Traveller's night song

(Poet's title: Wanderers Nachtlied)

Set by Schubert:

D 768

[before 25th May 1824]

Über allen Gipfeln

Ist Ruh,

In allen Wipfeln

Spürest du

Kaum einen Hauch;

Die Vöglein schweigen im Walde,

Warte nur, balde

Ruhest du auch.

Over all the hill tops

There is rest,

In all the tree tops

You can feel

Barely a breath;

The little birds have fallen silent in the woods.

Just wait, soon

You too will be at rest.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Birds Breath and breathing Evening and the setting sun Hills and mountains Night and the moon Noise and silence Not moving Rest Serenades and songs at evening Trees (general) Waiting Walking and wandering Wind Woods – large woods and forests (Wald)

"On 6 September 1780 at the start of [a] tour in the Thuringian Forest, on a calm evening with a majestic sunset and thin columns of smoke rising from the charcoal-burners' fires, Goethe, in total solitude, wrote to Frau von Stein from a wooden refuge on the highest of the peaks round Ilmenau, 'if only my thoughts of today were written down complete: there are some good things among them'. This time he was right: one of his thoughts of the day was written down, by Goethe himself, a little before 8 o'clock on the wall of the hut, and what he wrote has become in the German-speaking world - for it is untranslatable - the best-known of all poems, by anyone: Über allen Gipfeln Ist Ruh', In allen Wipfeln Spürest du Kaum einen Hauch; Die Vögelein schweigen im Walde. Warte nur, balde Ruhest du auch. There is little sensible that literary criticism can say about something so delicate and so matchless. But for the biographer one feature of the poem is very revealing: its use of the word 'you'. The word refers either to Goethe or to the reader or to both - that is the nature of the dialogue in Goethe's soul - but the 'you' is not - not specifically, or by allusion - the woman to whom Goethe was writing only minutes before, and after, he composed the poem. Though for years he could not bring himself to acknowledge it, the sources of his poetry ran deeper, and purer, than 'the sweet conversation of my inmost heart' that was his mental discourse with Charlotte von Stein." Nicolas Boyle, Goethe. The Poet and the Age. Volume 1: The Poetry of Desire (1749 - 1790) Oxford University Press 1991 page 266

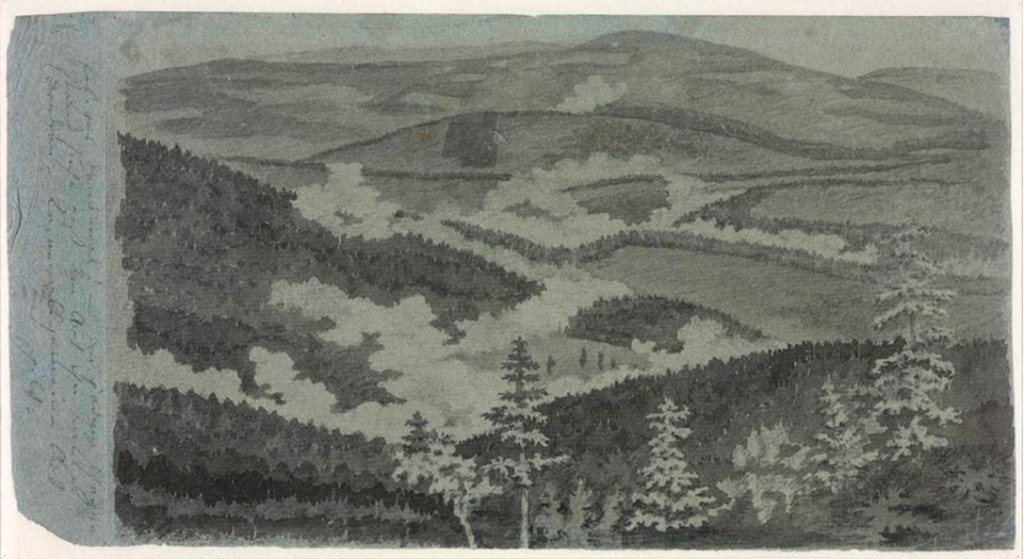

This was not Goethe’s first visit to the hut overlooking Ilmenau, nor was it to be his last. He found himself there on many occasions as part of his surveying and geological work for the Duke of Weimar (who had inherited the impoverished region of Ilmenau and its abandoned silver mines). In July 1776 he made a sketch of the view, emphasising the mist (or is it the charcoal-burners’s smoke?) as well as the peaks (Gipfeln) and tree-tops (Wipfeln) that appear in the poem. When he returned in August 1813 he found that the poem he had written (in pencil) on the wall had faded, so he re-traced it. His final visit was on 27th August 1831 (the day before his 82nd birthday). According to his companion on that occasion, the geologist Johann Christian Mahr, Goethe re-read the poem in the hut “and tears flowed down his cheeks. Very slowly he drew a snow-white handkerchief from his dark brown coat, dried his eyes and spoke in a soft, mournful tone: ‘Yes, wait! Soon you too will be at rest!'”[1]

One of Goethe’s greatest achievements in this simple poem is to avoid the doggerel that could have resulted from the (rather too obvious) rhyme of Gipfeln (peaks) and Wipfeln (tree tops). Yet since he was looking out at the landscape with the eyes of someone involved in a detailed analysis of the land and its vegetation he was able to see the inner connections that bound the concepts (not just the words). His geological studies had led him towards a critical understanding of the shape of the hills (Gipfeln) and in 1780 he was beginning his research on botany, which was eventually to lead to the publication of his theory of plant morphology, Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären (1790). What he saw on that calm September evening in 1780 was the inner unity of vegetable and mineral, and the possibility that scientific understanding might achieve a synthesis of geology, botany, meteorology and biology (‘kaum einen Hauch’ seems to refer to feeling barely a breath of wind, or of any animal, including ourselves). Like so many other scientific geniuses (such as Darwin and Einstein) Goethe was able to see the connections between ideas based on a poetic sensitivity.

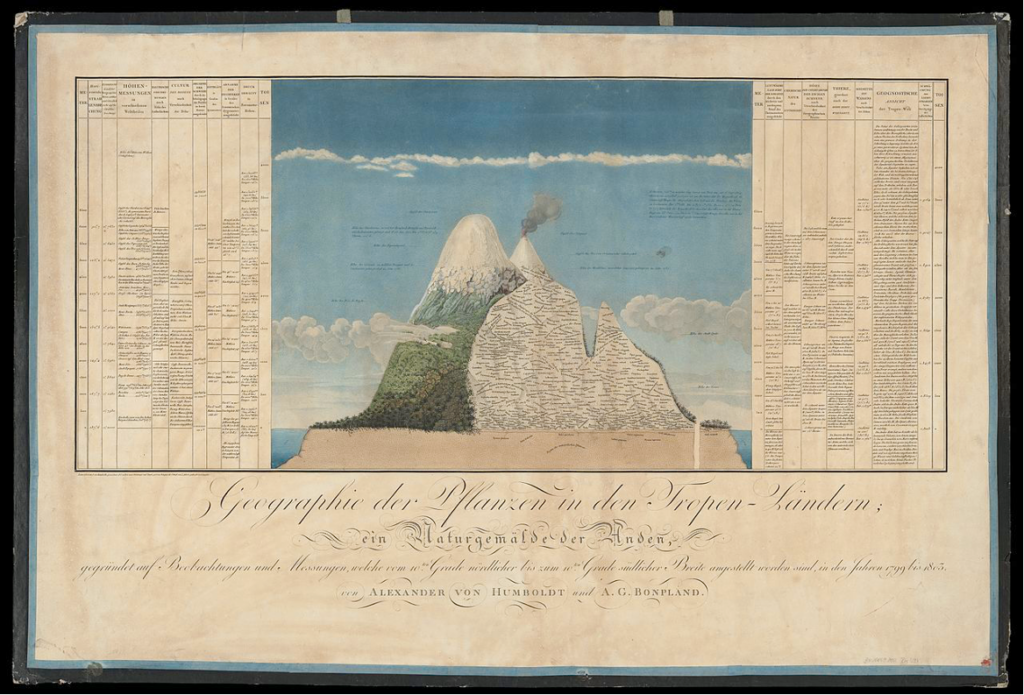

His insight was carried forward in the next generation in the pioneering work of Alexander von Humbolt, the founder of ‘ecology’ (the study of inter-connections and inter-dependence in nature). Goethe first met Humbolt at Jena (not far from Ilmenau) in 1794, a few years before the latter set off on his famous journey to South America, where he formulated his geographical theory of plants (in particular the relationship between latitude and altitude). As he climbed what was then believed to be the highest peak on earth (Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador) and looked out over the changing vegetation the higher he went, Humboldt must have remembered his conversations with Goethe and the words of his most famous lyric.

Yet it is not necessary to be a ground-breaking scientist or explorer to appreciate the power of Goethe’s short text. All that really matters is that we know what it is to be tired, what it is to long for rest and peace (the word ‘Ruhe’ entails both of these ideas). Perhaps, though, we also need the ability to stop and hear the silence that comes as the wind falls and the birds roost at sunset. For too many of us the twittering never ends and we fail to take the opportunity to be quiet. ‘Schweigen’ (to be silent / not to say something) is an active verb in German. The birds act decisively when they fall silent in the evening. Can we say the same of ourselves? Will we too soon rest?

[1] Graham Johnson, Franz Schubert. The Complete Songs Yale University Press 2014 Volume Three page 555. The hut burned down in 1870 but a replica was built in 1874.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ilmenau_Goethehaeuschen.jpg

☙

Original Spelling Wandrers Nachtlied Über allen Gipfeln Ist Ruh', In allen Wipfeln Spürest du Kaum einen Hauch; Die Vögelein schweigen im Walde. Warte nur, balde Ruhest du auch.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s probable source, Goethe’s Werke. Erster Band. Original-Ausgabe. Wien, 1816. Bey Chr. Kaulfuß und C. Armbruster. Stuttgart. In der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. Gedruckt bey Anton Strauß page 111; with Goethe’s Werke. Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand. Erster Band. Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. 1827, page 109; and with Goethe’s Werke. Erster Band. Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. 1815, page 99.

Note: in many older editions, the spelling of the capitalized word “über” becomes “Ueber”, but this is often due to the printing process and not to rules of orthography.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 111 [123 von 474] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ223421802