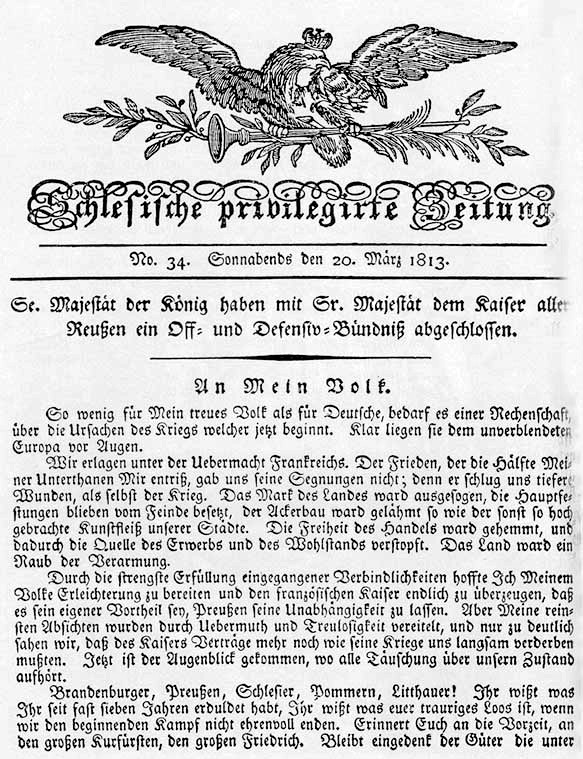

On 17th March 1813 King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia issued a proclamation justifying his participation in the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon. He appealed to his people (“Brandenburgers, Prussians, Silesians, Pomeranians, Lithuanians!”) to put behind them the previous seven years of collaboration with the French now that it was apparent that ‘peace’ had inflicted more wounds than war. By the following spring the King of Prussia (alongside the Emperors of Russia and Austria) had entered Paris and Napoleon had been exiled to Elba.

It was at this point that Mikan wrote a celebratory poem that hailed Friedrich Wilhelm as the person that had ‘awoken the bold Prussians again’ (Der Wiedererwecker der tapferen Preußen):

Sie sind in Paris!

Die Helden! Europas Befreier!

Der Vater von Öst'reich, der Herrscher der Reußen,

Der Wiedererwecker der tapferen Preußen!

Das Glück Ihrer Völker, es war ihnen teuer,

Sie sind in Paris!

Nun ist uns der Friede gewiss!

They are in Paris!

The heroes! Europe's liberators!

The father of Austria, the lord of the Russians,

He who woke up the bold Prussians.

The happiness of their people - it came at a price.

They are in Paris!

Now peace is guaranteed for us!

Mikan, Die Befreier Europas in Paris D 104

One of the people that fought (and died) for the Prussians during this ‘War of Liberation’ was Theodor Körner, whose Sängers Morgenlied gloried in the thrill of waking up to a new day:

Süßes Licht! Aus goldenen Pforten

Brichst du steigend durch die Nacht,

Schöner Tag, du bist erwacht.

Mit geheimnisvollen Worten,

In melodischen Akkorden,

Grüß ich deine Rosenpracht.

Sweet light! Out of golden doors

You break as you climb through the night.

Beautiful day! You have woken up.

With mysterious words,

In melodious chords,

I greet your rosy majesty!

Körner, Sängers Morgenlied D 163, D 165

Although these lines were written in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, by the time Schubert came to set them the Congress of Vienna was already in session and it appeared that the new day had dawned. Körner was now commemorated as one of the patriots who had been awoken by the King of Prussia.

So pervasive has the image become that we might not even realise that the language is metaphorical. Coming to accept that a situation is no longer tolerable or realising that we may have misunderstood or misinterpreted things is called an ‘awakening’. Immanuel Kant used the image when he wrote about how the work of David Hume awoke him from his ‘dogmatic slumber’. Throughout 18th and 19th century North America the evangelical movements came to be called ‘the Great Awakening’.

The same metaphor underlies the more modern usage of the word ‘woke’ (though it is unlikely that many of the people who use this term would apply it to the decision of a Prussian king to go to war against his former ally!). It is perhaps inevitable that people who change their opinions or values look back on their previous position as a sort of ‘sleep’ from which they have been awoken.

This basic metaphor even lurks behind more literal references to ‘waking up’. When Cloten, the oafish wooer in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline, arranges for a song to be performed to awaken Imogen, he is not just telling her to get out of bed – the aim is for her to change her attitude to him:

Horch, horch, die Lerch im Ätherblau,

Und Phöbus, neu erweckt,

Tränkt seine Rosse mit dem Tau,

Der Blumenkelche deckt;

Der Ringelblume Knospe schleußt

Die goldnen Äuglein auf;

Mit allem, was da reizend ist,

Du süße Maid, steh auf,

Steh auf, steh auf.

Hark, hark, the lark at heaven's gate sings,

And Phoebus 'gins arise,

His steeds to water at those springs

On chaliced flowers that lies,

And winking Mary-buds begin to ope their golden eyes.

With every thing that pretty is, my lady sweet, arise,

Arise, arise.

Shakespeare / Voß, Ständchen (Horch, horch, die Lerch) D 889

Cloten failed in his attempt to seduce Imogen, but we can see what he wanted to achieve in Klopstock’s Das Rosenband, where the speaker is waiting for a girl in a spring-time garden to wake up. When their eyes meet, the girl has not just awoken from sleep, she has awoken to a new life of love:

Im Frühlingsgarten fand ich sie,

Da band ich sie mit Rosenbändern,

Sie fühlt' es nicht und schlummerte.

Ich sah sie an, mein Leben hing

Mit diesem Blick an ihrem Leben,

Ich fühlt' es wohl und wusst' es nicht.

Doch lispelt' ich ihr leise zu,

Und rauschte mit den Rosenbändern,

Da wachte sie vom Schlummer auf,

Sie sah mich an, ihr Leben hing

Mit diesem Blick an meinem Leben,

Und um uns ward Elysium.

I found her in the spring garden,

There I tied her with rose ribbons:

She did not feel it and carried on sleeping.

I looked at her; my life was hanging

On her life with that glance:

I felt it clearly and I did not know it.

But I whispered to her gently

And made a noise with the pink ribbons.

At that she woke up from her nap.

She looked at me; her life was hanging

On my life with that glance:

And around us everything turned into Elysium.

Klopstock, Das Rosenband D 280

There is a tension here between the reality that floods into consciousness on waking and the susceptibility to new sensation offered by sleep. It seems as if the girl needs the numbness of sleep to help her become aware of her emotion, just as she needs the bond of the tied ribbon to liberate her. Another poem that tries to capture this paradox of slumber as a precondition for wakefulness is Der Jüngling an der Quelle by Salis-Seewis. Here, love wakes up because of rustling sounds that induce sleep. The speaker and the beloved awaken to a lullaby:

Leise rieselnder Quell! ihr wallenden, flispernden Pappeln;

Euer Schlummergeräusch wecket die Liebe nur auf.

Linderung sucht' ich bei euch, und sie zu vergessen, die Spröde,

Ach und Blätter und Bach seufzen, Luise! dir nach.

Gentle, trickling spring! You swaying, whispering poplars;

Your sleepy sounds only serve to awaken love.

I came to you looking for comfort and to forget her - the one who is hard to get.

Alas, both the leaves and the brook are sighing for you, Luise!

Salis-Seewis, Der Jüngling an der Quelle D 300

In other texts, dreams are seen as delusions rather than revelations, and waking up is a matter of coming to terms with their unreality. In Frühlingstraum (Winterreise), the speaker is shocked at the difference between sleeping and waking:

Ich träumte von bunten Blumen,

So wie sie wohl blühen im Mai,

Ich träumte von grünen Wiesen,

Von lustigem Vogelgeschrei.

Und als die Hähne krähten,

Da ward mein Auge wach,

Da war es kalt und finster,

Es schrieen die Raben vom Dach.

I dreamt of colourful flowers,

About the way they blossom in May,

I dreamt of green meadows,

About birds singing happily.

And when the cocks crew

My eye was then alert;

Then it was cold and dark,

The ravens on the roof were shrieking.

Müller, Frühlingstraum D 911 11

The speaker in Schulze’s Lebensmut (Courage for life) takes the difference between dream and reality, between sleeping and being awake, as a spur to more positive activity:

Dieses Zagen, dieses Sehnen,

Das die Brust vergeblich schwellt,

Diese Seufzer, diese Tränen,

Die der Stolz gefangen hält,

Dieses schmerzlich eitle Ringen,

Dieses Kämpfen ohne Kraft,

Ohne Hoffnung und Vollbringen,

Hat mein bestes Mark erschlafft.

Lieber wecke rasch und mutig,

Schlachtruf, den entschlafnen Sinn!

Lange träumt' ich, lange ruht' ich,

Gab der Kette lang mich hin.

Hier ist Hölle nicht, noch Himmel,

Weder Frost ist hier, noch Glut,

Auf ins feindliche Getümmel,

Rüstig weiter durch die Flut.

Dass noch einmal Wunsch und Wagen,

Zorn und Liebe, Wohl und Weh

Ihre Wellen um mich schlagen

Auf des Lebens wilder See,

Und ich kühn im tapfern Streite

Mit dem Strom, der mich entrafft,

Selber meinen Nachen leite,

Freudig in geprüfter Kraft.

This hesitation, this longing,

Which has been pointlessly swelling my breast,

These sighs, these tears,

Which are held captive by pride,

This painful useless wrestling,

This battling without power,

Without hope or achievement,

Has drained the marrow of my being.

Better to wake up, swift and courageous,

With a battle cry rousing my sleeping mind!

I have been dreaming for a long time, I have been resting for a long time,

For a long time I allowed myself to be chained up;

Here is neither hell nor heaven,

There is neither frost nor flame here!

Up into the enemy turmoil,

Confidently pressing on through the flood!

Let them come again - desire and daring,

Rage and love, ecstasy and misery -

Let their waves beat around me

On the savage sea of life;

And I shall be bold in the courageous struggle

With the stream that is engulfing me,

I shall guide my boat myself

Joyfully using my well-tested strength.

Schulze, Lebensmut D 883

☙

Descendant of:

TIME REALITY AND UNREALITYTexts with this theme:

- Die Befreier Europas in Paris, D 104 (Johann Christian Mikan)

- Sängers Morgenlied, D 163, D 165 (Theodor Körner)

- Der Liebende, D 207 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty and Johann Heinrich Voß)

- Der Traum, D 213 (Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty)

- Der Gott und die Bajadere, D 254 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- Morgenlied, D 266 (Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg)

- Das Leben ist ein Traum, D 269 (Johann Christoph Wannovius)

- An die Sonne (Königliche Morgensonne), D 272 (Christoph August Tiedge)

- Das Rosenband, D 280 (Friedrich Gottlob Klopstock)

- Der Jüngling an der Quelle, D 300 (Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis)

- Die Sterne (Wie wohl ist mir im Dunkeln), D 313 (Ludwig Theobul Kosegarten)

- Der Sänger am Felsen, D 482 (Caroline Pichler)

- Lied (Ferne von der großen Stadt), D 483 (Caroline Pichler)

- Bei dem Grabe meines Vaters, D 496 (Matthias Claudius)

- Beim Winde, D 669 (Johann Baptist Mayrhofer)

- Frühlingsglaube, D 686 (Johann Ludwig Uhland)

- Lachen und Weinen, D 777 (Friedrich Rückert)

- Viola, D 786 (Franz Adolph Friedrich von Schober)

- Morgengruß, D 795/8 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Ellens Gesang II (Jäger, ruhe von der Jagd), D 838 (Walter Scott and Philip Adam Storck)

- Wiegenlied, D 867 (Johann Gabriel Seidl)

- Lebensmut, D 883 (Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze)

- Ständchen (Horch, horch, die Lerch), D 889 (William Shakespeare, Abraham Sophus Voß, and August Wilhelm Schlegel)

- Wein und Liebe, D 901 (Friedrich Haug)

- Frühlingstraum, D 911/11 (Wilhelm Müller)

- Frühlingslied, D 914, D 919 (Aaron Pollack)