubert:

D 323

[9th November 1815 to June 1816]

Ist der holde Lenz erschienen?

Hat die Erde sich verjüngt?

Die besonnten Hügel grünen,

Und des Eises Rinde springt.

Aus der Ströme blauem Spiegel

Lacht der unbewölkte Zeus,

Milder wehen Zephyrs Flügel,

Augen treibt das junge Reis.

In dem Hain erwachen Lieder,

Und die Oreade spricht:

Deine Blumen kehren wieder,

Deine Tochter kehret nicht.

Ach, wie lang’ ist’s, dass ich walle,

Suchend durch der Erde Flur,

Titan, deiner Strahlen alle

Sandt’ ich nach der teuren Spur,

Keiner hat mir noch verkündet

Von dem lieben Angesicht,

Und der Tag, der alles findet,

Die Verlorne fand er nicht.

Hast du Zeus! sie mir entrissen,

Hat, von ihrem Reiz gerührt,

Zu des Orkus schwarzen Flüssen

Pluto sie hinab geführt?

Wer wird nach dem düstern Strande

Meines Grames Bote sein?

Ewig stößt der Kahn vom Lande,

Doch nur Schatten nimmt er ein.

Jedem sel’gen Aug verschlossen

Bleibt das nächtliche Gefild,

Und so lang der Styx geflossen,

Trug er kein lebendig Bild.

Nieder führen tausend Steige,

Keiner führt zum Tag zurück,

Ihre Träne bringt kein Zeuge

Vor der bangen Mutter Blick.

Mütter, die aus Pyrrhas Stamme

Sterbliche, geboren sind,

Dürfen durch des Grabes Flamme

Folgen dem geliebten Kind;

Nur was Jovis Haus bewohnet,

Nahet nicht dem dunkeln Strand,

Nur die Seligen verschonet,

Parzen, eure strenge Hand.

Stürzt mich in die Nacht der Nächte

Aus des Himmels goldnem Saal,

Ehret nicht der Göttin Rechte,

Ach sie sind der Mutter Qual.

Wo sie mit dem finstern Gatten

Freudlos thronet, stieg ich hin,

Und träte mit den leisen Schatten

Leise vor die Herrscherin.

Ach, ihr Auge, feucht von Zähren,

Sucht umsonst das goldne Licht,

Irret nach entfernten Sphären,

Auf die Mutter fällt es nicht,

Bis die Freude sie entdecket,

Bis sich Brust mit Brust vereint

Und zum Mitgefühl erwecket,

Selbst der raue Orkus weint.

Eitler Wunsch, verlorne Klagen!

Ruhig in dem gleichen Gleis

Rollt des Tages sichrer Wagen,

Ewig steht der Schluss des Zeus.

Weg von jenen Finsternissen

Wandt’ er sein beglücktes Haupt,

Einmal in die Nacht gerissen,

Bleibt sie ewig mir geraubt,

Bis des dunkeln Stromes Welle

Von Aurorens Farben glüht,

Iris mitten durch die Hölle

Ihren schönen Bogen zieht.

Ist mir nichts von ihr geblieben,

Nicht ein süß erinnernd Pfand,

Dass die Fernen sich noch lieben,

Keine Spur von ihrer Hand?

Knüpfet sich kein Liebesknoten

Zwischen Kind und Mutter an?

Zwischen Lebenden und Toten

Ist kein Bündnis aufgetan?

Nein! nicht ganz ist sie entflohn,

Wir sind nicht ganz getrennt!

Haben uns die ewig Hohen

Eine Sprache doch vergönnt!

Wenn des Frühlings Kinder sterben,

Wenn von Nordes kaltem Hauch

Blatt und Blume sich entfärben,

Traurig steht der nackte Strauch,

Nehm ich mir das höchste Leben

Aus Vertumnus reichem Horn,

Opfernd es dem Styx zu geben,

Mir des Saamens goldnes Korn.

Traurernd senk’ ich’s in die Erde,

Leg es an des Kindes Herz,

Dass es eine Sprache werde

Meiner Liebe, meinem Schmerz.

Führt der gleiche Tanz der Horen

Freudig nun den Lenz zurück,

Wird das Tote neu geboren

Von der Sonne Lebensblick,

Keime, die dem Auge starben

In der Erde kaltem Schoß,

In das heitre Reich der Farben

Ringen sie sich freudig los.

Wenn der Stamm zum Himmel eilt,

Sucht die Wurzel scheu die Nacht.

Gleich in ihre Pflege teilt

Sich des Styx, des Äthers Macht.

Halb berühren sie der Toten,

Halb der Lebenden Gebiet,

Ach sie sind mir teure Boten

Süße Stimmen vom Cozyt!

Hält er gleich sie selbst verschlossen

In dem schauervollen Schlund,

Aus des Frühlings jungen Sprossen

Redet mir der holde Mund,

Dass auch fern vom goldnen Tage,

Wo die Schatten traurig ziehn,

Liebend noch der Busen schlage,

Zärtlich noch die Herzen glühn.

O so lasst euch froh begrüßen,

Kinder der verjüngten Au,

Euer Kelch soll überfließen

Von des Nektars reinstem Tau.

Tauchen will ich euch in Strahlen,

Mit der Iris schönstem Licht

Will ich eure Blätter malen

Gleich Aurorens Angesicht.

In des Lenzes heiterm Glanze

Lese jede zarte Brust,

In des Herbstes welkem Kranze

Meinen Schmerz und meine Lust.

Has beauteous spring appeared?

Has the earth rejuvenated itself?

The sunlit hills are becoming green

And the surface of the ice is cracking.

Out of the blue mirror of the streams

The cloudless Zeus is laughing,

Zephyrus’s wings are beating more gently,

The young sprigs are bursting with buds.

Songs are awakening in the grove,

And the Oread speaks:

Your flowers are returning,

Your daughter is not returning.

Oh, how long has it been that I have been pacing around

Searching through the fields of the Earth?

Titan, all your rays of light,

I have sent all your rays to track down the dear one;

Noone has as yet given me any news

Of her beloved face,

And the day which finds all things

Has not found the lost one.

Zeus, have you snatched her from me,

Stirred by her charm, has

Pluto taken her to the black river of Orcus?

Has Pluto abducted her?

Who will go to that gloomy bank

And be the messenger of my grief?

The boat is endlessly pushing off from the land

But it only ever takes on shadows.

Hidden away from all blessed eyes

Remains the nocturnal realm,

And for as long as the Styx has been flowing

It has never carried any living image.

A thousand steps lead down there,

But none lead back to daylight,

No witnesses come to give evidence of her tears

Before the anxious gaze of her mother.

Mothers who are descended from Pyrrha

Are born mortal,

They are allowed to go through the flames of the grave

To follow their beloved child;

Only those who inhabit Jove’s house

Cannot approach the dark shore,

Only the blessed ones are exempted,

Parcae, by your strict hand.

Throw me into the night of nights

Out of the golden hall of heaven,

Show no respect to my rights as a goddess,

Oh, my distress is that of a mother!

There, where with her dark spouse

She is joylessly enthroned, that is where I would like to climb down,

And with a light shadow I want to step

Gently before the Empress.

Oh, her eyes, wet with tears

Are searching in vain for the golden light,

They are wandering off to distant spheres,

But they do not fall on her mother –

Until joy uncovers her,

Until breast is united with breast,

And, awakened to compassion,

Even the rough river Orcus weeps.

Pointless wish! Wasted laments!

Calmly along the same track

The secure chariot of day rolls on.

The decision of Zeus stands for ever.

Away from those darknesses

He has turned his lucky head;

Torn from me once during the night

She now remains stolen from me for ever,

Until the dark waves of the river

Glow with Aurora’s colours,

And until Iris appears in the middle of hell

Carrying her beautiful bow.

Is nothing of her left for me?

No sweet pledge left as a souvenir

Showing that she still loves me from afar,

No trace of her dear hand?

Are there no love bonds tying

The child up to her mother?

Between the living and the dead,

Has no connection been established?

No, she has not fled away completely!

We are not completely separated!

The eternal powers above have

In fact granted us a language!

When the children of spring die,

When, because of the cold breath of the north wind

Leaves and flowers lose their colour,

And the naked straw stands sadly,

Then I take the highest life

Out of Vertumnus’s rich horn of plenty,

Sacrificing it to offer it to the Styx,

What to me is the golden corn of the seed.

I lower it mournfully into the Earth

And lay it on the child’s heart,

So that it will become a language,

Expressing my love, my sorrow.

Only when the regular dance of the Hours leads

Spring joyfully back

Will the dead be born anew

Out of the living glance of the sun;

Seeds which to the eye appeared to have died

In the cold womb of the Earth,

In the cheerful realm of colour

They joyfully fight themselves free.

As stems hurry up towards the sky

The roots shyly search for the night,

Sharing equally in their care

Are the powers of the Styx and of the Ether.

They are in contact half with the dead

And half with the domain of the living –

Oh, they are my dear messengers,

Sweet voices of Cocytus.

Even though he is still holding her captive

In the dreadful abyss,

Out of the young shoots of spring

Her beauteous mouth is speaking to me;

Telling me that although far away from golden days

Where shadows fall sadly,

Her breast is still beating with love,

Hearts are still glowing affectionately.

Oh, therefore let me greet you with delight,

Children of the rejuvenated meadow,

Your cup will overflow

With nectar’s purest dew.

I shall bathe you all in rays;

With Iris’s most beautiful light

I shall paint your petals

To look like Aurora’s face.

In the cheerful gaze of spring

Let each tender breast take note,

In the withered garland of autumn let each breast take note of

My sorrow and my pleasure.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Autumn Black Blue Boats and ships Breaking and shattering Breath and breathing Buds By water – river banks Carts and chariots Chest / breast Cold Colour (general) Cups and goblets Dancing Daughters Dew The earth Eternity Ether Eyes Fading and losing colour Fields and meadows Fighting and wrestling Fire Fleeing Flowers Frost and ice Gazes, glimpses and glances Germination, shoots and sprouting Gold Graves and burials Green Hands Hearts Heaven, the sky High, low and deep Hills and mountains Horns Husband and wife Jupiter / Zeus Knots and bonds Messengers Laments, elegies and mourning Lap, womb (Schoß) Leaves and foliage Lethe Light Lost and found Mirrors and reflections Morning and morning songs Mother and child Near and far Nectar Night and the moon North and south Rainbows Rays of light Resurrection Rivers (Strom) Seeds Shade and shadows Songs (general) Spheres Spring (season) Stems and stalks Steps and staircases The sun Surface of the water Tears and crying Thrones The underworld (Orcus, Hades etc) Waves – Welle Wind Woods – groves and clumps of trees (Hain) Wreaths and garlands Youth

Who’s who?

| Names (Latin / Greek) | |

| Ceres / Demeter | Goddess of agriculture and fertility |

| Jove / Zeus | God of the sky and thunder, king of the gods |

| Proserpina (Cora) / Persephone | Daughter of Ceres and Jove, abducted by Pluto |

| Zephyrus | God of the west wind. Married to Iris |

| the Oreads | Nymphs of the mountains (including Echo) |

| the Titans | Divine beings, overthrown by Jove / Zeus and the other gods of Olympus |

| Pluto / Hades | God of the underworld, brother of Ceres |

| Pyrrha | One of only two survivors of the great deluge, after which she had to repopulate the earth |

| the Parcae | The three fates who control the string of destiny (similar to the Norse Norns) |

| Aurora | Goddess of dawn |

| Iris | The rainbow, and a messenger of the gods. Married to Zephyrus |

| Vertumnus | God of seasons and change |

| the Horae | Goddesses of the seasons and the hours |

Gazeteer

| Orcus | Another name for Hades, either the underworld itself, or its ruler Pluto |

| Styx | The river that forms the boundary between the Earth and the underworld |

| Cocytus | A river in the underworld, a tributary of the Acheron |

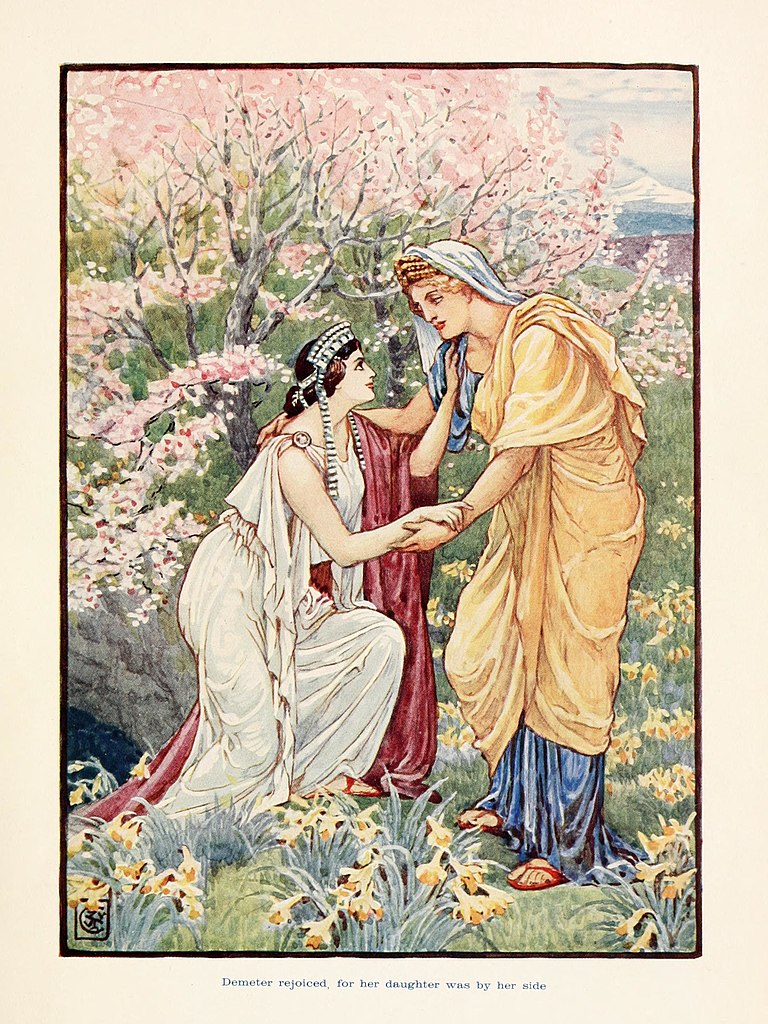

We ought to think about her every day when we eat our bread or cereals, for the Latin adjective ‘cerealis’ (the origin of the noun ‘cereal’) means ‘connected with Ceres, goddess of the production of grain’. The lament of Ceres expresses her frustration about the fact that she is separated from her daughter, Persephone, goddess of spring and rejuvenation. Ceres as goddess of corn and seed produces her bounty at the beginning of autumn and the following year’s harvest is dependent on the sacrifice, death and burial of some of this year’s grain. Just as grain needs to be ground and killed so that we can make nourishing bread, so it can only produce new life next spring if it dies and is buried at the end of the year.

This central mystery of agriculture is embodied in the myth of Ceres and Persephone. A number of versions of the story were told in the ancient world (e.g. The Homeric Hymns II[1], Ovid’s Metaphorphoses V[2], oral reports at the Eleusynian Festivals that are no longer accessible directly), but the basic idea is that the beautiful Persephone was carried off while picking spring flowers and taken down to be the consort of the ruler of the underworld. The distraught Ceres wandered far and could find no trace of her daughter, but was eventually told that Jove (Persephone’s father and Pluto’s brother) had agreed that Persephone should stay in the underworld for part of every year, but that she could return to Earth each spring. Her annual return and reunion with her mother underlie the phenomenon of germination, whereby the dead seeds of the previous year sprout into life. The stem rushes up towards the sky (the realm of Jove), but the roots shyly and slowly grow back into the soil towards the underworld (Pluto is Zeus’s brother). Both earth (terroir) and heaven (the weather) have vital roles (‘divine’ roles in this mythology) to play in the process of agriculture.

What was Schiller’s motivation in writing about this myth? We tend to think of him as a figure of the enlightenment, so it is rather surprising to see him choosing an aspect of ancient Greek culture which seems to be so ‘irrational’. Although Schiller did not share all of Goethe’s detailed interest in science (particularly geology, mineralogy, botany and metereology, all of which are basic to the Persephone myth), he did know enough to be able to explain how it was that the seasons changed without recourse to religious or mythological explanations. What was still a mystery, of course, was the secret of the buried seed. How does it know when and how to germinate? He would have talked to Goethe about the latter’s theories about developmental biology (he had published An Attempt to Explain the Metamorphosis of Plants in 1790), but without an understanding (or even the concept) of genetics natural philosophers of the late 18th century were unable to shed any light on the matter. It remained the domain of priests and mystics.

Schiller’s concern is therefore to try to get inside the myth, to see what wisdom led the ancients to interpret the world in their way. Rather than declaring that the Greeks had ‘primitive’ ideas that have now been superseded by later enlightenment (offered by either the church or scientists), he seems to be suggesting that we need to look sympathetically at the old stories and identify what they still have to offer us. This is the nature of his and of Goethe’s classicism: the Greeks and Romans do not offer us ‘models’ to follow so much as a way of thinking about the world that can inspire us to be newly creative.

Ceres and Persephone help us to think about creativity itself. On the material level, they represent aspects of fertility and motherhood, and allegorically they evoke artistic creativity and the production of poetry.

Ceres appears in the text primarily as a ‘mother’, and all mothers experience their relationship with their daughters as loss. On the most basic level, children do go off and leave their parents. In patriarchal societies daughters are indeed ‘carried off’ when they are married (traditionally this involved going to live with the new husband’s family, in another village); all too many are still abducted more literally. The more effort the mother puts into raising her daughter, the greater the loss when she goes. The experience of nurturing children is long and by the time the children are mature the mother has lost her own fertility. The golden ripeness (Ceres) comes at the expense of her verdant youth (Persephone).

None of this all too obvious explanation makes total sense of the extent of Ceres’s frustration, though. She is surely crying for more than her own lost youth or because her daughter is now living with an unsuitable man (albeit her brother, the girl’s uncle!). Her pain is connected primarily with the fact that there can be no communication between mother and daughter while Persephone is in the underworld. She has had no message from her, there are no witnesses to the tears that have been shed, Ceres cannot send a messenger and certainly (as a goddess) cannot go down to the underworld to talk to her. Yet, amazingly, there is a means of communication – ‘eine Sprache’ (a language). Some of her golden, mature corn has to be buried and killed. The new life that emerges will speak to Ceres of Persephone’s love, since the roots are going down to the daughter and the stem is growing up to the mother. They are in contact through the medium of death and regeneration.

Persephone never speaks in the course of the poem. She is not even named. However, by the end of the text ‘a language’ has been identified that allows the mother to be in contact with her hidden daughter. This offers hope to anyone who is in search of something precious that they have lost or that is inaccessible to them. For writers and other creators the bleakness and barrenness of the Earth in winter (while Persephone is in the underworld) is an allegory of writer’s block, when there is a total certainty that something is real and is ready to be expressed but there is no way of getting in touch with it. Very often things need to mature and be sacrificed before the sprouts of creativity begin to appear. The myth of Ceres will therefore continue to speak to us for as long as the mystery of creativity is unexplained.

[1] http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0138%3Ahymn%3D2

[2] http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0028%3Abook%3D5%3Acard%3D341

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text Klage der Ceres Ist der holde Lenz erschienen? Hat die Erde sich verjüngt? Die besonnten Hügel grünen, Und des Eises Rinde springt. Aus der Ströme blauem Spiegel Lacht der unbewölkte Zeus, Milder wehen Zephyrs Flügel, Augen treibt das junge Reis. In dem Hayn erwachen Lieder, Und die Oreade spricht: Deine Blumen kehren wieder, Deine Tochter kehret nicht. Ach, wie lang' ist's, daß ich walle Suchend durch der Erde Flur! Titan, deiner Strahlen alle Sandt' ich nach der theuren Spur, Keiner hat mir noch verkündet Von dem lieben Angesicht, Und der Tag, der alles findet, Die Verlorne fand er nicht. Hast du, Zeus! sie mir entrissen, Hat, von ihrem Reiz gerührt, Zu des Orkus schwarzen Flüssen Pluto sie hinabgeführt? Wer wird nach dem düstern Strande Meines Grames Bothe seyn? Ewig stößt der Kahn vom Lande, Doch nur Schatten nimmt er ein. Jedem sel'gen Aug' verschlossen Bleibt das nächtliche Gefild', Und so lang der Styx geflossen, Trug er kein lebendig Bild. Nieder führen tausend Steige, Keiner führt zum Tag zurück, Ihre Thräne bringt kein Zeuge Vor der bangen Mutter Blick. Mütter, die aus Pyrrhas Stamme Sterbliche gebohren sind, Dürfen durch des Grabes Flamme Folgen dem geliebten Kind, Nur was Jovis Haus bewohnet, Nahet nicht dem dunkeln Strand, Nur die Seligen verschonet, Parzen, eure strenge Hand. Stürzt mich in die Nacht der Nächte Aus des Himmels goldnem Saal, Ehret nicht der Göttinn Rechte, Ach! sie sind der Mutter Qual! Wo sie mit dem finstern Gatten Freudlos thronet, stieg ich hin, Und1 träte mit den leisen Schatten Leise vor die Herrscherinn. Ach ihr Auge, feucht von Zähren, Sucht umsonst das goldne Licht, Irret nach entfernten Sphären, Auf die Mutter fällt es nicht, Bis die Freude sie entdecket, Bis sich Brust mit Brust vereint, Und, zum Mitgefühl erwecket, Selbst der rauhe Orkus weint. Eitler Wunsch! Verlorne Klagen! Ruhig in dem gleichen Gleis Rollt des Tages sichrer Wagen, Ewig steht der Schluß des Zeus. Weg von jenen Finsternissen Wandt er sein beglücktes Haupt, Einmal in die Nacht gerissen, Bleibt sie ewig mir geraubt, Bis des dunkeln Stromes Welle Von Aurorens Farben glüht, Iris mitten durch die Hölle Ihren schönen Bogen zieht. Ist mir nichts von ihr geblieben, Nicht ein süß erinnernd Pfand, Daß die Fernen sich noch lieben, Keine Spur von ihrer Hand2? Knüpfet sich kein Liebesknoten Zwischen Kind und Mutter an? Zwischen Lebenden und Todten Ist kein Bündniß aufgethan? Nein, nicht ganz ist sie entflohen, Wir sind nicht ganz getrennt! Haben uns die ewig Hohen Eine Sprache doch vergönnt! Wenn des Frühlings Kinder sterben, Wenn von Nordes kaltem Hauch Blatt und Blume sich entfärben, Traurig steht der nackte Strauch, Nehm ich mir das höchste Leben Aus Vertumnus reichem Horn, Opfernd es dem Styx zu geben, Mir des Saamens goldnes Korn. Traurernd senk' ich's in die Erde, Leg' es an des Kindes Herz, Daß es eine Sprache werde Meiner Liebe, meinem Schmerz. Führt der gleiche Tanz der Horen Freudig nun den Lenz zurück, Wird das Todte neu gebohren Von der Sonne Lebensblick! Keime, die dem Auge starben In der Erde kaltem Schooß, In das heitre Reich der Farben Ringen sie sich freudig los. Wenn der Stamm zum Himmel eilt, Sucht die Wurzel scheu die Nacht, Gleich in ihre Pflege theilet Sich des Styx, des Aethers Macht. Halb berühren sie der Todten, Halb der Lebenden Gebiet, Ach sie sind mir theure Bothen Süße Stimmen vom Cocyt! Hält er gleich sie selbst verschlossen In dem schauervollen Schlund, Aus des Frühlings jungen Sprossen Redet mir der holde Mund, Daß auch fern vom goldnen Tage, Wo die Schatten traurig ziehn, Liebend noch der Busen schlage, Zärtlich noch die Herzen glühn. O, so laßt euch froh begrüßen, Kinder der verjüngten Au, Euer Kelch soll überfließen Von des Nektars reinstem Thau. Tauchen will ich euch in Strahlen, Mit der Iris schönstem Licht Will ich eure Blätter mahlen Gleich Aurorens Angesicht. In des Lenzes heiterm Glanze Lese jede zarte Brust, In des Herbstes welkem Kranze Meinen Schmerz und meine Lust. 1 Schubert added 'Und' (And) to the text 2 Schubert changed 'Keine Spur der theuren Hand' (no trace of the dear hand) to 'Keine Spur von ihrer Hand' (no trace of her hand)

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Friedrich von Schiller’s Gedichte. Zweyter Theil. Wien, 1816. Bey Chr. Kaulfuß und C. Armbruster. Gedruckt bey Anton Strauß. [Meisterwerke deutscher Dichter und Prosaisten. Vierzehntes Bändchen.] pages 62-67; with Gedichte von Friederich Schiller, Erster Theil, Leipzig, 1800, bey Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius, pages 5-11; and with Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1797, herausgegeben von Schiller. Tübingen, in der J.G.Cottaischen Buchhandlung, pages 34-41.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 62 [70 von 422] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ157692806