Funeral song for a soldier

(Poet's title: Grablied auf einen Soldaten)

Set by Schubert:

D 454

Schubert did not set the stanzas in italics[July 1816]

Zieh hin, du braver Krieger du!

Wir g’leiten dich zur Grabesruh,

Und schreiten mit gesunkner Wehr

Von Wehmut schwer

Und stumm vor deinem Sarge her.

Du warst ein biedrer, deutscher Mann,

Hast immerhin so brav gethan.

Dein Herz, voll edler Tapferkeit

Hat nie im Streit

Geschoss und Säbelhieb gescheut.

Warst auch ein christlicher Soldat,

Der wenig sprach und vieles tat;

Dem Fürsten und dem Lande treu,

Und fromm dabei

Von Herzen, ohne Heuchelei.

Du standst in grauser Mitternacht,

In Frost und Hize auf der Wacht;

Ertrugst so standhaft manche Not

Und danktest Gott

Für Wasser und für’s liebe Brot.

Wie du gelebt, so starbst auch du!

Schloss’st deine Augen freudig zu

Und dachtest: “Aus ist nun der Streit

Und Kampf der Zeit,

Jezt kommt die ew’ge Seligkeit.”

Der liebe Herrgott kannte dich.

In Himmel kommst du sicherlich.

Du Wittwe und ihr Kinderlein,

Traut Gott allein:

Er wird nun eure Stüze sein.

Die Bahre poltert in die Gruft;

Wir aber donnern in die Luft

Dein leztes Lebewohl drei Mal.

Im Himmelssaal

Dort sehn wir dich ohn’ alle Qual.

Nehmt seinen Säbel von der Bahr

Und seid so brav, als wie er war.

Dann überwinden wir, wie er.

Und heiß und schwer

Drükt uns des Lebens Joch nicht mehr.

Trupp.

Eilt, Kameraden, von der Gruft!

Weil uns die Trommel wieder ruft.

Er rastet nun im kühlen Sand:

Uns fodert Fürst und Vaterland!

Wir bieten ihm

Mit Ungestüm

Die rauhe Kriegerhand.

Zwar ging es leichter in dem Feld

Als auf dem Bette aus der Welt.

Doch alles nur nach Gottes Rat!

So denkt ein redlicher Soldat.

Ihm geht es gut,

Er stirbt mit Mut,

Wie unser Kamerad.

Go off, you brave warrior!

We are accompanying you to your final resting place,

With downturned weapons we are marching,

Heavy with sadness,

We are silent before your coffin.

You were an upright German man,

You always behaved so honourably.

Your heart, full of noble courage,

In battle it never

Wavered in the face of gunfire or sword-thrusts.

You were also a Christian soldier,

Who said little but did a great deal;

Faithful to your Prince and your land,

With piety too

Coming from the heart, without any hypocrisy.

In the fearsome midst of the night you stood

Guard in frost and sweltering heat;

You so steadfastly bore various hardships

And you gave thanks to God

For water and for our beloved bread.

Just as you lived, you died in the same way!

You closed your eyes joyfully

And thought, “The struggle is now over,

Time’s battle;

Now comes eternal blessedness.”

Our beloved Lord God knew you.

You are definitely on the way to Heaven.

You widow and little child,

Trust God alone:

He is now going to be your support.

The bier is crashing into the sides of the grave

But we will raise thunder in the air

Giving three cheers as your last farewell.

In the hall of Heaven

We shall see you without any pain.

Take your sabre up to the bier

And be as brave as he was.

Then we shall overcome, as he did.

The heat and weight

Of life’s yoke will no longer press down on us.

Squad.

Rush, comrades, away from the grave!

For the drum is calling us again.

He is now resting in the cool sand:

We are claimed by our Prince and our Fatherland!

We offer him

Impetuously

Our rough warrior hands.

Indeed it is easier to go onto the battlefield

Than to go to bed away from the world.

But everything in accordance with God’s will!

That is how an honest soldier thinks.

It is fine with him,

He dies with courage

Like our comrade.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Bread Carrying a heavy burden Coffins Eternity Eyes Farewell and leave taking Father and child Frost and ice Germany and being German Graves and burials Guns Hearts Heat Heaven, the sky Husband and wife Joy Midnight Noise and silence Orphans Swords and daggers Thunder and lightning Time War, battles and fighting Weight – light and heavy Widows

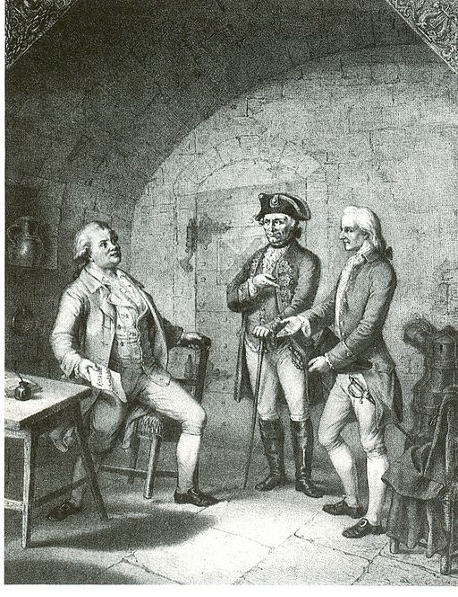

According to the poet’s son, who published an early edition of Schubart’s work, this ‘Todtenmarsch‘ (Funeral March) was written in response to an incident in autumn 1784. In 1777 Schubart had been arrested and imprisoned without trial in Hohenasperg (near Ludwigsburg, Schwabia). He was initially held in solitary confinement and for a number of years he was not allowed access to books or writing materials. As the years passed, he became a famous political prisoner (his ‘crime’ had been, in his capacity as editor of Die Deutsche Chronik, to criticise the arbitrary actions of Duke Karl Eugen of Württemburg), but his later comments suggest that the experience had broken him:

This sick state remained with me throughout the whole of the autumn, and each fading, falling leaf on the Linden tree that stood directly across from me reminded me of my death. Although death had already lost most of its terrors for me, I remained human and I could never think of it without a secret shudder. If our Commander Christ was able to say, 'Father deliver me from this hour!' (when, in the Garden of Gethsemene at night bloody sweat covered his forehead and he sank his head, experiencing deadly anxiety in the very depths of his soul), why should not his weaker disciples be expected to demonstrate a heroism in the face of death or refuse to acknowledge any fearlessness before its horrors, in a battle against human nature? - How melancholy sweet was the scene when I saw the corpse of a soldier being carried past me in a funeral march, with the sound of muffled drums behind the coffin; when the comrades of the one who was going home paraded behind him with serious expressions and with their weapons lowered and I heard the soldiers' final greeting (with clattering weapons) thundering in my ears. - "Oh, sleep well, you good warrior," I thought, "you are arriving in a land where no more bayonets are shining, where no sabres are whirring through the air, where no murderous bullets are flying, where no battle cries can be heard, somewhere where you will encounter no more tempests or snowstorms; it is somewhere where you will hear the spirit of peace murmuring above you, where you will be stationed to a post that means you will have forgotten all your cares, the anxiety resulting from your commander's rapier, your deprivations and your sad state of slavery." (From Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, Leben und Gesinnungen. Von ihm selbst im Kerker aufgesetzt Edited by Karl-Maria Guth, Berlin 2014 page 197 English translation by Malcolm Wren)

We need to bear this background in mind if we are tempted to read the resulting poem as in any way jingoistic. For Schubart, editor of ‘The German Chronicle’ (Ulm 1775 ff), being ‘German’ (deutsch) was about being down to earth and honest rather than about being gung-ho and domineering. The soldier who does his duty and supports his Prince is to be honoured; the Prince himself can be mocked, particularly if he does not live up to the standards of being a decent ‘German’. Schubart spent ten and a half years in Hohenasperg as a German prisoner of conscience.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHohenasperg_Detail_3_im_Abendlicht.jpg

☙

Original Spelling

Todtenmarsch

Zieh hin, du braver Krieger, du!

Wir gleiten dich zur Grabesruh,

Und schreiten mit gesunkner Wehr,

Von Wehmuth schwer

Und stumm vor deinem Sarge her.

Du warst ein biedrer, deutscher Mann,

Hast immerhin so brav gethan.

Dein Herz, voll edler Tapferkeit

Hat nie im Streit

Geschoß und Säbelhieb gescheut.

Warst auch ein christlicher Soldat,

Der wenig sprach - und vieles that;

Dem Fürsten und dem Lande treu,

Und fromm dabey

Von Herzen, ohne Heuchelei.

Du standst in grauser Mitternacht,

In Frost und Hize auf der Wacht;

Ertrugst so standhaft manche Noth

Und danktest Gott

Für Wasser, und für's liebe Brod.

Wie du gelebt, so starbst auch du!

Schloßst deine Augen freudig zu,

Und dachtest: "Aus ist nun der Streit

Und Kampf der Zeit,

Jezt kommt die ew'ge Seligkeit."

Der liebe Herrgott kannte dich.

In Himmel kommst du sicherlich.

Du Wittwe und ihr Kinderlein,

Traut Gott allein:

Er wird nun eure Stüze seyn.

Die Bahre poltert in die Gruft;

Wir aber donnern in die Luft

Dein leztes Lebewohl dreimal.

Im Himmelssaal

Dort sehn wir dich ohn' alle Qual.

Nehmt seinen Säbel von der Bahr,

Und seyd so brav, als wie er war.

Dann überwinden wir, wie er.

Und heiß und schwer

Drükt uns des Lebens Joch nicht mehr.

Trupp.

Eilt, Kameraden, von der Gruft!

Weil uns die Trommel wieder ruft.

Er rastet nun im kühlen Sand:

Uns fodert Fürst und Vaterland!

Wir bieten ihm

Mit Ungestüm

Die rauhe Kriegerhand.

Zwar gieng' es leichter in dem Feld

Als auf dem Bette aus der Welt.

Doch alles nur nach Gottes Rath!

So denkt ein redlicher Soldat.

Ihm geht es gut,

Er stirbt mit Muth,

Wie unser Kamerad.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Christ. Fridr. Daniel Schubart. Zweyter Theil. Neueste Auflage. Frankfurt 1803. Deutscher Parnaß. Die vollständigste, correcteste und wohlfeilste Ausgabe Deutscher Dichter des goldenen Zeitalters. In 84 Theilen. Wien, bey Bauer und Dirnböck. pages 242-244; with Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubarts sämtliche Gedichte. Von ihm selbst herausgegeben. Zweiter Band. Stuttgart, in der Buchdruckerei der Herzoglichen Hohen Carlsschule, 1786, pages 392-394; and with Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart’s Gedichte. Herausgegeben von seinem Sohne Ludwig Schubart. Zweyter Theil. Frankfurt am Main 1802, bey J. C. Hermann, pages 325-327.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 242 [250 von 302] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ204921004