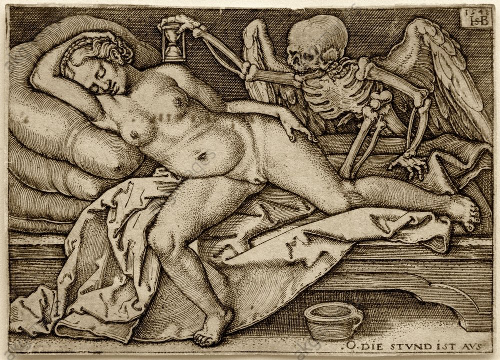

Death and the girl

(Poet's title: Der Tod und das Mädchen)

Set by Schubert:

D 531

[February 1817]

Das Mädchen

Vorüber, ach vorüber,

Geh wilder Knochenmann!

Ich bin noch jung, geh Lieber

Und rühre mich nicht an.

Der Tod

Gib deine Hand, du schön und zart Gebild,

Bin Freund, und komme nicht zu strafen.

Sei gutes Muts! ich bin nicht wild,

Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen!

The girl:

Get away! Oh, get away!

Go away, savage skeleton!

I am still young, go away love!

And don’t bother me.

Death:

Give me your hand, you beautiful, tender image!

I am a friend, and I have not come to punish.

Cheer up! I am not savage,

You are going to sleep gently in my arms!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

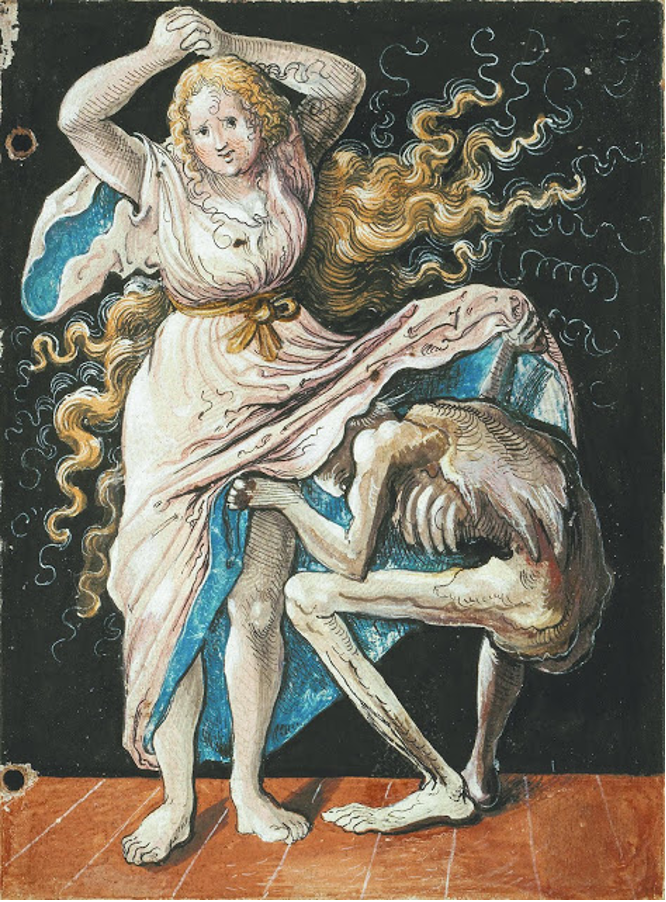

Arms and embracing Bones and skeletons Friends Hands Pictures and paintings Rest Sleep

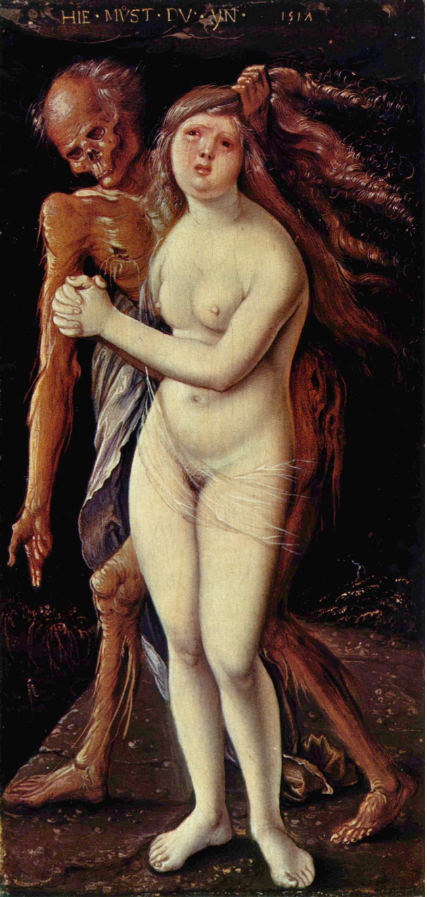

We are not told her name; she is identified simply as a Mädchen, a maiden, an unmarried young woman. The male that arrives is not the husband she was expecting. Death arrives before she is ready for him. She might have expected him in a year or two when giving birth to her first child (he was a particularly frequent visitor at that point), but all she can say now is ‘go away, I am too young.’

None of us are too young, though. There are still plenty of infectious diseases or cancers which can kill young women in the bloom of youth, but most of us now live in a culture where we are encouraged to ‘fight’ such conditions. It seems perverse to embrace death as a friend in the way encouraged by Claudius’s text, yet once the ‘battle’ has been ‘lost’ we are still keen to revert to the language of ‘sleeping gently’ in the arms of death.

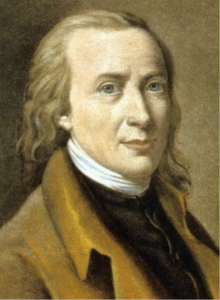

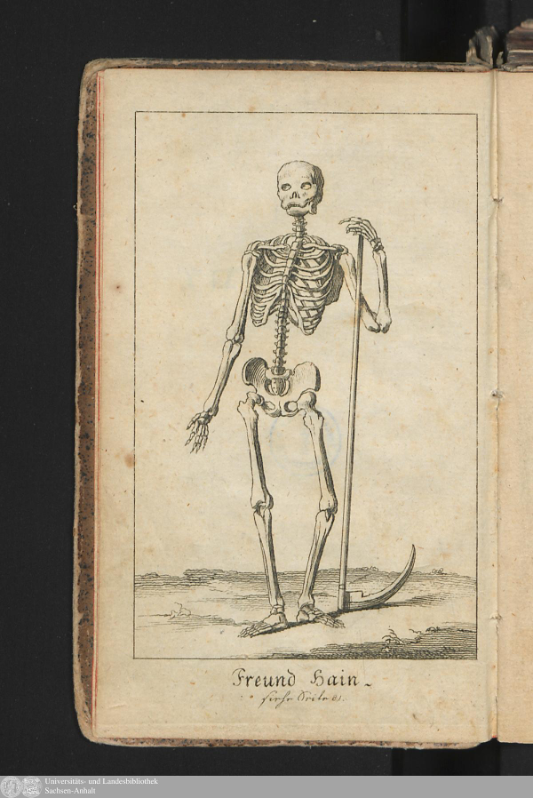

For the poet Matthias Claudius (1740 – 1815), acceptance of death’s inevitability was the basis for accepting the joys of life itself. Indeed his complete poems (ASMUS omnia sua SECVM portans, oder Sämmtliche Werke des Wandsbecker Bothen, Hamburg und Wandsbeck, 1775) had a frontispiece image of a full frontal skeleton holding a scythe, entitled ‘Freund Hain’ (Our Friend Death).

Although this image might seem to echo many of the memento mori shockers that were so common in Europe in the years after the Black Death, the aim seems to be different. This skeleton is not calling on us to repent before it is too late or to give more money to religious institutions. We are being urged to believe him when he says that he has not come to punish us. He is simply a friend who is reaching out his hand to us.

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Der Tod und das Mädchen Das Mädchen Vorüber! Ach, vorüber! Geh wilder Knochenmann! Ich bin noch jung, geh Lieber1! Und rühre mich nicht an. Der Tod Gib deine Hand, Du schön und zart Gebild! Bin Freund, und komme nicht, zu strafen. Sey gutes Muths! ich bin nicht wild, Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen! 1 Graham Johnson points out that there is an ambiguity here. The girl could be addressing death as her 'dear one', her beloved, or 'Lieber' could be a contraction of 'du Lieber Gott', in which case she is saying 'Go away, for God's sake!'

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s probable source, ASMUS omnia sua SECUM portans, oder Sämmtliche Werke des Wandsbecker Bothen, I. und II. Theil. Beym Verfasser, und in Commißion bey Fr. Perthes in Hamburg. [1774], page 199; and with Poetische Blumenlese Auf das Jahr 1775. Göttingen und Gotha bey Johann Christian Dieterich, page 157.

To see an early edition of this text, go to page 199 here: https://resolver.sub.uni-hamburg.de/kitodo/PPN840695020