Die Wallfahrt

Meine Tränen im Bußgewand

Die Wallfahrt haben

Zur Kaaba der Schönheit angetreten;

In der Wüste brennendem Sand

Sind sie begraben,

Nicht hingelangten sie anzubeten.

The pilgrimage

In penitential clothing my tears

Set off on a pilgrimage

To the Kaaba of beauty.

In the burning sand of the desert

They have been buried,

They did not allow me to worship.

Friedrich Rückert (D 778A)

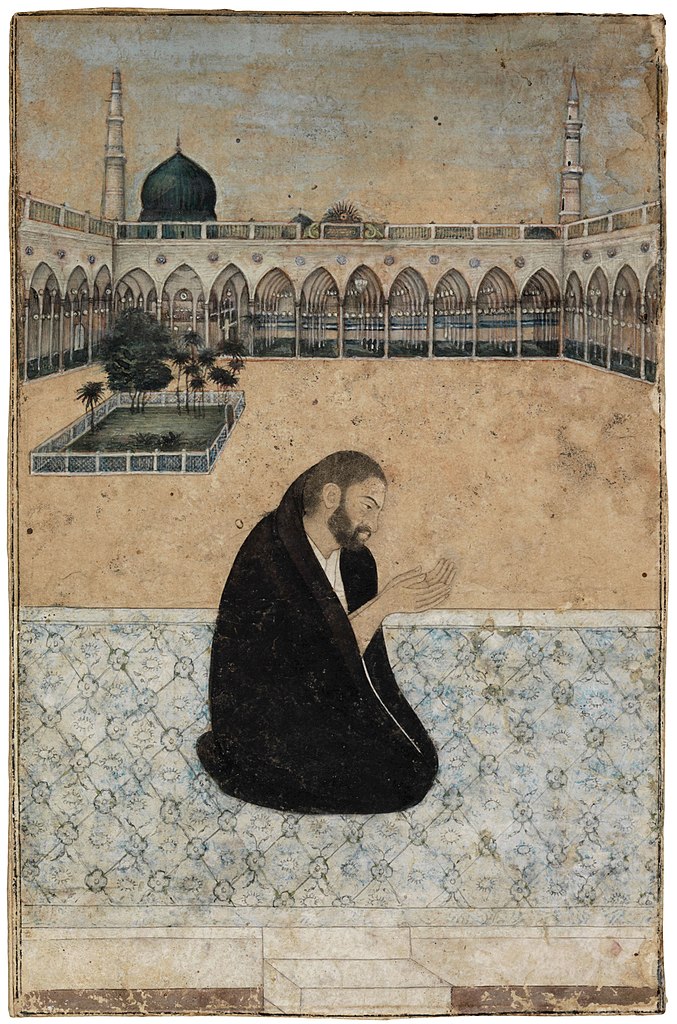

Although the Hajj to the Kaaba in Mecca is one of the ‘Five Pillars of Islam’, many Muslim traditions have accepted that an inner spiritual progress is more significant than the actual physical journey. Rückert’s verse, based as it is on a profound knowledge and understanding of Persian poetry, draws attention to this symbolic use of the image of being a pilgrim.

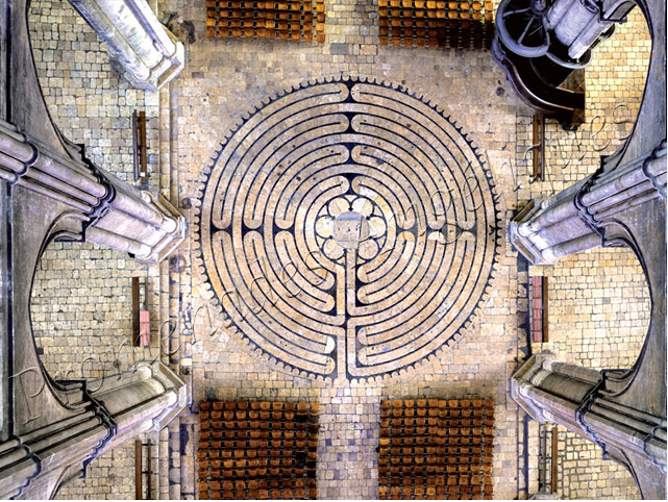

All of the monotheistic religions have treated pilgrimage as both an outer and an inner phenomenon. In the days of the Temple in Jerusalem, the priestly tradition insisted on regular attendance and sacrifice, whereas many in the prophetic tradition felt that this encouraged corruption, or at least distracted from true piety (“Rend your heart and not your garments, and turn unto the LORD your God”, Joel 2:13). In the heyday of pilgrimage in Western Europe, as crusading armies ‘processed’ to Jerusalem, a more symbolic ‘journey to Jerusalem’ was built into the pavement of the nave of Chartres Cathedral.

It appears that pilgrims took this winding route on their knees, traversing a simplified image of time and space (there are twelve circles representing 12 months and 4 sectors representing the 4 seasons and the 4 cardinal points). Attaining the goal, ‘the still point of the turning world / wheel’ at the centre of the labyrinth, was never in doubt. The significance lay in the journey towards it (which initially seems to be direct though it involves many later diversions and seeming reverses).

In Leitner’s ‘Der Kreuzzug’ (The Crusade), Schubert’s D 932, a monk reflects on his inability to travel as he watches soldiers embark for the Holy Land (hoping to ‘liberate’ the Holy Sepulchre). Then he realises that he too has the opportunity to go on a ‘journey to Jerusalem’. Like the pilgrims at Chartres, he can be part of a symbolic procession towards the centre of all things. Even without leaving his cell, he can offer prayers that will enable him to ‘travel’.

Around the time when the Chartres labyrinth (the ‘path to Jerusalem’) was being designed (the early 13th century), one of the most popular themes in western European literature was ‘the quest for the Holy Grail’. In texts such as the ‘Queste del Saint Graal’ (part of the ‘Prose Lancelot’) the focus is clearly on the process of the quest itself rather than the object. Indeed the narrative begins with the Holy Grail descending to King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. They are all given their favourite food, but as the Grail departs, Sir Gawain and others declare that is is now necessary to set off on ‘a quest for the Holy Grail’! As in the pattern of the labyrinth, we begin by approaching the goal, only to be diverted from it. The quest is going to be long and tortuous, but therein lies its value.

Schiller’s ‘Der Pilgrim’ (D 794) gives voice to someone trapped on just such a tortuous quest. The speaker has now realised that the goal is ever distant, that the object being striven for may be unattainable, that ‘there’ will never be ‘here’.

Hin zu einem großen Meere

Trieb mich seiner Wellen Spiel,

Vor mir liegt's in weiter Leere,

Näher bin ich nicht dem Ziel.

Ach kein Weg will dahin führen,

Ach der Himmel über mir

Will die Erde nicht berühren,

Und das Dort ist niemals Hier.

I was taken off to a great ocean,

The play of its waves carried me along,

Lying in front of me is a broad expanse,

I am no nearer to my goal.

Oh, no path is going to lead there,

Oh the sky above me

Is not going to touch the earth,

And 'there' is never 'here'.

☙

Descendant of:

THE COURSE OF HUMAN LIFE: From the cradle to the grave MOVEMENT RELIGIONTexts with this theme:

- Elysium, D 51, D 53, D 54, D 57, D 58, D 60, D 584 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Naturgenuss, D 188, D 422 (Friedrich von Matthisson)

- Der Liedler, D 209 (Joseph Kenner)

- Adelwold und Emma, D 211 (Friedrich Anton Franz Bertrand)

- Die Laube, D 214 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Ritter Toggenburg, 397 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Der Leidende, D 432 (Anonymous / Unknown writer)

- Die Perle, D 466 (Johann Georg Jacobi)

- Abschied, nach einer Wallfahrstarie bearbeitet, D 475 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Das Marienbild, D 623 (Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber)

- Ihr Grab, D 736 (Karl August Engelhardt)

- Heliopolis I, D 753 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Die Wallfahrt, D 778A (Friedrich Rückert)

- Pilgerweise, D 789 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Der Pilgrim, D 794 (Friedrich von Schiller)

- Der Wanderer an den Mond, D 870 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Das Zügenglöcklein, D 871 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Der Kreuzzug, D 932 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)

- Die Sterne (Wie blitzen), D 939 (Carl Gottfried von Leitner)