Welcome and departure

(Poet's title: Willkommen und Abschied)

Set by Schubert:

D 767

[early December 1822]

Part of Goethe: the December 1822 settings

Es schlug mein Herz; geschwind zu Pferde,

Es war getan fast eh’ gedacht;

Der Abend wiegte schon die Erde,

Und an den Bergen hing die Nacht:

Schon stand im Nebelkleid die Eiche,

Ein aufgetürmter Riese, da,

Wo Finsternis aus dem Gesträuche

Mit hundert schwarzen Augen sah.

Der Mond von einem Wolkenhügel

Sah kläglich aus dem Duft hervor,

Die Winde schwangen leise Flügel,

Umsausten schauerlich mein Ohr;

Die Nacht schuf tausend Ungeheuer;

Doch frisch und fröhlich war mein Mut:

In meinen Adern welches Feuer,

In meinem Herzen welche Glut!

Dich seh ich, und die milde Freude

Floss von dem süßen Blick auf mich,

Ganz war mein Herz auf deiner Seite

Und jeder Atemzug für dich.

Ein rosenfarbnes Frühlingswetter

Umgab das liebliche Gesicht,

Und Zärtlichkeit für mich – ihr Götter!

Ich hofft’ es, ich verdient’ es nicht.

Doch ach, schon mit der Morgensonne

Verengt der Abschied mir das Herz,

In deinen Küssen, welche Wonne,

In deinem Auge welcher Schmerz!

Ich ging, du standst und sahst zur Erden

Und sahst mir nach mit nassem Blick,

Und doch, welch Glück geliebt zu werden,

Und lieben, Götter, welch ein Glück.

My heart was pounding; quick, onto the horse!

It was done almost before the thought struck;

The evening was lulling the earth

And night was hanging on the hills:

Already standing dressed in mist was an oak tree,

A towering giant there,

Where darkness was looking out of the bushes

With a hundred black eyes.

From behind a hill of clouds the moon

Looked miserably out through the haze,

The winds rose up on gentle wings,

Rustling spine-chillingly around my ears;

The night created a thousand monsters;

Yet my mood was fresh and cheerful:

What fire in my veins!

What a glow in my heart!

I see you, and gentle joy

Flowed from your sweet glance onto me;

My heart was completely by your side

And each intake of breath was for you.

The pink spring weather

Glowed around your lovely face,

Along with tenderness for me – ye gods!

It is what I had hoped for, I did not deserve it!

But alas as soon as the sun rose in the morning

Departure started pressing on my heart:

In your kisses, what bliss!

In your eyes, what pain!

I left, you were standing there looking down at the ground,

And you cried as you watched me go:

And yet, what happiness to be loved!

And being in love, gods, what happiness!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Black Blood Breath and breathing Clouds Evening and the setting sun Eyes Farewell and leave taking Fire Gazes, glimpses and glances Greetings Hearts Hills and mountains Hope Horses Journeys Kissing Joy Mist and fog Morning and morning songs Pain Night and the moon Oak trees Riding – on horseback Rocking Roses and pink Spring (season) Tears and crying Wind

Goethe was one of those poets who used his own personal experience as the basis of his work, but in doing so he was so inventive and convincing that the written texts that emerged transcended what ‘actually’ happened. Readers have a sense that they are directly participating in the writer’s own sensations, yet they are often shocked to discover that the poem that has stirred them is not a ‘reliable’ record of events. In the case of the poet’s relationship with Friederike Brion in 1771, the myth-making began at the time, and all of Goethe’s later references to and reworkings of the episode (particularly in Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, Faust and his autobiography, Dichtung und Wahrheit) add further levels of confusion and distraction. The story continued to be embroidered up until Franz Léhar wrote an operetta, Friederike, on the subject in 1928 (with Richard Tauber singing the part of Goethe – a tenor, of course).

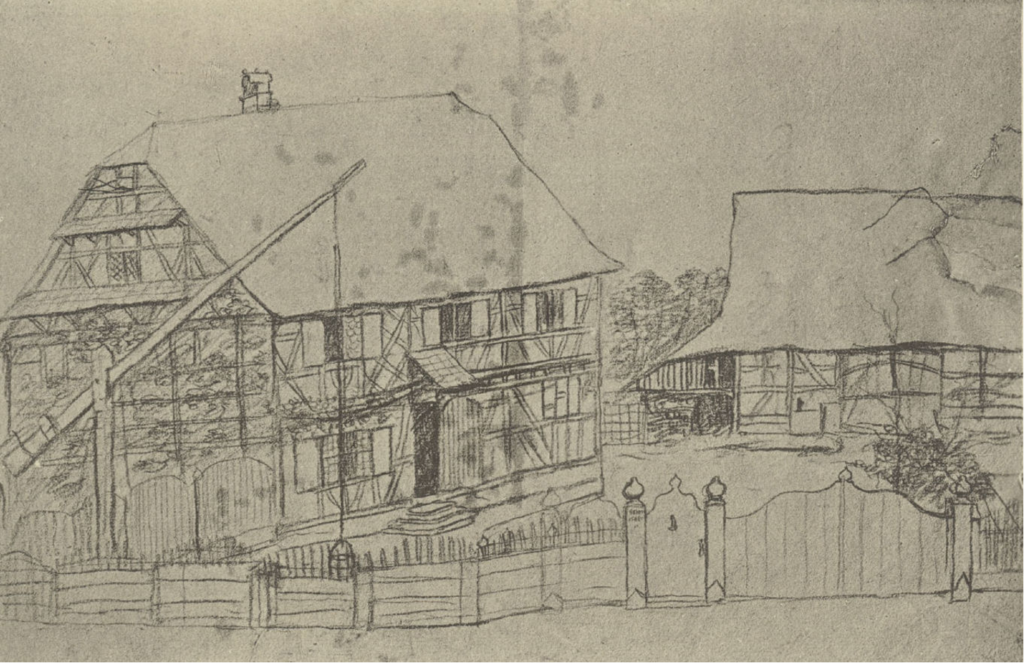

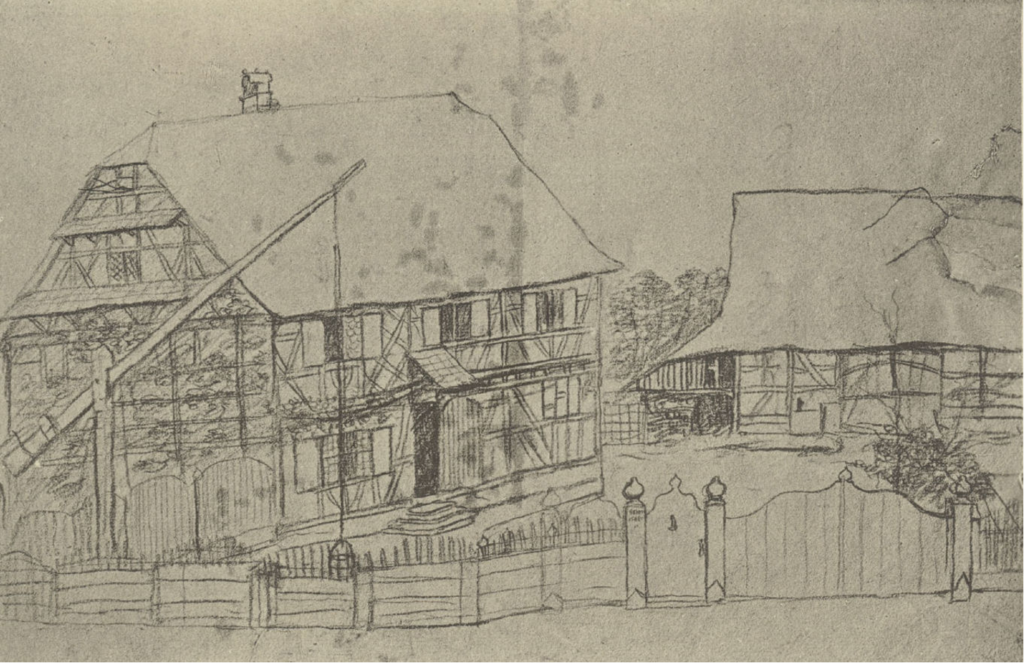

Friederike Brion (1752 – 1813) was the third of five surviving children of Johann Jakob Brion, the Lutheran Pastor in the Alsatian village of Sessenheim (which Goethe usually wrote as Sesenheim). At the time of their relationship (late 1770 and much of 1771) Goethe was a 21 year-old law student at the University of Strasbourg (about 40km southwest of Sessenheim), but he was clearly spending much more time writing and translating poetry than studying law (he claimed that he already knew everything that was being presented in the lectures). His visits to Sessenheim became longer and longer and by the middle of the summer he had spent so much time with Friederike that he could not stop people assuming that they were engaged. This was the trigger that led him to break off the relationship and leave the area. Friederike never married.

Whatever guilt or embarrassment the author felt did not prevent him from publishing what he called his ‘Sesenheim Songs’: ‘Mit einem gemalten Band’, ‘Mailied’ (both set famously by Beethoven), ‘Willkommen und Abschied’, and ‘Heidenröslein’ (Schubert’s D 257). Nor did it prevent him fantasising about declaiming his own translations of Ossian (a task Goethe undertook at Sessenheim under the influence of Herder) in a famous scene in Die Leiden des jungen Werthers in which the young poet returns to Charlotte after she has rejected him.

Although ‘Willkommen und Abschied’ was first drafted in the midst of the ‘Sesenheim Idyll’, when the poet was most definitely still ‘welcome’, it was not made known to the world until after the couple had said their farewells. The Abschied of the title is therefore not just about the departure after a blissful night together but it relates to the end of a life-changing relationship. In writing the poem Goethe is already transforming and processing the experience: the whole thing was something he had hoped for but he admits was something he did not deserve.

Goethe has presented the story in such a way that readers are almost invited to come to the wrong conclusion about the relationship. It is inconceivable that a respectable pastor’s daughter would not have been properly chaperoned during her lover’s visit, particularly if he was staying overnight in the parsonage. Yet this is a poem about fully requited love and ecstatic passion, with night-time kisses and a full range of ‘tenderness’. When the experience was reworked a few years later in Faust, Friederike has turned into Gretchen, who finds herself pregnant by the golden tongued young student. If the real-life Johann Wolfgang Goethe was genuinely worried about sullying Friederike’s reputation he had a strange way of showing it.

So, we have to conclude that the poem is not about (and was never really ‘about’) what actually happened. What it DOES capture is the excitement and the bliss of infatuation and the inner fantasy of a young man discovering the thrill of being loved and in love. The anxious ride on horseback, with the looming giant of an oak tree and the sense of being watched by a hundred critical and disapproving eyes, evokes the uncertainties of a young lad worried that he has gone too far and that he is presuming too much by turning up unannounced at his beloved’s home. The wind terrifies him and the encroaching night creates monsters, but his inner passion drives him on.

One glance from the beloved transforms everything. What had there ever been to worry about? The monsters of the night and the black eyes of disapproval have given way to the welcoming face and eyes of a lover lit up in the pink glow of springtime. By now it is fairly clear that we are in the realm of feeling rather than physical description, so we have to ignore the fact that night fell long ago! Similarly, when morning comes and welcome gives way to farewell and departure, we should not be so literal as to ask how the poet setting off so determinedly on his horse could know that the girl behind him was looking down at the earth and starting to cry. What we need to concentrate on is the inner realisation that he has achieved: that the loss and longing which follows the bliss of requited love is something different from the more common form of yearning for an unattainable object. Departure after such a welcome is a new beginning.

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Willkommen und Abschied Es schlug mein Herz; geschwind zu Pferde! Es war gethan fast eh' gedacht; Der Abend wiegte schon die Erde Und an den Bergen hing die Nacht: Schon stand im Nebelkleid die Eiche Ein aufgethürmter Riese da, Wo Finsterniß aus dem Gesträuche Mit hundert schwarzen Augen sah. Der Mond von einem Wolkenhügel Sah kläglich aus dem Duft hervor, Die Winde schwangen leise Flügel, Umsaus'ten schauerlich mein Ohr; Die Nacht schuf tausend Ungeheuer; Doch frisch und fröhlich war mein Muth: In meinen Adern welches Feuer! In meinem Herzen welche Gluth! Dich seh ich1, und die milde Freude Floß von dem süßen Blick auf mich; Ganz war mein Herz auf deiner Seite Und jeder Athemzug für dich. Ein rosenfarbnes Frühlingswetter Umgab das liebliche Gesicht, Und Zärtlichkeit für mich - Ihr Götter! Ich hofft' es, ich verdient' es nicht! Doch ach schon mit der Morgensonne Verengt der Abschied mir das Herz: In deinen Küssen, welche Wonne! In deinem Auge, welcher Schmerz! Ich ging, du standst und sahst zur Erden, Und sahst mir nach mit nassem Blick: Und doch, welch Glück geliebt zu werden! Und lieben, Götter, welch ein Glück! 1 Schubert appears to have followed the misprint in the 1810 Viennese edition of Goethe's poems here. All other editions have the past tense at this point, not the present: 'Dich sah ich' (I saw you) not 'Dich seh ich' (I see you).

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s probable source, Goethe’s sämmtliche Schriften. Siebenter Band. / Gedichte von Goethe. Erster Theil. Lyrische Gedichte. Wien, 1810. Verlegt bey Anton Strauß. In Commission bey Geistinger pages 39-40; with Goethe’s Werke, Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand, Erster Band, Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cottaschen Buchhandlung, 1827, pages 75-76; and with Goethe’s Schriften, Achter Band, Leipzig, bey Georg Joachim Göschen, 1789, pages 115-116 (here with the title Willkomm und Abschied.

Note: First published 1775 in an earlier version as part of the poem Neue Liebe, Neues Leben (stanzas 4-7) in Iris. Zweyter Band. Drittes Stück.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 39 [53 von 418] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ163965701