Longing by Hans-Dieter Gelfert

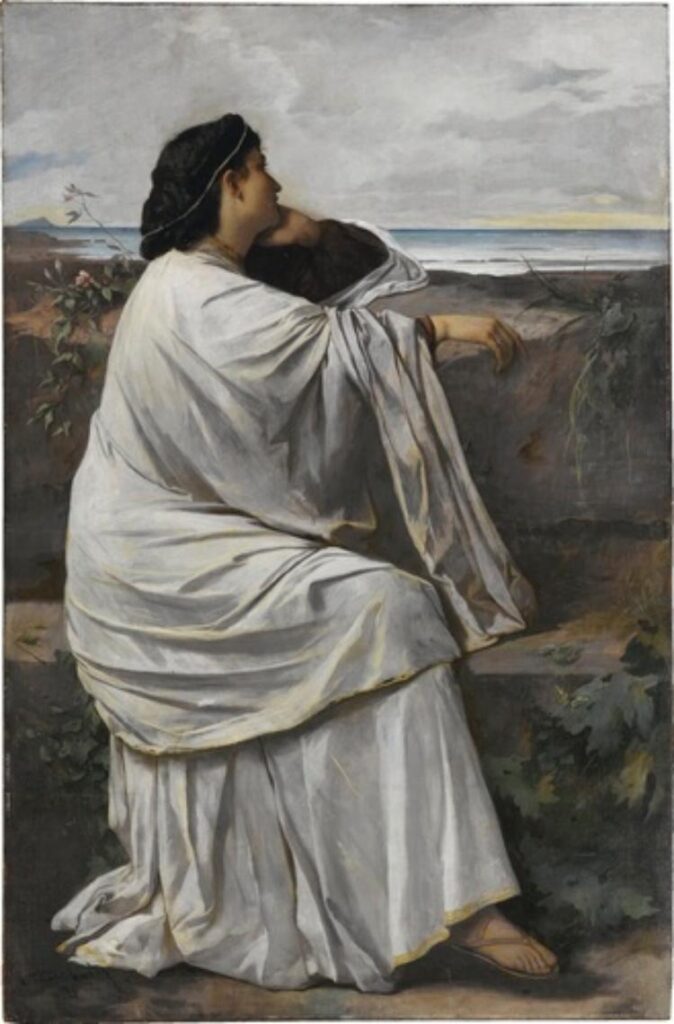

All human beings probably long now and again (or all the time) to be in a state that is better than the status quo. This is the basis of all the concepts of ‘beyond’ in religion and religion-like philosophies. Even in the here and now people long for a better world, making it possible to distinguish between specific cultures based on the intensity of longing in them. A simple comparison between a large anthology of German lyrics and a similarly sized collection of English or French verse will show that longing plays a more significant role in German poems. Even Goethe, who unlike most of his fellow poets stood firmly with both feet planted in the here and now, wrote poems that made longing almost proverbial. ‘Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt, / Weiß, was ich leide!’ (‘Only someone who is familiar with longing / Can know what I am suffering!’), sings Mignon in Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre; and another, equally famous poem bears the title, ‘Selige Sehnsucht’ (Blessed Longing). In the Romantic movement longing finally became the prevailing state of mind. It is not just a recurrent concern in poetry. In painting too the image of looking longingly out of a window became a standard motif. On the whole, this is an undefined longing, looking out into the distance into the freedom or infinity of the world, but there are also concrete yearnings, above all for Italy, which Germans continue to feel. Goethe himself felt this so acutely that he gave in to it and set off on a long journey to Italy. He presents his Iphigenia as a woman longing for her homeland, ‘searching for the land of the Greeks with her soul’. This is how Anselm Feuerbach painted her in an image which became an icon of the German longing for Greece. There are also many folksongs that feature longing, with spring, home and the distant beloved serving as the typical objects of desire.

Given the obsessive way in which this feeling is invoked, one gains the impression that this sense of yearning for a goal offers more satisfaction for Germans than does attaining it. We know that Lessing valued the search for truth more highly than possession of it. But a search presupposes longing. Within philosophy itself Kant’s ‘postulates’ and Hegel’s ‘speculation’ both involve an element of longing. There can be no doubt that the art in which longing is most fully expressed is music, for in essence the enjoyment of music consists of arousing a longing in the listener, who yearns for satisfaction yet who also wants the moment of satisfaction to be postponed for as long as possible. Once this is made clear, it becomes apparent that it is no far-fetched assumption to regard music, that most German of all the arts, as the expression of this general German longing.

Anyone who traces the motif of longing through German culture in the last three centuries will understand why it is that the Germans first paid attention to the call of daydreams, which eventually fell victim to a political dream, which then turned into a nightmare. When Thomas Mann was asked to contribute a quotation on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the establishment of the Weimar Republic in 1924, he declined to do so in a direct way and instead proposed a passage from Hölderlin’s Empedokles, which in a veiled poetic way refers to the end of kings and the arrival of democracy. Thomas Mann’s comment on Hölderlin’s Utopia was as follows:

“The way that lonely poets dreamt of Greece, of a society that is sacred and free, of a new covenant that is established with deep and courageous rejuvenation and sealed with law, all of that is a dream that has emerged from all our longings, out of the ‘German soul’, which is something different from what the Romantics envisioned. It is not homesickness or longing for the Linden tree, but a desire for sacrifice, for annihilation, for new birth and for eternal becoming.”

All of this sends a shiver down the spine, because the self-same readiness for sacrifice and mystical longing for annihilatition cum rebirth is something that the National Socialists mobilised in order to bring about the holy society of the ‘Volk’ and establish a ‘greater German Empire’.

from Hans-Dieter Gelfert, Was ist deutsch? Wie die Deutschen wurden, was sie sind (2005) pp. 58 – 61 English translation by Malcolm Wren

Descendant of:

EMOTIONS ABSTRACT CONCEPTS REALITY AND UNREALITYTexts with this theme:

- Sehnsucht (Was zieht mir das Herz so?), D 123 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Genügsamkeit, D 143 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Die Erwartung, D 159 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Sängers Morgenlied, D 163, D 165 (Theodor Körner)

- Liebesrausch, D 164, D 179 (Theodor Körner)

- Der Morgenstern, D 172, D 203 (Theodor Körner)

- Das war ich, D 174, D deest (Theodor Körner)

- Sehnsucht der Liebe, D 180 (Theodor Körner)

- Die erste Liebe, D 182 (Johann Georg Fellinger)

- Von Ida, D 228 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Die Erscheinung, D 229 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Die Täuschung, D 230 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Das Sehnen, D 231 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Abends unter der Linde, D 235, D 237 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Die Mondnacht, D 238 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Alles um Liebe, D 241 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Totenkranz für ein Kind, D 275 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Sehnsucht (Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt), D 310, D 359, D 481, D 656, D 877/1, D 877/4 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Hektors Abschied, D 312 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Nachtgesang (Tiefe Feier schauert um die Welt), D 314 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Luisens Antwort, D 319 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Mignon (Kennst du das Land?), D 321 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Die drei Sänger, D 329 (Johann Friedrich Ludwig Bobrik)

- Der Entfernten, D 331, D 350 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- An Chloen, D 363 (Johann Peter Uz)

- An die Harmonie, D 394 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Lebens-Melodien, D 395 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Ritter Toggenburg, 397 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Abschied von der Harfe, D 406 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Die verfehlte Stunde, D 409 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Stimme der Liebe, D 412 (Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Das Heimweh, D 456 (Karl Gottfried Theodor Winkler)

- An den Mond (Was schauest du so hell), D 468 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Der Sänger am Felsen, D 482 (Caroline Pichler)

- Der Wanderer (Ich komme vom Gebirge her), D 489 (Georg Philipp Schmidt)

- Lebenslied, D 508, D Anh. I, 23 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Leiden der Trennung, D 509 (Pietro Metastasio and Heinrich Joseph von Collin)

- Nur wer die Liebe kennt, D 513A (Friedrich Ludwig Zacharias Werner)

- Der Flug der Zeit, D 515 (Ludwig (Lajos) Graf Széchényi von Sárvári-Felsö-Vidék)

- Sehnsucht (Der Lerche wolkennahe Lieder), D 516 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die Blumensprache, D 519 (Anonymous / Unknown writer)

- Memnon, D 541 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Ganymed, D 544 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Strom, D 565 (Anonymous / Unknown writer)

- Vollendung, D 579A (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Atys, D 585 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Der Alpenjäger, D 588 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Die Geselligkeit, D 609 (Johann Carl Unger)

- Auf der Riesenkoppe, D 611 (Theodor Körner)

- An den Mond in einer Herbstnacht, D 614 (Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber)

- Einsamkeit, D 620 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die Berge, D 634 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Widerschein, D 639, D 949 (Franz von Schlechta)

- Abend, D 645 (Johann Ludwig Tieck)

- Himmelsfunken, D 651 (Johann Peter Silbert)

- Hymne I, D 659 (Friedrich Leopold von Hardenberg (Novalis))

- Lob der Tränen, D 711 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Suleika II, D 717 (Marianne von Willemer)

- Geheimes, D 719 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Die Nachtigall (Bescheiden verborgen), D 724 (Johann Carl Unger)

- Der Blumen Schmerz, D 731 (Johann (János) Nepomuk Josef Graf Mailáth)

- Sei mir gegrüßt, D 741 (Friedrich Rückert)

- Schatzgräbers Begehr, D 761 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Drang in die Ferne, D 770 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Der Zwerg, D 771 (Matthäus Karl von Collin)

- Du bist die Ruh, D 776 (Friedrich Rückert)

- Viola, D 786 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Vergissmeinnicht, D 792 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Pause, D 795/12 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Der Sieg, D 805 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die junge Nonne, D 828 (Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Des Sängers Habe, D 832 (Franz von Schlechta)

- Im Walde (Ich wandre über Berg und Tal), D 834 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Totengräbers Heimwehe, D 842 (Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Das Heimweh, D 851 (Johann Ladislaus Pyrker von Felső-Eör )

- Auf der Bruck, D 853 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Wiedersehn, D 855 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Abendlied für die Entfernte, D 856 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Um Mitternacht, D 862 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Widerspruch, D 865 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Mondenschein, D 875 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Sehnsucht (Die Scheibe friert), D 879 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Lebensmut, D 883 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Wolke und Quelle, D 896B (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Wasserflut, D 911/6 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Heimliches Lieben, D 922 (Caroline Louise Hempel)

- Auf dem Strom, D 943 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- Kriegers Ahnung, D 957/2 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- Frühlingssehnsucht, D 957/3 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- Ständchen, D 957/4 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- In der Ferne, D 957/6 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- Am Meer, D 957/12 (Heinrich Heine)

- Der Hirt auf dem Felsen, D 965 (Wilhelm Müller and Karl August Varnhagen von Ense)

- Die Taubenpost, D 965A (Johann Gabriel Seidl)