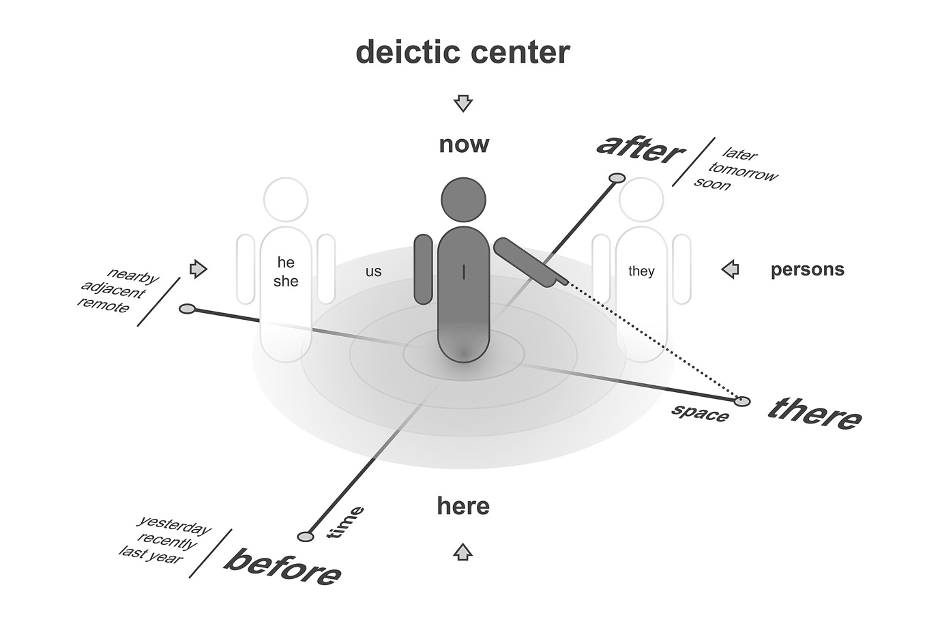

Come and go, here and there, bring and take, this and that. These pairs are basic to the structure of many languages, including English and German. Linguists use the term ‘deixis’ to help them analyse how these terms structure our perception of the world around us.

As always, these simplest of words turn out to be the hardest to understand. “Here she comes,” seems straightforward enough, and perhaps “There she blows” makes sense if the speaker and listener can both see a whale. But why do people say “Here we go” when starting out on a challenge? Where or what does ‘here’ refer to? There’s the question.

It is never just a question of where the speaker is in relation to the listener. It is very often a matter of the speaker’s attitude (what linguists call ‘aspect’, how speakers view the actions they are referring to). What is it that is motivating someone to travel from ‘here’ to ‘there’? Perhaps ‘here’ feels alien, and the speaker needs to escape. At other times ‘here’ might represent comfort and familiarity. More intriquingly, the speaker might be torn or be going through a change in attitude. These are the situations that are likely to appeal to poets.

In 1821 Leitner captured the spirit of so many young people who feel constricted in their home environments and feel an urge to travel to distant lands (Drang in die Ferne, D 770). A young man brought up in a remote Alpine valley looks up at the clouds scurrying past and down at the river hurtling towards the sea, and he feels the need to go along with them:

Vaterlands Felsental

Wird mir zu eng, zu schmal;

Denn meiner Sehnsucht Traum

Findet darin nicht Raum.

My fatherland's valley enclosed by cliffs

Is becoming too narrow for me, too constricted;

For my dreams of longing

Cannot find any space within it.

Leitner, Drang in die Ferne D 770

There are countless such figures in the Schubert song texts, whose experience of longing and yearning for a better world make them dissatisfied with the here and now.

We should not forget those who see things differently, though. Lappe’s hermit listening to the sound of a cricket insists that he is totally contented with his situation. Perhaps this is just the voice of resigned old age, so distinct from Leitner’s impetuous youth.

O wie ich mir gefalle

In meiner stillen Ländlichkeit!

Was in dem Schwarm der lauten Welt

Das irre Herz gefesselt hält,

Gibt nicht Zufriedenheit.

Oh, I so much like being

In my quiet rural surroundings.

In the buzz of the loud world whatever

Has imprisoned the crazy heart

Gives no satisfaction.

Lappe, Der Einsame D 800

Goethe’s Auf dem See (D 543) captures a moment where perceptions and outlook change. The word ‘here’ becomes the axis of the poem and conveys something of the power of the new insight gained by the poet at a particular time and place: Lake Zürich on the morning of 15th June 1775.

The poet was 25 years old at the time, and he was in the company of the Stolberg brothers, who realised that it was exactly 25 years ago that Klopstock had written his famous Ode, Der Zürcher See. They decided to row across the lake and when they landed on the Au peninsula they recited Klopstock’s Ode, looking across the waters back towards the city and, in the other direction, towards the high Alps. Goethe’s Auf dem See (On the Lake) appears to be appended as a footnote to Klopstock’s text (it begins with Und – And!).

Goethe was in Switzerland because he had recently been propelled to unwelcome fame. His epistolary novel Die Leiden des Jungen Werthers had just been published and he found himself one of the most famous figures in Europe. His immediate reaction was to flee to Italy and to change career. He would become an artist. He would leave law and letters behind him as he established a new persona elsewhere. As he rode across Lake Zürich in June 1775 he caught his first glimpse of the Alps, beyond which lay Italy and his new life. It was then that he had some sort of epiphany. He did not need to go ‘there’ to renew himself. The mountains reflected in the lake showed him that he did not need to see them as a barrier. They are already approaching him in greeting as he contemplates their reflection in the lake. Indeed, he did not need to strive to any sort of world ‘beyond’ or ‘above’ this one. He comes to a realisation that his new project will involve a close analysis of nature itself. He can study the heavens (the sky) by looking at its reflection in this lake. Similarly he can look into the rocks of the mountains (geology) and explore the workings of plants as they grow (biology). Human beings and human experience are not separate from nature but a constituent part of it. It is all here.

Hier auch Lieb und Leben ist. / Here too there is love and life.

Und frische Nahrung, neues Blut

Saug ich aus freier Welt;

Wie ist Natur so hold und gut,

Die mich am Busen hält!

Die Welle wieget unsern Kahn

Im Rudertakt hinauf,

Und Berge, wolkig himmelan,

Begegnen unserm Lauf.

Aug, mein Aug, was sinkst du nieder?

Goldne Träume, kommt ihr wieder?

Weg, du Traum, so Gold du bist,

Hier auch Lieb und Leben ist.

Auf der Welle blinken

Tausend schwebende Sterne,

Weiche Nebel trinken

Rings die türmende Ferne;

Morgenwind umflügelt

Die beschattete Bucht,

Und im See bespiegelt

Sich die reifende Frucht.

And fresh nutrition, new blood,

I suck from this open world;

Nature is so beautiful and good,

Holding me to its breast!

The waves are rocking our boat

With the rhythm of the oars,

And mountains, in clouds reaching up to the sky,

Come to meet us as we make our way.

Eye, my eye, why are you sinking down?

Golden dreams, are you going to return?

Begone, dream! however golden you are;

Here too there is love and life.

Twinkling on the waves

Are a thousand hovering stars,

Gentle mists are drinking

Up the looming distance;

The morning wind is flying around

The shaded bay,

And mirrored in the lake

Is the ripening fruit.

Goethe, Auf dem See D 543

At the other extreme from Goethe’s acceptance of the ‘here and now’ are those poets who never feel that they can belong anywhere, who will always long for a different place and time. This appears at its most explicit in Ihr Grab (Her grave) by Engelhardt. Here the speaker points to his wife’s grave. He feels the gulf between ‘there’ (death) and ‘here’ (life) as an agonizing chasm.

Dort ist ihr Grab -

Die einst im Schmelz der Jugend glühte,

Dort fiel sie - dort - die schönste Blüte

Vom Baum des Lebens ab.

Dort ist ihr Grab -

Dort schläft sie unter jener Linde,

Ach, nimmer ich ihn wiederfinde

Den Trost, den sie mir gab.

Dort ist ihr Grab -

Vom Himmel kam sie, dass die Erde

Mir Glücklichen zum Himmel werde -

Und dort stieg sie hinab.

Dort ist ihr Grab -

Und dort in jenen stillen Hallen -

Bei ihr, lass ich mit Freuden fallen

Auch meinen Pilgerstab.

Her grave is over there -

She who once glowed with the lustre of youth,

Over there is where she fell - over there - the most beautiful blossom

To fall from the tree of life.

Her grave is over there -

She is sleeping over there, under that lime tree.

Oh! I shall never find it again

That comfort that she gave me!

Her grave is over there -

She came from heaven, so that earth

Would become heaven for me, lucky me -

And over there is where she climbed down.

Her grave is over there

And over there in those quiet halls -

Alongside her is where I shall joyfully drop

My pilgrim's staff too.

Engelhardt, Ihr Grab D 736

Many of the poems by Johann Mayrhofer, Schubert’s friend and room-mate, share this tragic approach to the human condition. He repeatedly uses the image of a river to represent his inner restlessness. Mayrhofer, like Schubert, lived his whole life in and around Vienna. He saw the Danube flow past his office every day towards a distant sea that he would never set eyes on. Like the river, he knew that he did not belong ‘here’.

Ist mir's doch, als sei mein Leben

An den schönen Strom gebunden.

Hab ich Frohes nicht an seinem Ufer,

Und Betrübtes hier empfunden!

Ja du gleichest meiner Seele;

Manchmahl grün und glatt gestaltet;

Und zu Zeiten, herrschen Stürme,

Schäumend, unruhvoll, gefaltet.

Fließest zu dem fernen Meere,

Darfst allda nicht heimisch werden;

Mich drängt's auch in mildre Lande,

Finde nicht das Glück auf Erden.

But it appears to me as if my life

Is bound up with this beautiful river.

Is it not the case that on its banks I have known something of joy

And I have experienced distress here?

Yes, you are similar to my soul;

Sometimes green and with a smooth surface,

And at other times, when storms dominate,

Foaming, disturbed, furrowed.

You are flowing towards the distant sea,

Unable to feel that you belong anywhere.

I too am being driven to a more gentle land -

I cannot find happiness on earth.

Mayrhofer, Am Strome D 539

Schiller also uses the image of a river flowing eastwards towards the open sea in Der Pilgrim, but in this case he has no illusions that ‘there’ will ever become ‘here’. Humans might try their best to bridge the gaps between desire and fulfilment, but the goal will always remain out of reach.

Noch in meines Lebens Lenze

War ich, und ich wandert' aus,

Und der Jugend frohe Tänze

Ließ ich in des Vaters Haus.

All mein Erbtheil, meine Habe

Warf ich fröhlich glaubend hin,

Und am leichten Pilgerstabe

Zog ich fort mit Kindersinn.

Denn mich trieb ein mächtig Hoffen

Und ein dunkles Glaubenswort,

Wandle, rief's, der Weg ist offen,

Immer nach dem Aufgang fort.

Bis zu einer goldnen Pforten

Du gelangst, da gehst du ein,

Denn das Irdische wird dorten

Ewig unvergänglich sein.

Abend ward's und wurde Morgen,

Nimmer, nimmer stand ich still,

Aber immer blieb's verborgen,

Was ich suche, was ich will.

Berge lagen mir im Wege,

Ströme hemmten meinen Fuß,

Über Schlünde baut' ich Stege,

Brücken durch den wilden Fluss.

Und zu eines Stroms Gestaden

Kam ich, der nach Morgen floss,

Froh vertrauend seinem Faden

Warf ich mich in seinen Schoß.

Hin zu einem großen Meere

Trieb mich seiner Wellen Spiel,

Vor mir liegt's in weiter Leere,

Näher bin ich nicht dem Ziel.

Ach kein Weg will dahin führen,

Ach der Himmel über mir

Will die Erde nicht berühren,

Und das Dort ist niemals Hier.

I was still in the springtime of my life

When I set out to travel,

And the happy dances of youth -

I left them behind in my father's house.

All of my inheritance, everything I had

I threw it away happily and trustingly,

And I took up a light pilgrim's staff

And set off with a childlike attitude.

For I was being driven by a powerful hope

And a dark saying that encouraged faith:

Wander off, it called, the path is open,

Always leading towards the rising sun.

Until you reach a golden gate,

When you get there, go in,

Because what is earthly will there

Become eternal, immortal.

It was evening and it became morning

I never stood still, never,

But it always remained hidden,

The thing I was looking for, what I wanted.

Mountains lay in my way,

Streams hemmed in my feet,

I built footbridges across crevices,

I built bridges over the savage river.

And I came to the bank of a stream

That was flowing to the East, I came there

And happily trusting its current

I threw myself into its lap.

I was taken off to a great ocean,

The play of its waves carried me along,

Lying in front of me is a broad expanse,

I am no nearer to my goal.

Oh, no path is going to lead there,

Oh the sky above me

Is not going to touch the earth,

And 'there' is never 'here'.

Schiller, Der Pilgrim D 794

☙

Descendant of:

SPACE (location) REALITY AND UNREALITYTexts with this theme:

- Schäfers Klagelied, D 121 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Genügsamkeit, D 143 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Nähe des Geliebten, D 162 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Die Sterne (Was funkelt ihr so mild mich an), D 176 (Johann Georg Fellinger)

- Naturgenuss, D 188, D 422 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Die Erscheinung, D 229 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Hin und wieder fliegen Pfeile, D 239/3 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Mignon (So lasst mich scheinen), D 469, D 727, D 877/3 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Wanderer (Ich komme vom Gebirge her), D 489 (Georg Philipp Schmidt)

- Fahrt zum Hades, D 526 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Schlaflied, D 527 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Am Strome, D 539 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Memnon, D 541 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Auf dem See, D 543 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Ganymed, D 544 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Atys, D 585 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Der Alpenjäger, D 588 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Das Abendrot (Du heilig, glühend Abendrot!), D 627 (Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber)

- Die Sternennächte, D 670 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Morgenlied (Eh die Sonne früh aufersteht), D 685 (Friedrich Ludwig Zacharias Werner)

- Nachthymne, D 687 (Friedrich Leopold von Hardenberg (Novalis))

- Suleika II, D 717 (Marianne von Willemer)

- Ihr Grab, D 736 (Karl August Engelhardt)

- Selige Welt, D 743 (Johann Chrysostomus Senn)

- Drang in die Ferne, D 770 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Der Pilgrim, D 794 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Widerspruch, D 865 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Im Freien, D 880 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Auf dem Strom, D 943 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- Abschied, D 957/7 (Ludwig Rellstab)