Journey to Hades

(Poet's title: Fahrt zum Hades)

Set by Schubert:

D 526

[January 1817]

Der Nachen dröhnt, Zypressen flüstern,

Horch, Geister reden schaurig drein,

Bald werd ich am Gestad, dem düstern,

Weit von der schönen Erde sein.

Da leuchten Sonne nicht, noch Sterne,

Da tönt kein Lied, da ist kein Freund.

Empfang die letzte Träne, o Ferne!

Die dieses müde Auge weint.

Schon schau ich die blassen Danaiden,

Den fluchbeladnen Tantalus,

Es murmelt todesschwangern Frieden,

Vergessenheit, dein alter Fluss.

Vergessen nenn ich zwiefach Sterben.

Was ich mit höchster Kraft gewann,

Verlieren, wieder es erwerben!

Wann enden diese Qualen, wann?

The boat is creaking, cypress trees are whispering –

Listen, there are also spirits making bloodcurdling speeches;

I shall soon be on that dismal shore,

Where I shall be far away from the beautiful Earth.

Over there neither the sun nor the stars shed any light,

No song can be heard there, there is no friend there.

Distance, receive the last tear

That this tired eye will ever shed.

I can already behold the pale Danaids

And Tantalus, weighed down with curses;

Oblivion is murmuring a peace that is pregnant with death,

[Oblivion] – your ancient river Lethe.

I consider oblivion to be a double death:

What I obtained using the highest skill

Has to be lost – and it has to be re-acquired –

When are these torments going to end? When?

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

The ancient world Boats and ships By water – beaches and general Curses Cypress trees The earth Eyes Ferries Forgetting Friends Ghosts and spirits Hell Here and there Journeys Lethe Light Lost and found Near and far On the water – rowing and sailing Pain Rivers (Fluß) Sighs and sighing Songs (general) Stars The sun Tears and crying Tiredness The underworld (Orcus, Hades etc) Whispering

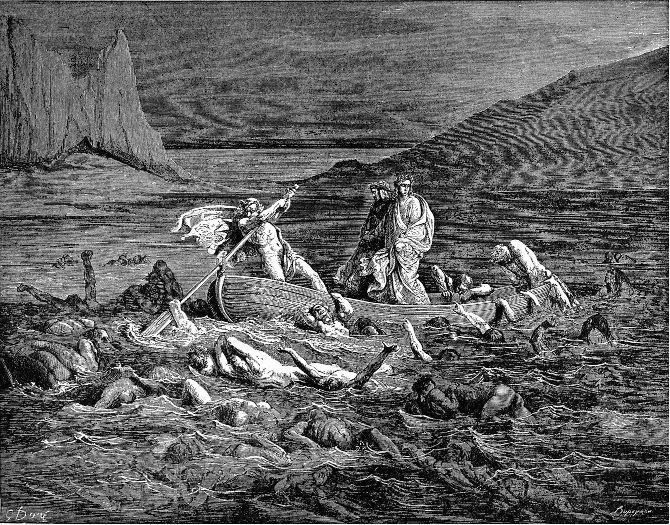

As in all the most effective horror films, it is more what we hear than what we see that creates the atmosphere. We are on a boat that is creaking or rumbling, ghostly voices are uttering bloodcurdling sounds and there is an eerie whooshing or an ominous whispering in the trees. Their distinctive outline might just be detectable in the murk, but the main reason why the speaker is aware that these are Cypress trees is that he knows where the ferryman is taking him: Cypresses are sacred to Pluto / Hades, the god of the underworld.

He is entering a world that is negative. It is lit by no sun and no stars. There are no songs and no friends. There are no more tears, not because there is no reason to cry but because the supply has been exhausted. This is the world of the River Lethe, oblivion itself, where we both forget and are forgotten. All that we have striven to achieve is wiped out, and we have to start all over again (as do the Danaids, who are condemned to carry jugs of water to fill a leaking tub or sieve). There can be no end to it.

The speaker is on a journey where the destination can never be reached. Perhaps it is not even a journey at all, since on the psychological level he is not going anywhere at all: he is already experiencing the torments of hell. The river Lethe will never obliterate the recurring agony.

☙

Classical Footnotes

The ferry to the Underworld

Mayrhofer would have assumed that his readers were familiar with the mythology of Charon, the elderly ferryman, who took the dead to Hades. Ancient Greeks used to place a coin on the tongue of the deceased to serve as the fare.

A ferryman of gruesome guise keeps ward Upon these waters,— Charon, foully garbed, With unkempt, thick gray beard upon his chin, And staring eyes of flame; a mantle coarse, All stained and knotted, from his shoulder falls, As with a pole he guides his craft, tends sail, And in the black boat ferries o'er his dead;— Old, but a god's old age looks fresh and strong. Virgil, Aeneid Book 6 298ff English translation by Theodor C. Williams

Cypresses

Cypress trees (Cupressus sempervirens) were associated with death in the ancient Middle East and they continue to grow in both Christian and Muslim graveyards. A number of theories have been formed as to why cypress trees and cypress wood have this connection with mourning, but there can be no single explanation. A major story in Ovid reports the transformation of Cyparissus into a cypress tree as coming about after the young man accidentally killed a beloved deer with his javelin. His mourning is eternal.

In all the throng the cone-shaped cypress came; a tree now, it was changed from a dear youth loved by the god who strings the lyre and bow. For there was at one time, a mighty stag held sacred by those nymphs who haunt the fields Carthaean. His great antlers spread so wide, they gave an ample shade to his own head. Those antlers shone with gold: from his smooth throat a necklace, studded with a wealth of gems, hung down to his strong shoulders—beautiful. A silver boss, fastened with little thongs, played on his forehead, worn there from his birth; and pendants from both ears, of gleaming pearls, adorned his hollow temples. Free of fear, and now no longer shy, frequenting homes of men he knew, he offered his soft neck even to strangers for their petting hands. But more than by all others, he was loved by you, O Cyparissus, fairest youth of all the lads of Cea. It was you who led the pet stag to fresh pasturage, and to the waters of the clearest spring. Sometimes you wove bright garlands for his horns, and sometimes, like a horseman on his back, now here now there, you guided his soft mouth with purple reins. It was upon a summer day, at high noon when the Crab, of spreading claws, loving the sea-shore, almost burnt beneath the sun's hot burning rays; and the pet stag was then reclining on the grassy earth and, wearied of all action, found relief under the cool shade of the forest trees; that as he lay there Cyparissus pierced him with a javelin: and although it was quite accidental, when the shocked youth saw his loved stag dying from the cruel wound he could not bear it, and resolved on death. What did not Phoebus say to comfort him? He cautioned him to hold his grief in check, consistent with the cause. But still the lad lamented, and with groans implored the Gods that he might mourn forever. His life force exhausted by long weeping, now his limbs began to take a green tint, and his hair, which overhung his snow-white brow, turned up into a bristling crest; and he became a stiff tree with a slender top and pointed up to the starry heavens. And the God, groaning with sorrow, said; “You shall be mourned sincerely by me, surely as you mourn for others, and forever you shall stand in grief, where others grieve.” Ovid, Metamorphoses 10: 106 - 142 English Translation by Brookes More. Boston. Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922.

The Danaids

The Danaids were the 50 daughters of King Danaus, whose brother, King Aegyptos, had 50 sons. The two fathers had an argument and Aegyptos insisted that his sons marry Danaus’s daughters. Danaus agreed, but instructed the daughters to kill their husbands on their wedding night. Their punishment in Tartarus was to fill a leaking jar or a sieve.

Tantalus

The immortal King Tantalus is another inhabitant of Tartarus, the dungeon of the Underworld. According to Homer (Odyssey 11: 584-590), his punishment for stealing the food of the gods and giving it to mortals is having to stand in water up to his chin. He is perpetually hungry and thirsty, but when he tries to drink the water recedes and when he tries to reach the fruit ripening just above him it moves beyond his reach. This is what it is to be tantalised. In Pindar’s Olympian Odes there is an enormous stone hanging above him and he has to live in eternal fear of it falling on him.

Lethe

Lethe is the goddess of forgetfulness or oblivion, and also one of the rivers of the Underworld.

Aeneas in amaze the wonder views, And fearfully inquires of whence and why; What yonder rivers be; what people press, Line after line, on those dim shores along. Said Sire Anchises: “Yonder thronging souls To reincarnate shape predestined move. Here, at the river Lethe's wave, they quaff Care-quelling floods, and long oblivion." Virgil, Aeneid Book 6: 716 ff English translation by Theodor C. Williams

Basel, Kunstmuseum

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Fahrt zum Hades Der Nachen dröhnt, Cypressen flüstern - Horch, Geister reden schaurig drein; Bald werd' ich am Gestad', dem düstern, Weit von der schönen Erde seyn. Da leuchten Sonne nicht, noch Sterne, Da tönt kein Lied, da ist kein Freund. Empfang die letzte Thräne, o Ferne! Die dieses müde Auge weint. Schon schau ich die blassen Danaiden, Den fluchbeladnen Tantalus; Es murmelt todesschwangern Frieden, Vergessenheit, dein alter Fluß. Vergessen nenn' ich zwiefach Sterben, Was ich mit höchster Kraft gewann, Verlieren - wieder es erwerben - Wann enden diese Qualen? wann? 1 The word 'blassen' (pale) does not appear in the 1824 edition of Mayrhofer's poems. Schubert may have added it, or he may have been working from an earlier draft of the text.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 155.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 155 [167 von 212] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ177450902