‘The end of the line’ or ‘A stop on the way’

Du heil'ge Nacht,

Bald ist's vollbracht,

Bald schlaf ich ihn,

Den langen Schlummer,

Der mich erlöst

Von allem Kummer.

"Oh holy night!

It will soon be fulfilled.

I shall soon be sleeping

That long sleep

Which will release

Me from all care."

Mayrhofer, Nachtstück D 672

The minstrel speaking here is using one of the basic ‘metaphors we live by’, one of those essential structures of human thought that is so fundamental to our perception of the world that we stop noticing it. As the minstrel sings his swan-song, he declares that he is about to enter the long sleep that will end his misery. He enters the sacred domain of night.

Of course, we tell ourselves, poets use the image of ‘night’ to refer to ‘death’, but we overlook something crucial. Different poems and different contexts will emphasise different aspects of ‘death’ and of ‘night’. In this case, the full context of Mayrhofer’s narrative shows that the night that is arriving for this singer will never end. Death is ‘The End’ in this case.

Wenn über Berge sich der Nebel breitet,

Und Luna mit Gewölken kämpft,

So nimmt der Alte seine Harfe und schreitet

Und singt waldeinwärts und gedämpft:

Du heil'ge Nacht,

Bald ist's vollbracht,

Bald schlaf ich ihn,

Den langen Schlummer,

Der mich erlöst

Von allem Kummer.

Die grünen Bäume rauschen dann:

Schlaf süß, du guter alter Mann;

Die Gräser lispeln wankend fort:

Wir decken seinen Ruheort;

Und mancher liebe Vogel ruft:

O lasst ihn ruhn in Rasengruft.

Der Alte horcht, der Alte schweigt,

Der Tod hat sich zu ihm geneigt.

When the mist spreads across the mountains

And Luna goes into battle against the clouds,

That is when the old man takes his harp and steps forwards,

And turning towards the forest sings in muffled tones:

"Oh holy night!

It will soon be fulfilled.

I shall soon be sleeping

That long sleep

Which will release

Me from all care."

The green trees then rustle,

Sleep sweetly, good old man;

The blades of grass whisper as they sway,

We shall cover his place of rest;

And many a dear bird cries out,

Oh let him rest in this trench in the turf! -

The old man pays attention, the old man remains silent -

Death has bent down towards him.

Mayrhofer, Nachtstück D 672

We can contrast this with a poem written at around the same time (1818) and in the same place (Vienna) by Johann Petrus Silbert, Abendbilder (Evening pictures), also set by Schubert (D 650) in 1819. Here the lesson the writer takes from the metaphor of ‘night’ is that it always precedes day. He therefore concludes that death will be followed by resurrection.

Still beginnt's im Hain zu tauen;

Ruhig webt der Dämmrung Grauen

Durch die Glut

Sanfter Flut,

Durch das Grün umbüschter Auen,

So die trunk'nen Blicke schauen.

Sieh, der Raben Nachtgefieder

Rauscht auf ferne Eichen nieder.

Balsamduft

Haucht die Luft;

Philomelens Zauberlieder

Hallet zart die Echo wieder.

Horch! des Abendglöckleins Töne

Mahnen ernst der Erde Söhne,

Dass ihr Herz

Himmelwärts,

Sinnend ob der Heimat Schöne,

Sich des Erdentands entwöhne.

Durch der hohen Wolken Riegel

Funkeln tausend Himmelssiegel,

Lunas Bild

Streuet mild

In der Fluten klarem Spiegel,

Schimmernd Gold auf Flur und Hügel.

Von des Vollmonds Widerscheine

Blitzet das bemooste, kleine

Kirchendach.

Aber ach,

Ringsum decken Leichensteine

Der Entschlummerten Gebein.

Ruht, o Traute! von den Wehen,

Bis beim großen Auferstehen

Aus der Nacht

Gottes Macht

Einst uns ruft, in seiner Höhen

Ew'ge Wonnen einzugehen.

Dew is quietly beginning to settle in the grove;

The grey of dusk is calmly weaving its way

Through the glow

On the gentle waters,

Through the green of the meadows surrounded by bushes;

Thus it is that our drunken gaze beholds it.

Look! The nocturnal feathers of the ravens

Coming down cause a rustling in the distant oaks. -

The scent of balsam

Can be smelt in the air;

Philomel's magical songs

Resound tenderly in the echo.

Listen! The notes of the evening bell

Are sending a powerful reminder to the sons of earth

That their hearts

Should turn heavenwards,

As they reflect on the beauty of home

And the need to break their attachment to the fripperies of earth.

Through the canopy of the high clouds

A thousand heavenly seals are glittering,

The image of Luna

Is gently being scattered

Over the clear mirror of the flooding waters,

Shining gold on the fields and hills.

From the reflection of the full moon

Flashes the moss-covered small

Roof of the church.

But oh!

All around, tombstones cover

The bones of those who have fallen asleep.

Dear friends, take a rest after your sorrows,

Until at the great resurrection,

Out of the night,

God's power

Eventually calls us up to his heights,

To enter into eternal bliss.

Silbert, Abendbilder D 650

These two very different poets, the melancholic (and suicidally inclined) Mayrhofer and the pious theologian Silbert, use identical images to achieve divergent effects: the moon (Luna) is either in battle with the clouds that are trying to obstruct its light or it is gently pouring its comforting beams over the landscape; the birds either tell the dying man to lie down and die, or they join in with the evening bells to encourage us to turn our thoughts towards heaven; the general direction is either downwards (into the enclosed grave) or upwards (as we are released from the site of this temporary rest).

‘Terror’ or ‘Solace’

Night triggers different associations and connotations depending on people’s psychological states and their character traits. Some texts (not just the obvious ghost stories) express terror and horror while others present the arrival of night as an offer of solace and comfort.

The persona faced with his own Doppelgänger in Heine’s famous poem (D 957/13) is suffering from a deep psychological trauma. The agony with which he is confronted has already tormented him for ‘so many nights’ (So manche Nacht):

Still ist die Nacht, es ruhen die Gassen,

In diesem Hause wohnte mein Schatz,

Sie hat schon längst die Stadt verlassen,

Doch steht noch das Haus auf demselben Platz.

Da steht auch ein Mensch und starrt in die Höhe

Und ringt die Hände vor Schmerzensgewalt;

Mir graust es, wenn ich sein Antlitz sehe,

Der Mond zeigt mir meine eigne Gestalt.

Du Doppelgänger, du bleicher Geselle,

Was äffst du nach mein Liebesleid,

Das mich gequält auf dieser Stelle

So manche Nacht, in alter Zeit?

The night is quiet, the alleyways are at rest,

My treasure used to live in this house;

She left the town long ago,

But the house is still standing in the same place.

There is a man standing there too and he is staring up high,

And he is wringing his hands as a result of overwhelming pain;

I feel terrified when I see his face, -

The moon shows me my own form.

You doppelgänger, you pale guy!

Why are you aping my love agony,

The pain that tormented me on this spot,

So many nights in the old days?

Heine, Der Doppelgänger D 957/13

A text by Jacobi expresses the pain and ‘deep anxiety’ of another character at night. His only hope is that a more beautiful, kinder night will follow. The only happiness on offer is that of the grave, eternal night:

Todesstille deckt das Tal

Bei des Mondes falbem Strahl!

Winde flüstern dumpf und bang

In des Wächters Nachtgesang.

Leiser, dumpfer tönt es hier

In der bangen Seele mir,

Nimmt den Strahl der Hoffnung fort,

Wie den Mond die Wolke dort.

Hüllt, ihr Wolken, hüllt den Schein

Immer tiefer, tiefer ein!

Vor ihm bergen will mein Herz

Seinen tiefen, tiefen Schmerz.

Nennen soll ihn nicht mein Mund:

Keine Träne mach ihn kund;

Senken soll man ihn hinab

Einst mit mir ins kühle Grab.

O der schönen langen Nacht,

Wo nicht Erdenliebe lacht,

Wo verlassne Treue nicht

Ihren Kranz von Dornen flicht!

An des Todes milder Hand

Geht der Weg ins Vaterland;

Dort ist Liebe sonder Pein;

Selig, selig werd ich sein.

A deathly silence is covering the valley

In the pale moonlight;

Winds are whispering, muffled and anxious,

In the watchman's night song.

It resounds here, more gentle, more muffled,

In my anxious soul,

It takes away the ray of hope

As the cloud up there removes the moon.

Wrap it, clouds, wrap the glow

Up, ever deeper, deeper!

My heart wants to hide from it

Its deep, deep pain.

My mouth will not name it;

No tears will acknowledge it;

It should be buried

Along with me in the cool grave.

Oh, that beautiful long night

Where no earthly love laughs,

Where faithlessness does not

Construct a wreath of thorns!

In the gentle hand of death

The path leads into the fatherland;

There, there is love without agony;

I shall be happy, happy.

Jacobi, In der Mitternacht D 464

Goethe’s Mignon finds that night offers no consolation for all of the agonies she has to suffer by day:

Kaum will mir die Nacht noch frommen,

Denn die Träume selber kommen

Nun in trauriger Gestalt,

Und ich fühle dieser Schmerzen,

Still im Herzen,

Heimlich bildende Gewalt.

Night will barely console me

For even dreams come

Only in a sad form,

And I feel this pain,

Silent in the heart,

Secret, growing ever more powerful.

Goethe, An Mignon D 161

For others, though, dreams and night offer comfort. What is uncomfortable is having to wake up and face the day.

Heil'ge Nacht, du sinkest nieder;

Nieder wallen auch die Träume,

Wie dein Mondlicht durch die Räume,

Durch der Menschen stille Brust;

Die belauschen sie mit Lust,

Rufen, wenn der Tag erwacht:

Kehre wieder heil'ge Nacht,

Holde Träume kehret wieder.

Holy night, you are sinking down;

Dreams too are floating down,

Like your moonlight through the expanses of space,

Through the silent breasts of human beings,

Who eavesdrop on them with pleasure;

They call, when day awakes:

Come back, holy night,

Beauteous dreams, come back again.

von Collin, Nacht und Träume D 827

There is no clear distinction between consolation and escapism, of course, but many of the poems that Schubert set to music stress the value of looking at the night sky to find a comforting sense of perspective.

O Ida, wenn die Schwermut

Dein sanftes Auge hüllt,

Wenn dir die Welt mit Wermut

Den Lebensbecher füllt;

So geh hinaus im Dunkeln

Und sieh die Sterne funkeln,

Und leiser wird dein Schmerz,

Und freier schlägt dein Herz.

Oh Ida, when melancholy

Shrouds your gentle eyes,

When the world offers wormwood

And fills the beaker of your life with it,

Just go out into the darkness,

And watch the stars glowing,

And your pain will be eased,

And your heart will beat more freely.

Kosegarten, Die Sterne D 313

In monderhellten Nächten,

Mit dem Geschick zu rechten,

Hat diese Brust verlernt.

Der Himmel, reich gestirnt,

Umwoget mich mit Frieden,

Da denk ich, auch hienieden

Gedeihet manche Blume.

Und frischer schaut der stumme,

Sonst trübe Blick hinauf

Zum ew'gen Sternenlauf.

Auf ihnen bluten Herzen,

Auf ihnen quälen Schmerzen,

Sie aber strahlen heiter.

So schließ ich selig weiter,

Auch unsre kleine Erde,

Voll Misston und Gefährde,

Sich als ein heiter Licht

In's Diadem verflicht,

So werden Sterne

Durch die Ferne.

On moonlit nights

Trying to challenge fate

Is something that my breast has given up.

The sky, richly star spangled,

Swirls around me in peace.

Then I think: Even down here

Many flowers flourish;

And, more cheerfully I turn my silent

(Though imprecise) gaze upwards

Towards the course of the eternal stars.

On them hearts bleed,

On them pain is suffered -

But they shine cheerfully.

Thus, contented I go on to conclude:

Our small earth, too,

Full of discord and danger,

Appears as a cheerful light

Woven into the diadem.

That is what stars become

Across a distance!

Mayrhofer, Die Sternennächte D 670

The eye in the sky

A similar type of detachment is possible when night reminds us of our physical or emotional separation from others. The simple act of looking up at the moon can remind us that absent friends can see it too. This is usually phrased more poetically – the moon (an eye or a face) is actively looking at people we cannot see, forming a triangular gaze.

Leitner’s Drang in die Ferne (Urge to go far away) gives voice to a young man who finds his mountain home too restrictive and tries to persuade his parents to allow him to travel. He reassures them that the moon and the stars will be keeping an eye on him if he leaves:

Lasst mich! ich muss, ich muss

Fordern den Scheidekuss.

Vater und Mutter mein,

Müsset nicht böse sein:

Hab euch ja herzlich lieb,

Aber ein wilder Trieb

Jagt mich waldein, waldaus,

Weit von dem Vaterhaus.

Sorgt nicht durch welches Land

Einsam mein Weg sich wand.

Monden- und Sternenschein

Leuchtet auch dort hinein.

Let me go! I have to, I must,

Request a farewell kiss.

Dear father and mother,

You mustn't be angry:

I really love you with all my heart

Yet a savage instinct

Is chasing me into the forest and beyond,

Far from my paternal home.

Do not worry about which land

My solitary path is taking me towards,

The light of the moon and the stars

Will be shining down even there.

von Leitner, Drang in die Ferne D 770

Schreiber is even more evocative in An den Mond in einer Herbstnacht. Here the moon has a friendly face (it has always been difficult for human beings not to anthropomorphise the moon) and its gaze serves to connect the speaker to friends who are distant in time and space.

Freundlich ist dein Antlitz,

Sohn des Himmels!

Leis sind deine Tritte

Durch des Äthers Wüste,

Holder Nachtgefährte.

Dein Schimmer ist sanft und erquickend

Wie das Wort des Trostes

Von des Freundes Lippe,

Wenn ein schrecklicher Geier

An der Seele nagt.

Manche Träne siehst du,

Siehst so manches Lächeln,

Hörst der Liebe trauliches Geflüster,

Leuchtest ihr auf stillem Pfade,

Hoffnung schwebt auf deinem Strahle

Herab zum stillen Dulder,

Der verlassen geht auf bedorntem Weg.

Du siehst auch meine Freunde,

Zerstreut in fernen Landen;

Du gießest deinen Schimmer

Auch auf die frohen Hügel,

Wo ich oft als Knabe hüpfte,

Wo oft bei deinem Lächeln

Ein unbekanntes Sehnen

Mein junges Herz ergriff.

Du blickst auch auf die Stätte,

Wo meine Lieben ruhn,

Wo der Tau fällt auf ihr Grab,

Und die Gräser drüber wehn

In dem Abendhauche.

Your face is friendly,

Son of heaven!

Your footsteps are light

As they cross the deserted ether,

Beautiful nocturnal companion.

Your shimmering light is gentle and refreshing,

Like the word of reassurance

From the lips of a friend,

When a terrible vulture

Is gnawing at your soul.

You can see many a tear,

You can see so much smiling,

You can hear the intimate whispering of lovers

And you shed light on their quiet footpath,

Hope floats on your beams of light

Coming down to those who suffer in silence,

Those who, having been abandoned, walk along a thorny path.

You can also see my friends,

Scattered in distant countries;

You pour your shimmering light

Even onto the happy hills

Where I often used to jump around as a boy,

Where frequently, as you smiled,

An unfamiliar longing

Took hold of my heart.

You also look down on the places

Where my loved ones are resting,

Where the dew falls on their grave,

On top of which the grass sways

In the breath of evening.

Schreiber, An den Mond in einer Herbstnacht D 614

Then there is Goethe’s incomparable masterpiece An den Mond, which uses similar imagery but with greater ambition. It begins with the image of the moon as an eye, perhaps even an eye that has been crying since the moon emerges from mist. It is clearly an eye that is actively looking, and the looking is emotional and caring. The writer sees the moon as a friend, almost certainly because he is feeling abandoned and isolated. He is conscious of having alienated a good friend and is having to come to terms with hostile glances and unsympathetic audiences.

What he has lost is a connection that ‘paces around in the labyrinth of the breast at night’. The poem weaves together strands of imagery about light and water, flow and connection to tell us about isolation. The night here is the darkness of our emotional immaturity and our inability to look on others with sympathy and establish meaningful connections.

Füllest wieder Busch und Tal

Still mit Nebelglanz,

Lösest endlich auch einmal

Meine Seele ganz;

Breitest über mein Gefild

Lindernd deinen Blick,

Wie des Freundes Auge mild

Über mein Geschick.

Jeden Nachklang fühlt mein Herz

Froh- und trüber Zeit,

Wandle zwischen Freud und Schmerz

In der Einsamkeit.

Fließe, fließe, lieber Fluß,

Nimmer werd ich froh,

So verrauschte Scherz und Kuss,

Und die Treue so.

Ich besaß es doch einmal,

Was so köstlich ist,

Dass man doch zu seiner Qual

Nimmer es vergißt.

Rausche, Fluss, das Tal entlang,

Ohne Rast und Ruh,

Rausche, flüstre meinem Sang

Melodien zu,

Wenn du in der Winternacht

Wütend überschwillst,

Oder um die Frühlingspracht

Junger Knospen quillst.

Selig, wer sich vor der Welt

Ohne Hass verschließt,

Einen Freund am Busen hält

Und mit dem genießt,

Was, von Menschen nicht gewusst,

Oder nicht bedacht,

Durch das Labyrinth der Brust

Wandelt in der Nacht.

Once again you fill the woodland and valley

With a quiet, misty glow,

And in the end you also manage to release

My soul completely.

Over my realm you spread

Your soothing glance,

Like the gentle eyes of a friend

Watching over my fate.

My heart feels each echo

Of truly happy and gloomy times,

I dither between joy and pain

In this solitude.

Flow on, flow on, dear river!

I shall never be truly happy;

In such a way playfulness and kisses have faded away,

As has faithfulness.

However, I did once possess it,

That which is so valuable!

It is something so agonizing that

It can never be forgotten.

Roar away along the valley, river,

Without a break, without rest,

Roar on, accompany my song by whispering

Melodies to go with it,

When, on a winter's night,

You overflow in fury

Or, around the majesty of spring,

You swell young buds.

Blessed is anyone who, avoiding the world,

Locks themselves away without hatred

And holds a friend to their bosom

And with that person enjoys

That which, unknown to humans

Or not even imagined by them,

Through the labyrinth of the breast

Paces around during the night.

Goethe, An den Mond D 259, D 296

Are you lonesome tonight?

The flip side of the ability to look at the moon as a means of connecting us to others (be they absent friends, lovers or the dead) is that it also intensifies the sense of isolation and loneliness which so many people feel at night. Schulze, the obsessive lover of an unattainable woman, became intensely aware of this at midnight on 5th March 1815:

Keine Stimme hör ich schallen,

Keinen Schritt auf dunkler Bahn,

Selbst der Himmel hat die schönen

Hellen Äuglein zugetan.

Ich nur wache, süßes Leben,

Schaue sehnend in die Nacht,

Bis dein Stern in öder Ferne

Lieblich leuchtend mir erwacht.

I can hear no voice resounding,

No footsteps on the dark pathway;

Even the sky has

Closed its beautiful bright eyes.

Only I am awake, sweet life,

I am looking longingly out into the night,

Until your star in the barren distance

Wakes me up lovingly with its light.

Schulze, Um Mitternacht D 862

The loneliness in Kosegarten’s Das Sehnen (Longing) is much more than unrequited love, though. Night-time reinforces the speaker’s lack of connection on all levels, aesthetic, social and emotional.

Wehmut, die mich hüllt,

Welche Gottheit stillt

Mein unendlich Sehnen?

Die ihr meine Wimper nässt,

Namenlosen Gram entpresst,

Fließet, fließet Tränen.

Mond, der lieb und traut

In mein Fenster schaut,

Sage, was mir fehle?

Sterne, die ihr droben blinkt,

Holden Gruß mir freundlich winkt,

Nennt mir, was mich quäle.

Leise Schauer wehn,

Süßes Liebesflehn

Girrt um mich im Düstern.

Rosen- und Violenduft

Würzen rings die Zauberluft.

Holde Stimmen flüstern.

In die Ferne strebt,

Wie auf Flügeln schwebt

Mein erhöhtes Wesen.

Fremder Zug, geheime Kraft,

Namenlose Leidenschaft,

Lass, ach lass genesen.

Ängstender beklemmt

Mich die Wehmut, hemmt

Atem mir und Rede.

Einsam schmachten, o der Pein!

O des Grams, allein zu sein

In des Lebens Öde.

Ist denn ach kein Arm,

Der in Freud und Harm

Liebend mich umschlösse?

Ist denn ach kein fühlend Herz,

Keines, drin in Lust und Schmerz

Meines sich ergösse?

Die ihr einsam klagt,

Einsam, wenn es tagt,

Einsam wenn es nachtet,

Ungeströstet ach, verächzt

Ihr das holde Dasein, lechzt,

Schmachtet und verschmachtet.

How sorrow envelops me!

What divinity will calm

My endless longing?

As you dampen my eyelids

Oppressed with nameless pain

Flow, flow, you tears!

Moon, as you lovingly and intimately

Look into my window,

Tell me, what am I lacking?

Stars, gleaming up there,

Gesturing to me with a beauteous greeting,

Name what it is that is disturbing me!

Gentle shudders cause pain,

Sweet pleadings of love can be heard

Cooing around me in darkness.

The scents of roses and violets

Add spice to the magical air.

Beautiful voices whisper.

Struggling in the distance,

As if hovering on wings,

Is my heightened being.

Alien pull, secret power,

Nameless suffering,

Oh let me, let me recover!

More anxiously oppressed

As I am by sorrow, I have difficulty

Breathing and speaking.

Languishing alone, oh what pain!

Oh the grief of being alone

In the barrenness of life.

So is there then no arm

Which in joy and affliction

Will embrace me with love?

So is there then no feeling heart,

Noone who, in pleasure or pain,

Will take delight in me?

You who lament alone,

Alone when day breaks,

Alone when night sets in,

Uncomforted, oh, you scorn

This beautiful existence, you pant,

Languishing and parched.

Kosegarten, Das Sehnen D231

Here, night offers no comfort, no solace. The stars do not twinkle with the promise of love. The moonlight brings no companionship.

We can contrast this with other poems, such as Leitner’s Der Winterabend, where the moonlight comes through the window but is treated as a welcome guest making a late evening visit.

Ist gar ein stiller, ein lieber Besuch,

Macht mir gar keine Unruh im Haus,

Will er bleiben, so hat er Ort,

Freut's ihn nimmer, so geht er fort.

It is really a quiet, a dear visit,

Making no disturbance in the house.

If he wants to stay, there is a place for him,

If he is no longer enjoying it, then he leaves.

von Leitner, Der Winterabend D 938

The tone of these two ‘nocturnal’ texts is clear and unambiguous: Kosegarten is writing about loneliness and Leitner about sociability. What are we to make of Lappe’s Der Einsame (The loner), though? The speaker here says that he is not ‘alone’ because he can hear the cricket on the hearth at night, but perhaps he protests too much. This person might not be alone, but, as night falls, he could well be ‘lonesome’ or even ‘lonely’. He may be a recluse, but was that a voluntary choice?

Wann meine Grillen schwirren,

Bei Nacht, am spät erwärmten Herd,

Dann sitz ich, mit vergnügtem Sinn

Vertraulich zu der Flamme hin,

So leicht, so unbeschwert.

Ein trautes stilles Stündchen

Bleibt man noch gern am Feuer wach.

Man schürt, wann sich die Lohe senkt,

Die Funken auf und sinnt und denkt:

Nun abermal ein Tag!

Was Liebes oder Leides

Sein Lauf für uns daher gebracht,

Es geht noch einmal durch den Sinn,

Allein das Böse wirft man hin.

Es störe nicht die Nacht.

Zu einem frohen Traume

Bereitet man gemach sich zu.

Wann sorgelos ein holdes Bild

Mit sanfter Lust die Seele füllt,

Ergibt man sich der Ruh.

O wie ich mir gefalle

In meiner stillen Ländlichkeit!

Was in dem Schwarm der lauten Welt

Das irre Herz gefesselt hält,

Gibt nicht Zufriedenheit.

Zirpt immer, liebe Heimchen,

In meiner Klause, eng und klein.

Ich duld euch gern: ihr stört mich nicht.

Wann euer Lied das Schweigen bricht,

Bin ich nicht ganz allein.

When my crickets chirp

At night by my hearth, which stays warm late,

Then I sit in a cheerful mood,

I cosy up to the flames,

So light-spirited, so untroubled.

An intimate, quiet moment

Is still waiting for you as you stay up by the fire.

You poke it when the raging flames die down

So that the sparks appear, and you reflect and think:

Well that is another day done!

Everything that was enjoyable or painful,

Whatever the course of the day has brought,

It goes through your mind once more;

Only evil things need to be thrown away.

Don't let them disturb the night.

In anticipation of happy dreams

You slowly get ready.

When a carefree beautiful image

Fills your soul with gentle pleasure

You give yourself up to rest.

Oh, I so much like being

In my quiet rural surroundings.

In the buzz of the loud world whatever

Has imprisoned the crazy heart

Gives no satisfaction.

Keep on chirping, dear litttle cricket,

In my small, narrow cell.

I am happy to put up with you: you are not disturbing me.

When your song breaks the silence,

I am not totally alone.

Lappe, Der Einsame D 800

Hymnen an die Nacht / Hymns to night

Around the year 1800 there was a general shift in the mood and tone of German poems about night. The young Schubert had been attracted to many 18th century ghost stories and ‘gothick’ night scenes set in churchyards, but poets of the next generation (who came to be called ‘Romantics’) tended to see darkness as liberating rather than terrifying. Night-time offered an escape from the pressures of conventional day-time life and moonlight served as an image for the inner, spiritual enlightenment that might free us from the blinding delusions of outer society. Death appears to offer a fuller version of life, what Novalis called ‘a rejuvenating tide’:

Ich fühle des Todes

Verjüngende Flut,

Zu Balsam und Äther

Verwandelt mein Blut.

Ich lebe bei Tage

Voll Glauben und Mut

Und sterbe die Nächte

In heiliger Glut.

I can feel death's

Rejuvenating tide,

Into balsam and ether

My blood is being transformed.

By day I live

Full of faith and courage,

And during the nights I die

In a sacred glow.

von Hardenberg (Novalis), Nachthymne D 687

Novalis published his ‘Hymns to Night‘ (an ambitious mixture of poetic prose and mystical verse) in 1800. In 1802 Friedrich Schlegel published ‘Abendröte‘, a collection of 22 poems about ‘Sunset’ (1 – 11) and the world ‘After the Sun has Set’ (12 – 22). The second, night-time, section of this collection begins with ‘Der Wanderer‘, which Schubert set in 1819 (D 649). Here, the moonlight speaks ‘clearly’, progress is made in the darkness rather than in the daytime, and insight derives from ‘reflection’.

Wie deutlich des Mondes Licht

Zu mir spricht,

Mich beseelend zu der Reise:

"Folge treu dem alten Gleise,

Wähle keine Heimat nicht.

Ew'ge Plage

Bringen sonst die schweren Tage.

Fort zu andern

Sollst du wechseln, sollst du wandern,

Leicht entfliehend jeder Klage."

Sanfte Ebb' und hohe Flut

Tief im Mut,

Wandr' ich so im Dunkeln weiter;

Steige mutig, singe heiter,

Und die Welt erscheint mir gut.

Alles Reine

Seh ich mild im Wiederscheine,

Nichts verworren

In des Tages Glut verdorren:

Froh umgeben, doch alleine.

How clearly the moonlight

Is speaking to me,

Inspiring me on my journey:

"Follow the old track faithfully,

Do not choose any homeland.

Eternal torment

Would come along with the heavy days otherwise.

Onwards towards others

Is how you should change, is how you should travel,

Escaping lightly from every complaint."

Gentle ebb and high floods,

Deep in courage,

This is how I travel on in the darkness,

I climb courageously, I sing cheerfully,

And the world appears to me to be good.

All that is pure

I see gently in the reflection,

Nothing is confused

Or wilted in the embers of day:

Surrounded by happiness, yet alone.

F. Schlegel, Der Wanderer D 649

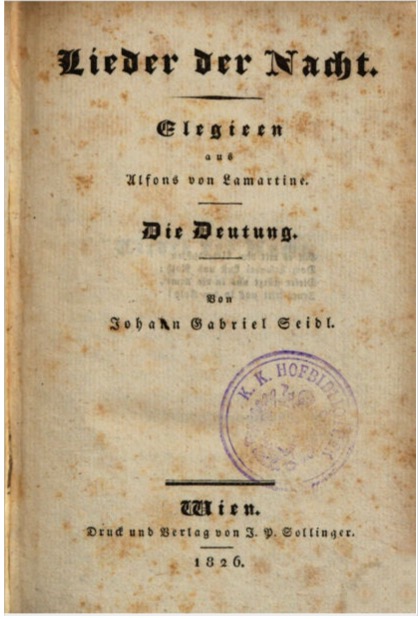

Towards the end of Schubert’s short life an even younger generation of poets attracted the composer’s attention. When Wilhelm August Rieder prepared a watercolour portrait of Schubert in 1825, he presented him holding a copy of the recently published ‘Lieder der Nacht‘ by Johann Gabriel Seidl (although the title page gives the publication date as 1826, as was common at this time it was available for sale a few months previously). Seidl was born as late as 1804. His collection of 55 poems (plus an introductory dedication) steps back from the intense mysticism of the Novalis Hymns to the Night, and from the introspective aestheticism of Schlegel’s ‘Sunset’ poems. For Seidl, night is gentle and reassuring. It might not be always be profound, but it remains the main locus of value. It is at night that we cherish friends and that is when moonlight reflects human affection and connection. Schubert went on to set seven of these poems in one of his many bursts of outstanding creativity towards the end of his life.

Seidl’s Der Wanderer an den Mond begins with the same scenario as Schlegel’s Der Wanderer (D 649). A lonely human traveller at night looks up at the moon and reflects on change and reflections. Schlegel’s arch-romantic poet notes that the lesson to be learnt from the moon is that we should never settle, we should tell ourselves that new experiences are new opportunities. Seidl’s traveller reads the situation differently. The moon’s course appears to him fixed. He (the moon) belongs in his sphere (and he will never come off the rails), whereas the human down in our confusing realm is never at home and can never reach his goal.

Ich auf der Erd, am Himmel du,

Wir wandern beide rüstig zu: -

Ich ernst und trüb, du mild und rein,

Was mag der Unterschied wohl sein?

Ich wandre fremd von Land zu Land,

So heimatlos, so unbekannt,

Bergauf, bergab, waldein, waldaus,

Doch bin ich nirgend, ach, zu Haus.

I am on the earth, you are in the sky,

We are both resolutely walking along:

I am serious and gloomy, you are gentle and pure,

What can explain the difference?

I walk on as a stranger from land to land,

So homeless, so unknown to others;

Up mountains and down mountains, into forests and out of forests,

Yet I am never - alas! - at home.

Seidl, Der Wanderer an den Mond D 870

In Am Fenster (D 878), Im Freien (D 880) and Nachthelle (D 892) the poet looks at the world illuminated by starlight and moonlight and thinks mainly of absent friends (many of whom we presume to be dead). The poetic persona appears to be desperate for some sort of inner illumination that will correspond with the light outside, and we somehow doubt the claims that everything is already resolved.

Ihr lieben Mauern, hold und traut,

Die ihr mich kühl umschließt

Und silberglänzend niederschaut,

Wenn droben Vollmond ist.

Ihr saht mich einst so traurig da,

Mein Haupt auf schlaffer Hand,

Als ich in mir allein mich sah,

Und keiner mich verstand.

Jetzt brach ein ander Licht heran:

Die Trauerzeit ist um:

Und manche ziehn mit mir die Bahn

Durch's Lebensheiligtum.

You beloved walls, beautiful and intimate,

Which enclose me in a cool way

And look down glowing with silver

When the full moon is up above:

You once saw me so sad here,

My head on my weary hand, -

When all I saw inside myself was me,

And nobody understood me.

Now a different light has appeared:

The time of mourning has passed:

And a number of others have joined me on the course

Through life's sanctuary.

Seidl, Am Fenster D 878

Die Nacht ist heiter und ist rein,

Im allerhellsten Glanz.

Die Häuser schaun verwundert drein,

Stehn übersilbert ganz.

In mir ist's hell so wunderbar,

So voll und übervoll,

Und waltet drinnen frei und klar,

Ganz ohne Leid und Groll.

Ich fass in meinem Herzenshaus

Nicht all das reiche Licht,

Es will hinaus, es muss hinaus,

Der letzte Schranke bricht.

The night is serene and is pure

In the brightest possible glow:

The houses are looking in with amazement,

They are completely covered in silver.

Inside me it is so wonderfully bright,

So full and overflowing,

And everything within is free and clear,

Totally without pain or resentment.

Within the house of my heart I cannot grasp

All of that rich light:

It wants to get out, it has to get out,

The last barrier has broken.

Seidl, Nachthelle D 892

The poet almost admits the emptiness of his claims to contentment and inner enlightenment in one of the bleakest texts in the Lieder der Nacht: Grab und Mond (Grave and moon).

Silberblauer Mondenschein

Fällt herab;

Senkt so manchen Strahl hinein

In das Grab.

Freund des Schlummers, lieber Mond,

Schweige nicht,

Ob im Grabe Dunkel wohnt,

Oder Licht!

Alles stumm? Nun stilles Grab,

Rede du,

Zogst so manchen Strahl hinab

In die Ruh;

Birgst gar manchen Mondenblick,

Silberblau,

Gib nur einen Strahl zurück: -

»Komm und schau.«

Silver-blue moonshine

Is streaming down;

So many rays of light are sinking

Into the grave.

Friend of sleep, dear moon,

Do not remain silent about

Whether it is darkness that dwells in the grave

Or light!

Not a sound? Now, silent grave,

You have to speak!

You pull down so many rays of light

To rest;

You hide so many of the moon's glances,

Silver-blue;

Just give one ray of light back: -

"Come and look!"

Seidl, Grab und Mond D893

☙

Descendant of:

Inanimate nature TIMETexts with this theme:

- Des Mädchens Klage, D 6, D 191, D 389 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Leichenfantasie, D 7 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Der Geistertanz, D 15, D 15A, D 116, D 494 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Die Schatten, D 50 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Der Taucher, D 77, D 111 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Zur Namensfeier des Herrn Andreas Siller, D 83 (Anonymous / Unknown writer)

- Erinnerungen, D 98, D 424 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Geisternähe, D 100 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Lied aus der Ferne, D 107 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Lied der Liebe, D 109 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- An Emma, D 113 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Romanze (Ein Fräulein klagt´ im finstern Turm), D 114 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- An Laura, als sie Klopstocks Auferstehungslied sang, D 115 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Nachtgesang (O! gib vom weichen Pfühle), D 119 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Trost in Tränen, D 120 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Mondabend, D 141 (Johann Gottfried Kumpf)

- Lodas Gespenst, D 150 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Die Erwartung, D 159 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- An Mignon, D 161 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Nähe des Geliebten, D 162 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Sängers Morgenlied, D 163, D 165 (Theodor Körner)

- Amphiaraos, D 166 (Theodor Körner)

- Nun lasst uns den Leib begraben (Begräbnislied), D 168 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Sehnsucht der Liebe, D 180 (Theodor Körner)

- An den Mond (Geuß, lieber Mond), D 193 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Die Mainacht, D 194 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- An die Nachtigall (Geuß nicht so laut), D 196 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Seufzer, D 198 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Die Nonne, D 208, D 212 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Die Laube, D 214 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Kolmas Klage, D 217 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Anonymous / Unknown writer)

- Der Abend (Der Abend blüht), D 221 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Lieb Minna, D 222 (Albert Stadler)

- Wandrers Nachtlied (Der du von dem Himmel bist), D 224 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Fischer, D 225 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Idens Nachtgesang, D 227 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Die Täuschung, D 230 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Das Sehnen, D 231 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Tischlied, D 234 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Abends unter der Linde, D 235, D 237 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Die Mondnacht, D 238 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Huldigung, D 240 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Das Geheimnis (Sie konnte mir kein Wörtchen sagen), D 250, D 793 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Der Gott und die Bajadere, D 254 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Schatzgräber, D 256 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- An den Mond (Füllest wieder Busch und Tal), D 259, D 296 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Morgenkuss, D 264 (Gabriele von Baumberg)

- Abendständchen. An Lina, D 265 (Gabriele von Baumberg)

- Das Leben ist ein Traum, D 269 (Johann Christoph Wannovius)

- An die Sonne (Sinke, liebe Sonne), D 270 (Gabriele von Baumberg)

- Abendlied (Groß und rotentflammet), D 276 (Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Cronnan, D 282 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Lied (Es ist so angenehm), D 284 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Furcht der Geliebten – An Cidli, D 285 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Selma und Selmar, D 286 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Die Sommernacht, D 289 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Die frühen Gräber, D 290 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Dem Unendlichen, D 291 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Shilric und Vinvela, D 293 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Mein Gruß an den Mai, D 305 (Johann Gottfried Kumpf)

- Die Sterne (Wie wohl ist mir im Dunkeln), D 313 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Nachtgesang (Tiefe Feier schauert um die Welt), D 314 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- An Rosa I, D 315 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Idens Schwanenlied, D 317 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Schwangesang, D 318 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Klage der Ceres, D 323 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Harfenspieler (Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt), D 325, D 478/1 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Lorma, D 327, D 376 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Erlkönig, D 328 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Entfernten, D 331, D 350 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Fischerlied, D 351, D 364, D 562 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Licht und Liebe (Nachtgesang), D 352 (Matthäus Karl von Collin)

- Die Nacht (Du verstörst uns nicht), D 358 (Johann Peter Uz)

- Zufriedenheit, D 362, D 501 (Matthias Claudius)

- Jägers Abendlied, D 215, D 368 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- An Schwager Kronos, D 369 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Lied (Mutter geht durch ihre Kammern), D 373 (Friedrich Heinrich de la Motte Fouqué)

- Abendlied (Sanft glänzt die Abendsonne), D 382 (Johann Christoph Heise)

- Laura am Klavier, D 388 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- An die Harmonie, D 394 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Die Herbstnacht, D 404 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Abschied von der Harfe, D 406 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Sprache der Liebe, D 410 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Klage (Die Sonne steigt, die Sonne sinkt), D 415 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Widerhall, D 428 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Erntelied, D 434 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Edone, D 445 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Aus Diego Manazares. Ilmerine (recte Aus Diego Manzanares. Almerine), D 458 (Ernestine von Krosigk)

- An Chloen (Bei der Liebe reinsten Flammen), D 462 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- In der Mitternacht, D 464 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- An den Mond (Was schauest du so hell), D 468 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Lied des Orpheus, als er in die Hölle ging, D 474 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen aß, D 478/2 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Sänger am Felsen, D 482 (Caroline Pichler)

- Lied (Ferne von der großen Stadt), D 483 (Caroline Pichler)

- Abendlied (Der Mond ist aufgegangen), D 499 (Matthias Claudius)

- Lebenslied, D 508, D Anh. I, 23 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Jagdlied, D 521 (Friedrich Ludwig Zacharias Werner)

- Täglich zu singen, D 533 (Matthias Claudius)

- Die Nacht, D 534 (James Macpherson (Ossian) and Edmund von Harold)

- Memnon, D 541 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Uraniens Flucht, D 554 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Vollendung, D 579A (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- An den Mond in einer Herbstnacht, D 614 (Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber)

- Blondel zu Marien, D 626 (Josephine von Münk-Holzmeister)

- Sonett (Nunmehr, da Himmel, Erde schweigt), D 630 (Francesco Petrarca and Johann Diederich Gries)

- Abend, D 645 (Johann Ludwig Tieck)

- Der Wanderer (Wie deutlich des Mondes Licht), D 649 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Abendbilder, D 650 (Johann Peter Silbert)

- Bertas Lied in der Nacht, D 653 (Franz Grillparzer)

- Beim Winde, D 669 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die Sternennächte, D 670 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Trost (Hörnerklänge rufen klagend), D671 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Nachtstück, D 672 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Morgenlied (Eh die Sonne früh aufersteht), D 685 (Friedrich Ludwig Zacharias Werner)

- Nachthymne, D 687 (Friedrich Leopold von Hardenberg (Novalis))

- Der Schiffer (Friedlich lieg ich hingegossen), D 694 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Des Fräuleins Liebeslauschen, D 698 (Franz von Schlechta)

- Freiwilliges Versinken, D 700 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Der Jüngling auf dem Hügel, D 702 (Heinrich Hüttenbrenner)

- Im Walde (Waldesnacht), D 708 (Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel)

- Der Unglückliche / Die Nacht, D 713, D deest (Caroline Pichler)

- Die Nachtigall (Bescheiden verborgen), D 724 (Johann Carl Unger)

- Mignon (Heiß mich nicht reden), D 726, D 877/2 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Der Blumen Schmerz, D 731 (Johann (János) Nepomuk Josef Graf Mailáth)

- Nachtviolen, D 752 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Du liebst mich nicht, D 756 (August von Platen Hallermünde)

- Schwestergruß, D 762 (Franz von Bruchmann)

- Willkommen und Abschied, D 767 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Wanderers Nachtlied (Über allen Gipfeln), D 768 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Drang in die Ferne, D 770 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Die Mutter Erde, D 788 (Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Vergissmeinnicht, D 792 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Morgengruß, D 795/8 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Tränenregen, D 795/10 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Der Müller und der Bach, D 795/19 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Des Baches Wiegenlied, D 795/20 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Romanze (Ariette): Der Vollmond strahlt, D 797/3b (Wilhelmine Christiane von Chézy)

- Geisterchor, D 797/4 (Wilhelmine Christiane von Chézy)

- Der Einsame, D 800 (Karl Lappe)

- Gondelfahrer, D 808, D 809 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Nacht und Träume, D 827 (Matthäus Karl von Collin)

- Die junge Nonne, D 828 (Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Abschied (Leb wohl, du schöne Erde), D 829 (Adolph Pratobevera von Wiesborn)

- Der blinde Knabe, D 833 (Colley Cibber and Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Totengräbers Heimwehe, D 842 (Jacob Nicolaus Craigher de Jachelutta)

- Normans Gesang, D 846 (Walter Scott and Philip Adam Storck)

- Nachtmusik, D 848 (Siegmund von Seckendorff)

- Auf der Bruck, D 853 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Abendlied für die Entfernte, D 856 (August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Zwei Szenen aus dem Schauspiel “Lacrimas”, Lied des Florio, D 857/2 (Christian Wilhelm von Schütz)

- Um Mitternacht, D 862 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Der Wanderer an den Mond, D 870 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Das Zügenglöcklein, D 871 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Mondenschein, D 875 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Am Fenster, D 878 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Im Freien, D 880 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Nachthelle, D 892 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Grab und Mond, D 893 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Fröliches Scheiden, D 896 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Sie in jedem Liede, D 896A (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Zur guten Nacht, D 903 (Friedrich Rochlitz)

- Alinde, D 904 (Friedrich Rochlitz)

- An die Laute, D 905 (Friedrich Rochlitz)

- Romanze des Richard Löwenherz, D 907 (Walter Scott and Karl Ludwig Methusalem Müller)

- Jägers Liebeslied, D 909 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Gute Nacht, D 911/1 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Der Lindenbaum, D 911/5 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Täuschung, D 911/19 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Nachtgesang im Walde, D 913 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Ständchen (Zögernd leise), D 920 (Franz Grillparzer)

- Das Weinen, D 926 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Des Fischers Liebesglück, D 933 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Der Winterabend, D 938 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Die Sterne (Wie blitzen), D 939 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Ständchen, D 957/4 (Ludwig Rellstab)

- Der Doppelgänger, D 957/13 (Heinrich Heine)

- Der Hirt auf dem Felsen, D 965 (Wilhelm Müller and Karl August Varnhagen von Ense)

- Jünglingswonne, D 983 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Zum Rundetanz, D 983B, D Anh. I, 18 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Die Nacht, D 983C (Friedrich Adolph Krummacher)

- Gott im Ungewitter, D 985 (Johann Peter Uz)