Fragment from Aeschylus

(Poet's title: Fragment aus dem Aeschylus)

Set by Schubert:

D 450

[June 1816]

So wird der Mann, der sonder Zwang

Gerecht ist, nicht unglücklich sein;

Versinken ganz in Elend kann er nimmer.

Indes der frevelnde Verbrecher

Im Strome der Zeit gewaltsam untergeht,

Wenn am zerschmetterten Maste

Das Wetter die Segel ergreift.

Er ruft, von keinem Ohr vernommen,

Kämpft in des Strudels Mitte, hoffnungslos.

Des Frevlers lacht die Gottheit nun,

Sieht ihn, nun nicht mehr stolz, in Banden

Der Not verstrickt, umsonst die Felsbank fliehn;

An der Vergeltung Fels scheitert sein Glück,

Und unbeweint versinkt er.

Thus the man who, without compulsion,

Is righteous will not be unhappy;

He can never sink totally into suffering.

Meanwhile the sinful criminal

Will violently drown in the stream of time

When the mast shatters

And the weather seizes the sail.

He calls out but no ear hears him,

He battles in the midst of the whirlpool, without hope.

Divinity now laughs at the sinner,

Seeing that he is no longer proud, tied up in the straps

Of necessity, trying in vain to escape from the rocky shore;

At the cliff of vengeance his luck runs out,

And he sinks unlamented.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Boats and ships Knots and bonds Laments, elegies and mourning Mountains and cliffs On the water – rowing and sailing Rivers (Strom) Rivers – waterfalls, rapids and whirlpools Storms Time Under the water, sinking and drowning

This fragment is one of a number of blood-curdling Odes declaimed by the Chorus in the final part of Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, three Athenian plays about the murder of Agamemnon by his wife Klytemnestra on his return from Troy and the repercussions of this deed. The plays were awarded the prize at the Dionysia festival in 458 BC and constitute the only complete trilogy to survive from ancient Greece.

Orestes (supported by Apollo) has appealed to Athene at her temple for judgement. He has admitted that he killed his mother (Klytemnestra), but this was to avenge her murder of his father, Agamemnon. The Chorus of Furies demand that matricide be punished appropriately, and while Athene is considering what to do the Chorus continue to expound on the consequences of Orestes not receiving what they see as a just punishment. These lines are spoken by the Furies (the Eumenidae) just before Athene, Apollo and Orestes return to the stage and the jury is invited to hear arguments on both sides.

ἑκὼν δ᾽ ἀνάγκας ἄτερ δίκαιος ὢν

οὐκ ἄνολβος ἔσται·

πανώλεθρος <δ᾽> οὔποτ᾽ ἂν γένοιτο.

τὸν ἀντίτολμον δέ φαμι παρβάταν

ἄγοντα πολλὰ παντόφυρτ᾽ ἄνευ δίκας

βιαίως ξὺν χρόνῳ καθήσειν

λαῖφος, ὅταν λάβῃ πόνος

θραυομένας κεραίας.

καλεῖ δ᾽ ἀκούοντας οὐδὲν <ἐν> μέσᾳ

δυσπαλεῖ τε δίνᾳ·

γελᾷ δὲ δαίμων ἐπ᾽ ἀνδρὶ θερμῷ,

τὸν οὔποτ᾽ αὐχοῦντ᾽ ἰδὼν ἀμαχάνοις

δύαις λαπαδνὸν οὐδ᾽ ὑπερθέοντ᾽ ἄκραν·

δι᾽ αἰῶνος δὲ τὸν πρὶν ὄλβον

ἕρματι προσβαλὼν δίκας

ὤλετ᾽ ἄκλαυτος, αἶστος.

Aeschylus, Eumenides 550-565

Whoever is just willingly and without compulsion

will not lack happiness;

he will never be utterly destroyed.

But I say that the man who boldly transgresses,

amassing a great heap unjustly—by force,

in time, he will strike his sail,

when trouble seizes him

as the yardarm is splintered.

He calls on those who hear nothing

and he struggles in the midst of the whirling waters.

The god laughs at the hot-headed man,

seeing him, who boasted that this would never happen,

exhausted by distress without remedy and unable to surmount the cresting wave.

He wrecks the happiness of his earlier life on the reef of Justice,

and he perishes unwept, unseen.

English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, 1926

We are therefore dealing with just a ‘fragment’ from Aeschylus, in that we are presented with only one side of the argument. We are offered a lyric rather than a drama. With the absence of competing voices or counter-arguments we are invited to contemplate a single thought: that crime must lead to suffering, with the unstated assumption that all suffering is a consequence of crime. As the criminal’s ship crumbles in the face of a storm, he hopelessly clings on to the shattered mast. He finds himself entwined in the rigging as he is pulled into the swirling waters and driven towards the rocks. Yet the gods can laugh at his fate, since none of this is their reponsibility; he has chosen to break the rules and this is what comes of it.

This is one way of trying to understand the human condition, and of resolving the so-called ‘problem of evil’ (why do good people suffer and bad people thrive?). From this perspective, the fact that we are suffering is evidence that we are not good. If we find that our life is a shipwreck, we need to accept responsibility for our actions. Orestes might claim that there were mitigating circumstances that justified the killing of his mother, but there can nevertheless be no avoiding the consequences of his action. Matricides must die. In this form of theodicy God or the gods, fate or circumstances beyond our control, none of these can or should be held responsible for our condition. If we are suffering, that must be our fault. This is the way of thinking which explains disease as a sort of punishment, and poverty as a result of fecklessness or laziness.

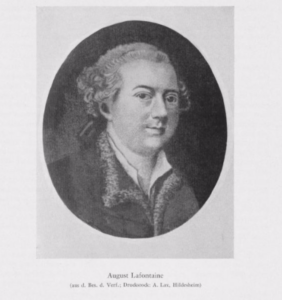

In 2019 Peter Rastl discovered that the German translation of this ‘fragment’ from Aeschylus (previously misattributed to Mayrhofer) was by August Lafontaine, and that Schubert’s probable source was Lafontaine’s Eugenie, der Sieg über die Liebe (Eugenie, the victory over love), written in 1813 (and published at the height of the Wars of Liberation in 1814). The third volume of this long family saga (although set in the previous generation) reflects the concerns of Lafontaine’s German speaking readers at the time of publication about resisting Napoleon and his armies.

Two brothers, Robert and Hermann, live with their friend the Baron. Hermann has a son, Günther, and the baron has a son and a daughter (Rudolph and Eugenie) of similar age. One day the adults wonder what they will do if the French invade. Should they all move to America or should they resist? They discuss the dangers of Saxons, Prussians and Austrians fighting each other, and decide that they ought to bring up their boys as primarily Germans, who are proud of what they have in common. They also decide that they should have a rigorous, physical upbringing, on the model of the Spartans. In addition to the exertions of swimming, climbing and hunting, their uncle Robert teaches the three children other values derived from the ancient Greeks:

Dann erzählte Robert die Beispiele der Treue, der Liebe, der Großmuth, der Aufopferung, alle die sanften Tugenden des häuslichen, des glücklichen Lebens des Frieden; oder er zeigte ihnen die Wunder der Natur, die ewigen Gesetze ihres wohltätigen Wirkens und der allgemein Liebe, die wie das Licht die ganze Natur durchströmt und umfängt.

Dann las er mit ihnen die Mythen der ersten Menschen, und redete von den Wohlthätern des Menschengeschlechtes, deren Namen, deren Ruhm die undankbaren Menschen vergessen, und deren Namen nur unter den Engeln glänzen: den viele bedeutenden Namen Prometheus, der den armen Menschen die Quelle aller Künste, das Feuer vom Himmel brachte, sie aus den dunkeln, unterirdischen, gegrabenen Wohnungen an das Licht, in die erste Hütte führte, der sie lehrte die Thiere, die Diener der menschlichen Arbeiten, zähmen, der ihnen die Sicherheit des frohen Lebens, den Samen der Ceres gab, und das edelste Geräth des Menschen, den Pflug. Dann erhob er den Blick der glücklichern Menschen gen Himmel, lehrte sie den Auf- und Untergang der Sterne, die Zeit, das Jahr zu bestimmen; dann lehrte er sie die Gottheit verehren und das Gesetz. Und endlich gab er ihnen, die zitternd das Grab sahen, den Siegeskranz des menschlichen Geschlechts, die unsterbliche Hoffnung, das göttlichste Geschenk der Sterblichen.

Dan sang Günther das erhabene Lied aus dem Aeschylus:

So wird der Mann, der sonder Zwang

Gerecht ist, nicht unglücklich seyn;

Versinken ganz in Elend kann er nimmer,

Indes der frevelnde Verbrecher

Im Strom der Zeit gewaltsam untersinkt,

Wenn am zerschmetterten Maste

Das Wetter die Segel ergreift.

Er ruft, von keinem Ohr vernommen,

Kämpft in des Strudels Mitte hoffnungslos.

Des Frevlers lacht die Gottheit jetzt,

Sieht ihn, nun nicht mehr stolz, in Banden

Der Noth verstrickt, umsonst die Felsbank fliehn;

An der Vergeltung Fels scheitert sein Glück

Und unbeweint versinkt er.

Diese Verse sang selbst der Baron leise mit, der sonst nie mitsang. "Natürlich!" sagte Robert - "denn das ist das ewige, allgemeine Gesetz der Sterblichen, das ewig festsheht."

"Ist´s die Vaterlandsliebe nicht, Robert?"

"Es ist nur ein einzelnes Gesetz; und darum ergreift jenes das Herz stärker."

Es war, als hätte die Natur den Kindern die drei Lehrer zur Bildung ihres Charakters bestimmt. Von dem Baron lernten sie Mässigung, Ordnung im Leben, Stätigkeit, Geduld, Ruhe und Achtung für den Anstand. Von Hermann bekamen sie den Eifer für das Recht, den Haß gegen die Unterdrückung, den Muth, alle Verhältnisse des Lebens mit Freimüthigkeit zu beurteilen, und sie zu zerreißen, wenns Noth thut, die hohe Liebe zur Unabhängigkeit, die Unerschrockenheit, allem, mit Kraft, auch dem Schicksale entgegenzutreten. Robert erhob sie über das Leben, über die Erde, über die Zeit in den Himmel, in eine andere, in eine schönere Welt. Er gab ihnen zum Trost für alle Opfer, die Hermann kühn von ihnen forderte, die Flügel der Poesie und die schönen Gefühle des Glücks jenseits.

* * * * *

Robert then narrated examples of fidelity, of love, of magnanimity, of self-sacrifice, all of the gentle virtues of happy, domestic, peaceful life; or he showed them the wonders of nature, the eternal laws of its charitable workings and of general love, which (like light) flows through and embraces the whole of nature.

Then he read with them the myths about the first humans, and spoke about the good deeds of the human race, whose names, whose fame thankless humans had forgotten, and whose names now only glowed amongst the angels: the very significant name of Prometheus, who brought to poor humans the source of all the arts, fire from heaven, taking them into the light out of the dark dwellings that they had dug underground, leading them to their first huts, where they learnt to tame animals to help with human work, who gave them the security of a happy life, the seed of Ceres, and the most noble tool of human beings - the plough. He then raised the eyes of happy humans towards heaven, taught them to determine the rise and fall of the stars, time and the calendar; he then taught them to honour divinity and the law. And finally, as they looked fearfully towards the grave, he gave them the victory wreath of the human race - immortal hope, the most divine gift to mortals.

Then Günther sang the sublime song from Aeschylus:

Thus the man who, without compulsion,

Is righteous will not be unhappy;

He can never sink totally into suffering.

Meanwhile the sinful criminal

Will violently drown in the stream of time

When the mast shatters

And the weather seizes the sail.

He calls out but no ear hears him,

He battles in the midst of the whirlpool, without hope.

Divinity now laughs at the sinner,

Seeing that he is no longer proud, tied up in the straps

Of necessity, trying in vain to escape from the rocky shore;

At the cliff of vengeance his luck runs out,

And he sinks unlamented.

The Baron himself joined in, quietly singing these verses, even though he otherwise never sang along. "Naturally!" said Robert, "since that is the eternal, general law of mortal beings that eternally holds true."

"Is that not love of the fatherland, Robert?"

"It is only a single law; and that is why the heart grasps it more firmly."

It was as if nature had selected these three teachers to develop the character of the children. From the Baron they learned moderation, self-control, restraint, patience, calm and respect for decency. From Hermann, they obtained their passion for justice, their hatred of oppression, the courage to make fair judgements in all their dealings in life and to stand aside when necessary, their noble love of independence, their determination to deal with anything, even fate itself, with strength. Robert raised them up above life, above the earth, beyond time, into heaven, into another, into a more beautiful world. To console them for all the sacrifice that Hermann boldly demanded of them, he gave them in return the wings of poetry and a beautiful feeling of happiness.

☙

Original Spelling Fragment aus dem Aeschylus So wird der Mann, der sonder Zwang Gerecht ist, nicht unglücklich seyn; Versinken ganz in Elend kann er nimmer, Indes der frevelnde Verbrecher Im Strome der Zeit gewaltsam untersinkt, Wenn am zerschmetterten Maste Das Wetter die Segel ergreift. Er ruft, von keinem Ohr vernommen, Kämpft in des Strudels Mitte, hoffnungslos. Des Frevlers lacht die Gottheit jetzt, Sieht ihn, nun nicht mehr stolz, in Banden Der Not verstrickt, umsonst die Felsbank fliehn; An der Vergeltung Fels scheitert sein Glück, Und unbeweint versinkt er.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Aeschylus with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph.D. Volume II. London: William Heinemann, NewYork: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. MCMXXVI [1926], page page 322 (verses 550-565); and with Aeschyli tragoediae edidit A. Kirchhoff. Berolini apud Weidmannos, MDCCCLXXX [1880], pages 260-261 (verses 540-555).

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Eugenie, der Sieg über die Liebe. von August Lafontaine. Dritter Band. Wien, 1814. In der Franz Haas’schen Buchhandlung, page 35.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 25 [31 von 244] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ168532203