Orientation

DECIUS

Here lies the east. Doth not the day break here?

CASKA

No.

CINNA

O pardon, sir, it doth, and yon grey lines

That fret the clouds are messengers of day.

CASKA

You shall confess that you are both deceived.

Here, as I point my sword, the sun arises,

Which is a great way growing on the south,

Weighing the youthful season of the year.

Some two months hence, up higher toward the north

He first presents his fire, and the high east

Stands as the Capitol, directly here.

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar Act II Scene 1

Before dawn on the Ides of March Caesar’s assassins get involved in this very odd dispute about locating the east. Shakespeare seems to be dramatising what it is to be disorientated.

Of course the sun is going to rise in the east, but that is a general direction, not a fixed location.

Cultures around the world have long oriented temples and sacred spaces towards the East, presumably based on the idea that sunrise is a promise of renewal and new life. In most places, though, a fixed pointer to the rising sun might only be accurate once a year! Getting our bearings is never as easy as we initially assume.

Kosegarten’s Von Ida begins with the standard image of the bright sunrise in the East only for us then to realise that down here on earth, the weather is gloomy and the speaker is bereft:

Der Morgen blüht;

Der Osten glüht;

Es lächelt aus dem dünnen Flor

Die Sonne matt und krank hervor,

Denn, ach, mein Liebling flieht!

Morning is blossoming,

The East is glowing;

Smiling out of the fine veil of mist

Is the sun, languid and sickly.

Because, oh no, my darling has fled!

Kosegarten, Von Ida D 228

Schiller used the image of a pilgrimage to the East as a symbol of human striving for renewal, but understood that the goal might be unachievable. The river that promises to take us towards that new day might be offering false hope.

Berge lagen mir im Wege,

Ströme hemmten meinen Fuß,

Über Schlünde baut' ich Stege,

Brücken durch den wilden Fluss.

Und zu eines Stroms Gestaden

Kam ich, der nach Morgen floss,

Froh vertrauend seinem Faden

Warf ich mich in seinen Schoß.

Hin zu einem großen Meere

Trieb mich seiner Wellen Spiel,

Vor mir liegt's in weiter Leere,

Näher bin ich nicht dem Ziel.

Ach kein Weg will dahin führen,

Ach der Himmel über mir

Will die Erde nicht berühren,

Und das Dort ist niemals Hier.

Mountains lay in my way,

Streams hemmed in my feet,

I built footbridges across crevices,

I built bridges over the savage river.

And I came to the bank of a stream

That was flowing to the East, I came there

And happily trusting its current

I threw myself into its lap.

I was taken off to a great ocean,

The play of its waves carried me along,

Lying in front of me is a broad expanse,

I am no nearer to my goal.

Oh, no path is going to lead there,

Oh the sky above me

Is not going to touch the earth,

And 'there' is never 'here'.

Schiller, Der Pilgrim D 794

The character in Seidl’s Der Wanderer an den Mond is more of a tramp than a pilgrim, but he experiences similar confusion as he contrasts his own seemingly pointless travelling with the regular path taken by the moon. The human speaker can never settle but the moon seems to be at home everywhere, from its cradle in the West to its grave in the East.

Just a moment! That can’t be right. Has there been a misprint? Like the sun, the moon rises (has its cradle) in the East and sets (into its grave) in the West. There has been a great deal of debate about this in the literature, but it may well be that the poet is simply trying to convey the confusion of another dis-orientated individual.

Ich auf der Erd, am Himmel du,

Wir wandern beide rüstig zu: -

Ich ernst und trüb, du mild und rein,

Was mag der Unterschied wohl sein?

Ich wandre fremd von Land zu Land,

So heimatlos, so unbekannt,

Bergauf, bergab, waldein, waldaus,

Doch bin ich nirgend, ach, zu Haus.

Du aber wanderst auf und ab

Aus Westens Wieg in Ostens Grab,

Wallst länderein und länderaus,

Und bist doch, wo du bist, zu Haus.

Der Himmel, endlos ausgespannt,

Ist dein geliebtes Heimatland.

O glücklich, wer, wohin er geht,

Doch auf der Heimat Boden steht.

I am on the earth, you are in the sky,

We are both resolutely walking along:

I am serious and gloomy, you are gentle and pure,

What can explain the difference?

I walk on as a stranger from land to land,

So homeless, so unknown to others;

Up mountains and down mountains, into forests and out of forests,

Yet I am never - alas! - at home.

You, however, walk up and down

From the cradle in the west to the grave in the east,

On your pilgrimage you progress into lands and out of lands

And yet, wherever you are, you are at home.

The sky, endlessly stretched out,

Is your beloved homeland:

Oh happy is he who, wherever he goes,

Is still standing on his home ground!

Seidl, Der Wanderer an den Mond D 870

Blowing in the wind

Across most of the German-speaking lands the prevailing winds are westerlies, carrying moist air. At times, though, easterlies bring in drier weather across the steppes from central Asia. How are these meteorological systems reflected in German poetry?

Westerly winds, unsurprisingly, are connected with storms and destruction:

Auf ewig dein, wenn Berg und Meere trennen,

Wenn Stürme dräun,

Wenn Weste saüseln oder Wüsten brennen:

Auf ewig dein.

For ever yours! When mountains and oceans split up,

When storms threaten.

When westerly winds blow or deserts burn:

For ever yours!

Matthisson, Widerhall D 428

Sieh, die Linde blühet noch,

Als du heute von ihr gehst;

Wirst sie wieder finden, doch

Ihre Blüten stiehlt der West.

Look, this lime tree is still in blossom

As you depart from it today;

When you come across it again, though,

The westerly wind will have stolen its blossoms.

von Széchényi, Die abgeblühte Linde D 514

However, gentler westerlies can carry refreshing showers and offer inner renewal:

Linde Weste wehen,

Atmen Balsamdüfte

Von Jasmingesträuchen,

Und von Veilchenaun.

The gentle west winds are stirring,

Breathing in the scent of balsam

From the jasmine bushes

And from the violet meadows.

Stolberg, Linde Weste wehen D 725

Der Frühlingssonne holdes Lächeln

Ist meiner Hoffnung Morgenrot,

Mir flüstert in des Westes Fächeln

Der Freude leises Aufgebot.

Ich komm, und über Tal und Hügel,

O süße Wonnegeberin,

Schwebt, auf des Liedes raschem Flügel,

Der Gruß der Liebe zu dir hin.

The beauteous smile of the spring sun

Is the dawn of my hope;

In the stirring of the west wind I can hear the whispering

Of joy's gentle announcement.

I am coming, and over valley and hill,

Oh sweet bestower of bliss,

On the rapid wings of song may it float

Towards you - this greeting of love.

Schlegel, Wiedersehn D 855

Similar evocations of spring carried on westerly winds appear in Uz’s Gott im Frühlinge (D 448) and Kind’s Hänflings Liebeswerbung (D 552).

There are fewer references to easterly winds. Kosegarten’s Ida complains that the rough east wind has destroyed her roses, but in Rückert’s Daß sie hier gewesen (D 775) gentle breezes carry the scent of the beloved from the Orient.

Denn unsre Blumen sind verdorrt,

Entlaubt sind unsre Linden.

Ihr Rosen, die der rauhe Ost

In ihrem Knospen pflückte;

Ihr Nelken, die der frühe Frost

Halbaufgeschlossen knickte;

Ist euer Los nicht auch mein Los?

Seid ihr nicht, was ich werde?

Entkeimt´ ich nicht, wie ihr, dem Schoß

Der mütterlichen Erde?

For our flowers have withered,

Our lime trees have shed their foliage.

You roses, which the rough easterly wind

Plucked while you were still buds;

You carnations, which an early frost

Snapped off while still half closed;

Is your fate not also my fate?

Are you not what I am going to be?

Did I not spring, like you, from the womb

Of mother Earth?

Kosegarten, Idens Schwanenlied D 317

Dass der Ostwind Düfte

Hauchet in die Lüfte,

Dadurch tut er kund,

Dass du hier gewesen.

The fact that the east wind takes scents and

Breathes them into the breezes

Is something that proclaims

The fact that you have been here.

Rückert, Daß sie hier gewesen D 775

West-East Divan

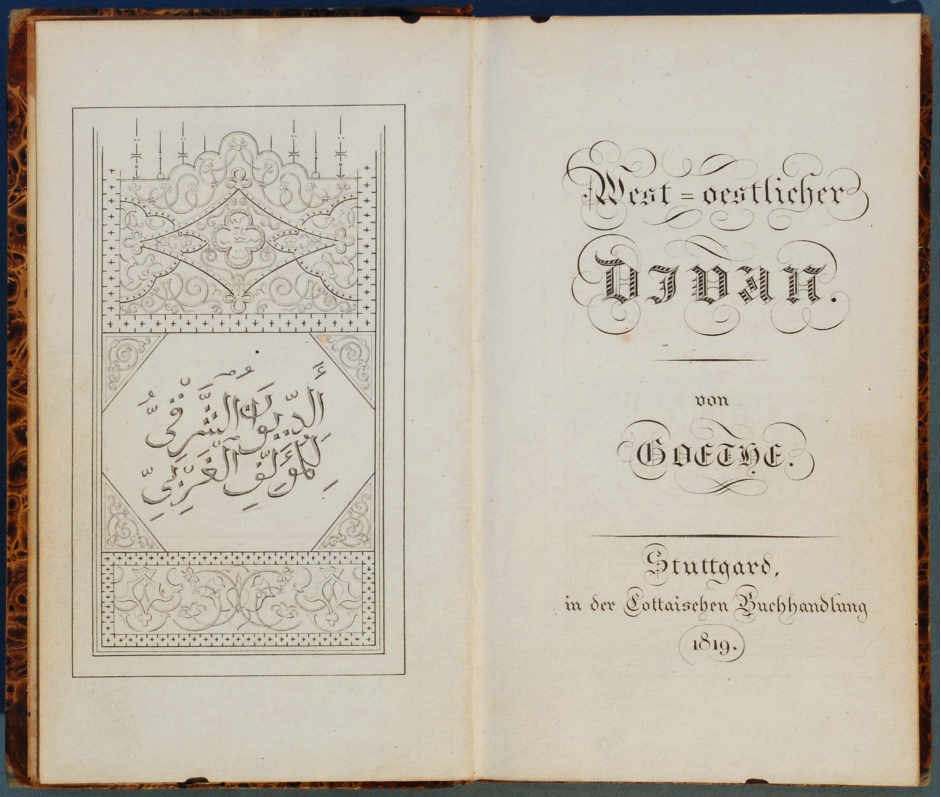

Marianne von Willemer’s two Suleika poems (published under Goethe’s name in his West-östlicher Divan in 1819) give voice to the East and the West wind in turn. Marianne in Frankfurt takes inspiration from Goethe to her east (Weimar) just as Suleika feels the breath (Athem) of her beloved Hatem coming from the East (Shiraz in Persia). She sends her reply on the West wind.

Was bedeutet die Bewegung?

Bringt der Ost mir frohe Kunde?

Seiner Schwingen frische Regung

Kühlt des Herzens tiefe Wunde.

Kosend spielt er mit dem Staube,

Jagt ihn auf in leichten Wölkchen,

Treibt zur sichern Rebenlaube

Der Insecten frohes Völkchen.

Lindert sanft der Sonne Glühen,

Kühlt auch mir die heißen Wangen,

Küsst die Reben noch im Fliehen,

Die auf Feld und Hügel prangen.

Und mir bringt sein leises Flüstern

Von dem Freunde tausend Grüße;

Eh noch diese Hügel düstern,

Grüßen mich wohl tausend Küsse.

Und so kannst du weiter ziehen,

Diene Freunden und Betrübten.

Dort wo hohe Mauern glühen,

Find ich bald den Vielgeliebten.

Ach! die wahre Herzenskunde,

Liebeshauch, erfrischtes Leben,

Wird mir nur aus seinem Munde,

Kann mir nur sein Atem geben.

What does this movement mean?

Is the Easterly wind bringing me a joyful message?

The fresh stirring of its wings

Cools the deep wounds in my heart.

As it caresses it is playing with the dust,

It chases it up to make small, light clouds,

It drives insects towards the secure foliage of the vine -

A joyful little population of insects.

It gently soothes the glow of the sun,

It also cools my hot cheeks for me,

And as it passes by it even kisses the vines,

Which are resplendent on the fields and hills.

And its gentle whisper brings me

A thousand greetings from my friend;

Even before these hills grow dark

As many as a thousand kisses are going to greet me.

And so you can travel on further!

Offer your services to friends and those who are distressed.

There where high walls are glowing,

That is where I shall soon find the one I love so much.

Oh, the true message from the heart,

The breath of love, refreshed life

Will only come to me from his mouth,

Only his breath can give it to me.

Willemer, Suleika I D 720

Ach, um deine feuchten Schwingen,

West, wie sehr ich dich beneide,

Denn du kannst ihm Kunde bringen,

Was ich in der Trennung leide.

Die Bewegung deiner Flügel

Weckt im Busen stilles Sehnen,

Blumen, Auen, Wald und Hügel

Stehn bei deinem Hauch in Tränen.

Doch dein mildes sanftes Wehen

Kühlt die wunden Augenlider,

Ach für Leid müsst ich vergehen,

Hofft ich nicht zu sehn ihn wieder.

Eile denn zu meinem Lieben,

Spreche sanft zu seinem Herzen,

Doch vermeid ihn zu betrüben

Und verbirg ihm meine Schmerzen.

Sag ihm, aber sag's bescheiden,

Seine Liebe sei mein Leben,

Freudiges Gefühl von beiden

Wird mir seine Nähe geben.

Oh, those wings of yours that are heavy with moisture

Are what I very much envy you, West wind:

Since you can carry him news about

What I am suffering because of this separation!

The movement of your wings

Awakens a quiet longing in my breast;

Flowers, meadows, woods and hills

Burst into tears when you breathe.

However, your gentle, smooth stirring

Cools wounded eyelids;

Oh, I would have to die of pain

If I could not hope to see him again.

Hurry then to my beloved,

Speak softly to his heart;

Yet be careful not to distress him

And hide my torments from him.

Tell him, but tell him diplomatically,

That his love is my life,

That a joyful awareness of both

Is what his proximity will give me.

Willemer, Suleika II D 717

This overcoming of distance was central to Goethe’s project in the West-östlicher Divan. Time and space are conquered as a modern German poet takes on the voice of Hafiz, a Persian writer who had been dead for over 400 years.

Wer sich selbst und andre kennt

Wird auch hier erkennen:

Orient und Occident

Sind nicht mehr zu trennen.

Anyone who knows themselves and others

Will also now admit this:

The East and the West

Are no longer to be separated.

Goethe, draft for West-östlicher Divan

Either / Or; Both /And

For many of us who grew up in during the Cold War ‘the East’ and ‘the West’ were definitely separated. There was a metaphorical iron curtain and a concrete wall. East and West were not directions or winds but regions and ideologies.

A couple of generations earlier, the connotations of ‘East’ and ‘West’ were slightly different, but they were similarly based on the Either / Or assumption. As Western European powers developed their Empires in ‘the East’, it was definitely a matter of ‘us’ and ‘them’. We might see this attitude expressed in all of its raw racism in a famous couplet by Rudyard Kipling from 1889:

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God's great Judgment Seat;

However, if we read the whole of ‘The Ballad of East and West’ from which these lines are taken, we see that it is a surprising story of shared values between the British soldiers in the North West Frontier of India and their Pashto adversaries. The couplet is part of a quatrain which appears both at the beginning and end of the ballad to challenge the reader’s assumptions. Instead of thinking of East and West as a matter of Either / Or, we are urged to acknowledge what we have in common.

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God's great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the earth.

Kipling wrote The Ballad of East and West at the high point of the British Empire, when Orientalist assumptions about the ‘Otherness’ of the East were most pervasive, but a couple of generations before that (in Goethe’s time, in fact) there was a much greater openness and permeability. William Dalrymple has demonstrated (in White Mughals, 2002) the passion of many East India Company employees around 1800 to adopt the best of what Indian culture had to offer.

Unlike those of us who grew up either in the West or in the East, Schubert lived his whole life in Vienna, always in the middle, at the intersection of both east and west. In his final years he showed a genuine passion for Persian poetic forms, as in his settings of Rückert’s ghazals (Oestlichen Rosen) and Goethe’s channelling of Hafiz (West-östlicher Divan), while on his deathbed he was looking west as he took solace in the novels of Fennimore Cooper.

Be so kind as to assist me in this desperate situation by means of literature. Of Cooper's I have read 'The Last of the Mohicans,' 'The Spy,' 'The Pilot' and 'The Pioneers.' If by any chance you have anything else of his, I implore you to deposit it with Frau von Bogner at the coffee-house for me.

12th November 1828

O. E. Deutsch ed., Schubert. A Documentary Biography. Translation by Eric Blom London 1946 p. 820

☙

Descendant of:

SPACE (location)Texts with this theme:

- Die Sterne (Was funkelt ihr so mild mich an), D 176 (Johann Georg Fellinger)

- Sehnsucht der Liebe, D 180 (Theodor Körner)

- Jägerlied, D 204 (Theodor Körner)

- Jägers Abendlied, D 215, D 368 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Von Ida, D 228 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Das Abendrot, D 236 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Shilric und Vinvela, D 293 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Idens Schwanenlied, D 317 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Widerhall, D 428 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Gott im Frühlinge, D 448 (Johann Peter Uz)

- Liedesend, D 473 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die abgeblühte Linde, D 514 (Ludwig (Lajos) Graf Széchényi von Sárvári-Felsö-Vidék)

- Hänflings Liebeswerbung, D552 (Johann Friedrich Kind)

- Das Abendrot (Du heilig, glühend Abendrot!), D 627 (Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber)

- Suleika II, D 717 (Marianne von Willemer)

- Suleika I, D 720 (Marianne von Willemer)

- Linde Weste wehen, D 725 (Christian Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Auf dem Wasser zu singen, D 774 (Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Dass sie hier gewesen, D 775 (Friedrich Rückert)

- Der Pilgrim, D 794 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Wiedersehn, D 855 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Der Wanderer an den Mond, D 870 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Sehnsucht (Die Scheibe friert), D 879 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)