On the lake

(Poet's title: Auf dem See)

Set by Schubert:

D 543

[March 1817]

Und frische Nahrung, neues Blut

Saug ich aus freier Welt;

Wie ist Natur so hold und gut,

Die mich am Busen hält!

Die Welle wieget unsern Kahn

Im Rudertakt hinauf,

Und Berge, wolkig himmelan,

Begegnen unserm Lauf.

Aug, mein Aug, was sinkst du nieder?

Goldne Träume, kommt ihr wieder?

Weg, du Traum, so Gold du bist,

Hier auch Lieb und Leben ist.

Auf der Welle blinken

Tausend schwebende Sterne,

Weiche Nebel trinken

Rings die türmende Ferne;

Morgenwind umflügelt

Die beschattete Bucht,

Und im See bespiegelt

Sich die reifende Frucht.

And fresh nutrition, new blood,

I suck from this open world;

Nature is so beautiful and good,

Holding me to its breast!

The waves are rocking our boat

With the rhythm of the oars,

And mountains, in clouds reaching up to the sky,

Come to meet us as we make our way.

Eye, my eye, why are you sinking down?

Golden dreams, are you going to return?

Begone, dream! however golden you are;

Here too there is love and life.

Twinkling on the waves

Are a thousand hovering stars,

Gentle mists are drinking

Up the looming distance;

The morning wind is flying around

The shaded bay,

And mirrored in the lake

Is the ripening fruit.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Blood Boats and ships Chest / breast Clouds Dreams Eyes Flying, soaring and gliding Food, feeding and nursing Fruit Gold Heaven, the sky Here and there Hills and mountains Lakes Mirrors and reflections Mist and fog Morning and morning songs Mountains and cliffs Near and far On the water – rowing and sailing Rocking Stars Surface of the water Swaying and swinging Waves – Welle Wind

‘On the Lake’. One picnic, two Schubert songs and three poems

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Au_Halbinsel_-_ZSG_Helvetia_2015-09-09_17-33-42.JPG

"We got into a boat and set off on a dazzling morning out onto the magnificent lake. Permit me to convey a sense of those happy moments by interpolating a poem: And fresh nutrition, new blood, I suck from this open world; Nature is so beautiful and good, Holding me to its breast! The waves are rocking our boat With the rhythm of the oars, And mountains, in clouds reaching up to the sky, Come to meet us as we make our way. Eye, my eye, why are you sinking down? Golden dreams, are you going to return? Begone, dream! however golden you are; Here too there is love and life. Twinkling on the waves Are a thousand hovering stars, Gentle mists are drinking Up the looming distance; The morning wind is flying around The shaded bay, And mirrored in the lake Is the ripening fruit. We landed at Richterswil, where Lavater had arranged for us to meet Doctor Hotze."

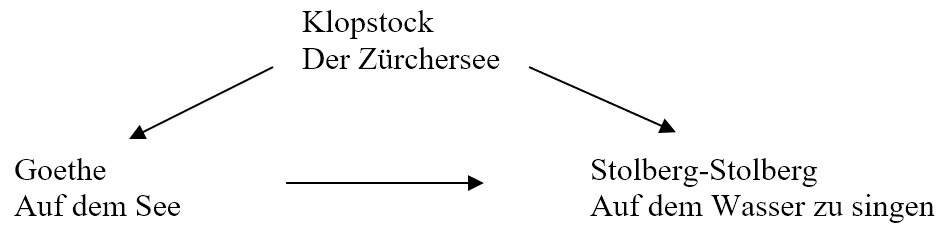

These details about the first day of an excursion from Zürich that would take the visitors from the north as far south as the Gotthard Pass are from Goethe’s autobiography, ‘Dichtung und Wahrheit‘ (Poetry and Truth). They refer to an incident on 15th June 1775. After his arrival in Zürich with his friends the Stolberg brothers, Goethe had been greeted by Lavater (the physiognomist) and their young friend Jakob Ludwig Passavant, who suggested a trip into the Alps. The resulting expedition began as a homage to Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, who held a semi-mythical status for some of this group. In Goethe’s recent novel, The Sufferings of Young Werther, Lotte only needs to say the one word ‘Klopstock’ while looking out at a thunderstorm for Werther to recall the relevant Ode and recognise the depth of her sensitivity. One of Goethe’s new anonymous female correspondents (playing the role of Charlotte to his Werther) turned out to be the sister of Friedrich Leopold and Christian zu Stolberg-Stolberg, members of the Göttinger Hainbund, an association of devotees of Klopstock.

Goethe had arrived in Zürich in the company of the Stolberg brothers, who were presumably responsible for the idea of celebrating the 25th anniversary of Klopstock’s Ode, Der Zürchersee (Lake Zurich). This 19 stanza poem, written in 1750, recounts the experience of a group of friends both on the water and during a picnic (with singing) on the Au (‘meadow’) Peninsula on the south bank of Lake Zurich. Klopstock writes of the beauty of the lake and the even greater beauty of the responsive souls of the people on it as they remember the grape-clad hillsides that they have passed and look up at the silvery Alpine peaks in the distance.

Schön ist, Mutter Natur, deiner Erfindung Pracht

Auf die Fluren verstreut, schöner ein froh Gesicht,

Das den großen Gedanken

Deiner Schöpfung noch Einmal denkt.

Von des schimmernden Sees Traubengestaden her,

Oder, flohest du schon wieder zum Himmel auf,

Komm in röthendem Strale

Auf dem Flügel der Abendluft,

Komm, und lehre mein Lied jugendlich heiter seyn,

Süße Freude, wie du! gleich dem beseelteren

Schnellen Jauchzen des Jünglings,

Sanft, der fühlenden Fanny gleich.

The splendour of your inventiveness is beautiful, Mother Nature,

Spread out over the fields, and even more beautiful is a happy face

That is paying attention to the great thoughts

Of your creation once again.

Come back from the grape-lined banks of the shimmering lake,

Or, if you have already flown off back to the heavens,

Come back in reddening beams,

On the wings of evening air,

Come and teach my song to be youthfully cheerful,

Sweet Joy, like you! like the inspired

Prompt cheering of this lad,

Soft, with feeling, like Fanny.

As Klopstock and his friends sang Albrecht von Haller’s Ode ‘To Doris’ in the shade of the woods of the Au peninsula (Klopstock calls it Au Island) the Joy that had been invoked overwhelmed them.

Most of Klopstock’s Ode deals with specific times and places, and explicitly named individuals. An exception to this, though, is one of the addressees of the Ode, Fanny. In reality, the Fanny whose sensitivity is praised in Stanza 3 and whose absence and unavailability establish the tone for the end of the poem, was Klopstock’s cousin Maria Sophia Schmidt. Der Zürchersee ends with Klopstock (or the poetic persona) asserting that if only Fanny were present, this location in the valley of Lake Zürich, with its shady woods, would turn into Elysium itself and we could live here in ‘huts of friendship’ for ever more.

Treuer Zärtlichkeit voll, in den Umschattungen,

In den Lüften des Walds, und mit gesenktem Blick

Auf die silberne Welle,

That ich schweigend den frommen Wunsch:

Wäret ihr auch bey uns, die ihr mich ferne liebt,

In des Vaterlands Schooß einsam von mir verstreut,

Die in seligen Stunden

Meine suchende Seele fand;

O so bauten wir hier Hütten der Freundschaft uns!

Ewig wohnten wir hier, ewig! Der Schattenwald

Wandelt’ uns sich in Tempe,

Jenes Thal in Elysium!

Full of true tenderness, surrounded by the shadows

And breezes of the wood, and looking down

To the silver waves,I made a pious silent wish:

If you were with us too, you who love me from afar,

Separated from me in the bosom of the fatherland,

You who in a happy hour

Found my searching soul,

Oh then we would build ourselves huts of friendship!

We would live here for ever! Eternally! The shady wood

Would turn into Tempe for us

And this valley would be Elysium!

Der Zürchersee is therefore both a celebration of the here and now and at the same time a recognition that our responses to nature and friendship are not always immediate and complete. It may be this tension that intrigued Goethe in June 1775 as he participated in a recreation of the experience of Klopstock and his friends. He had recently become engaged and the famous unsettled and unsettling author of Werther was about to ‘settle down’. Yes, he wanted to be grounded. He was horrified by the irrational manic reception of his novel, and he needed to pay more attention to the empirical. He wanted to draw. He wanted to be a natural philosopher. Yet he also knew that he had to pursue his projects, that he could never be satisfied with where he was now, that there was a world to discover and understand beyond his reach. Here he was on a journey to that borderland of the northern imagination, to the mountain peaks beyond which lay Italy itself. Should he transcend or would this be a transgression?

The boat party he was part of must have read (or even sung) Klopstock’s Ode, and Goethe’s response, the lyric ‘Auf dem See’, seems to begin as a direct response to Klopstock. ‘Und frische Nahrung, neues Blut, / Saug ich aus freier Welt’ is surely a response to Klopstock’s opening image: Mother Nature. Goethe takes the image at its word. If nature is a mother she nurtures, with blood (in the womb) and milk (at the breast). This ‘fresh’ nutrition, this ‘new’ blood, is a typically Goethean reaction to his predecessors, who are only understood and honoured in recreation and our own creativity, not in pious repetition and veneration. He is determined to draw not just on Klopstock himself but on the creative juices which fed both of them, at different times but at the same place, Zürich, the home of ‘free citizens’ (Klopstock stanza 4, echoed in Goethe’s phrase ‘aus freier Welt’). The whole of the first stanza of Goethe’s lyric can be read as a reaction to Klopstock’s text. Nature holding me to her bosom does not just pick up on the ‘mother’ imagery (which Klopstock had not developed). Nature is a lover too. In Stanza 16 of the Ode Klopstock had declared that the sweetest and most beautiful of all experiences open to the sensitive soul was ‘in the arms of a friend, knowing yourself to be a friend’.

In the course of ‘Auf dem See‘ Goethe moves from animal imagery (suckling and moving) to the language of plants. The ripening fruit at the end of the text recall the grape-lined banks noted by Klopstock, but their function in the text is something new (they refer to the promise of the works of a newly rooted Goethe coming to fruition). Even more original is what Goethe makes of Klopstock looking down onto the waves of the lake from within the shadow of the woods (stanzas 17 – 19). Goethe looks down and looks into a mirror. Looking down at the water allows him to see up to the stars. Accepting where he is allows him to see beyond the mountains. There is no secret longing to be with a distant beloved. There is nothing stopping here and now being Elysium. We need to imagine Goethe landing at the Au peninsula on the morning of 15th June 1775, having heard the Stolberg brothers read out Klopstock’s Ode a couple of times whilst on the water. Instead of reciting it himself, he rewrites it as a much more succinct lyric. In response to the end of Klopstock’s text (looking down at the waves etc) Goethe says he has something to add. The opening ‘and’ shows that the text is a continuation or a response of some kind. There seems to be little doubt that it can be read as an addendum to Klopstock’s ‘Lake Zürich‘.

Schubert was to set ‘Auf dem See’ in March 1817 (D 543), and about six years later he set ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen‘ (D 774), a barcarolle by Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg.

Auf dem Wasser zu singen

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet, wie Schwäne, der wankende Kahn;

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendrot rund um den Kahn.

Über den Wipfeln des westlichen Haines

Winket uns freundlich der röthliche Schein;

Unter den Zweigen des östlichen Haines

Säuselt der Kalmus im röthlichen Schein;

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Athmet die Seel’ im erröthenden Schein.

Ach, es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit;

Morgen entschwindet mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem strahlendem Flügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

To be sung on the water

In the middle of the shimmer of the mirroring waves

The rocking boat is gliding like swans;

Oh, on the gently shimmering waves of joy

The soul is gliding along like the boat;

Because coming down from the sky onto the waves

The sunset is dancing around the boat.

Over the treetops of the woods in the west

The reddish glow is beckoning to us in a friendly way;

Under the branches of the woods in the east

The acorus plants are rustling in the reddish glow;

The joy of heaven and the calm of the woods

– The soul is breathing these in in the reddening glow.

Oh, with its dewy wings it is vanishing,

Time is vanishing for me on these rocking waves;

With shimmering wings it is going to vanish tomorrow

Again, time will vanish like yesterday and today,

Until I, on higher, beaming wings,

Myself vanish into changing time.

Schubert probably did not know that Stolberg had been with Goethe on the banks of Lake Zürich on the day when he wrote ‘Auf dem See‘. By the time Schubert set ‘Auf dem See‘ Goethe and Stolberg had drifted apart (and Stolberg died in 1819). There therefore seems little to connect these two famous songs apart from the watery theme and Schubert’s similar response to it. As Graham Johnson writes in his comments on ‘Auf dem See‘ (Hyperion Schubert Edition, Volume 19, track 16), “The songs were written some six years apart and yet the response to the image of cradling water is somewhat similar.”

However, I would like to suggest a deeper connection. ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen‘ could be read as Stolberg’s own response to Klopstock’s Ode and it appears to acknowledge Goethe’s earlier response. The text was written in 1782, so at least 6 years after the picnic at Au on the banks of Lake Zürich and Goethe’s ‘Auf dem See’. It is clearly a nocturne rather than an aubade (in Goethe’s ‘Auf dem See‘ it is the stars of early morning that are seen in the lake), reflecting on the water as the sun sets and our thoughts turn to the passing of time and death itself. Nevertheless, the optimistic tone and the hypnotic simplicity of the repeated limited rhymes make Stolberg’s poem the sort of cheerful song Klopstock had himself wanted his Ode to be (stanza 3). The text does not explicitly state that the water is a lake, but the reference to woods on the east and the west side is consistent with the view looking towards Zürich from Au.

If Goethe was ‘quoting’ Klopstock’s first stanza and its invocation of ‘Mother Nature’ at the beginning of ‘Auf dem See‘, Stolberg is perhaps evoking memories of the second stanza. He is recalling looking at the surface of the lake, but as a practising poet what he sees is refracted by other texts.

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen / Gleitet, wie Schwäne, der wankende Kahn.

We catch a glimpse here of Klopstock’s ‘Von des schimmernden Sees Traubengestaden her’ alongside Goethe’s own response to the mirroring waves (‘Und im See bespiegelt Sich die reifende Frucht’; ‘Die Welle wieget unsern Kahn’). Klopstock had called on joy to come, either from the grape-lined banks of the shimmering lake or (if she had already flown off back to the heavens) to come back in the increasingly red rays of the evening sun, on the wings of evening air. Stolberg’s song takes up the images of increasingly red light (Abendrot, der rötliche Schein, im errötenden Schein) and of wings (but now they are carrying us away rather than bringing joy down to us). Do we hear an echo too of Goethe’s ‘Morgenwind umflügelt Die beschattete Bucht’?

‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen’ begins with space and ends with time. The first word locates the speaker: ‘Mitten’, in the middle. Prepositions and adverbs then place him ‘on’ the waves. The sunlight comes ‘down’ and dances ‘around’ the boat. Messages come from ‘over’ the treetops of the ‘western’ wood and from ‘under’ the branches of the one in the ‘east’. The third stanza then links the movement of the waves with the beating of wings to ‘lift’ the imagery from the spatial to the temporal. The critical words are now ‘tomorrow’, ‘again’, ‘yesterday’, ‘today’, ‘change’, ‘time’. The purpose of these references to time, however, is to suggest that the experience on the water allows us to escape from it into eternity.

Klopstock’s Ode had also ended with an image of eternity, and it was this aspect of the text that Goethe had appeared to challenge in ‘Auf dem See’. We should not wait for or invoke another realm or dimension. Hier auch Lieb und Leben ist. Not many poets of his age (or any other) have been able to reject dualism so completely, and it appears that Stolberg was reasserting his ‘old-fashioned’ world view in ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen’. He continued to be inspired by Klopstock and by nature itself, but not in the way that Goethe was. In later life Stolberg converted to Catholicism and his divergence from Goethe was complete.

It will never be possible to demonstrate that Stolberg’s ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen’ makes explicit reference to Klopstock’s ‘Der Zürchersee‘ and to Goethe’s ‘Auf dem See’ (and that the text therefore indirectly refers back to the same outing in 1775), but the evidence appears strong enough to suggest at least unconscious links.

Behind two of Schubert’s most popular songs, which have lived independent lives for nearly two centuries, lies a Klopstock Ode which itself makes reference to other texts and writers. It may be this specificity (we do not know enough about Gleim and Hagedorn to respond immediately to it, perhaps) which has made it unsuitable for musical setting. Both Goethe’s and Stolberg’s echoes of Klopstock are sufficiently subtle to allow their lyrics to have an effect without readers and listeners needing to worry about intertextuality. Nevertheless, being aware of the contexts from which they emerged might help us to respond to them in new ways. After all, it was Goethe himself who encouraged us to do so when he explained the origins of ‘Auf dem See’ in his autobiography.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zürichsee_-_Halbinsel_Au_IMG_1150.JPG

☙

Original Spelling Auf dem See Und frische Nahrung, neues Blut Saug' ich aus freier Welt; Wie ist Natur so hold und gut, Die mich am Busen hält! Die Welle wieget unsern Kahn Im Rudertakt hinauf, Und Berge, wolkig himmelan, Begegnen unserm Lauf. Aug', mein Aug', was sinkst du nieder? Goldne Träume, kommt ihr wieder? Weg, du Traum! so Gold du bist; Hier auch Lieb' und Leben ist. Auf der Welle blinken Tausend schwebende Sterne, Weiche Nebel trinken Rings die thürmende Ferne; Morgenwind umflügelt Die beschattete Bucht, Und im See bespiegelt Sich die reifende Frucht.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s possible source, Goethe’s sämmtliche Schriften. Siebenter Band. / Gedichte von Goethe. Erster Theil. Lyrische Gedichte. Wien, 1810. Verlegt bey Anton Strauß. In Commission bey Geistinger page 69; with Goethe’s Werke. Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand. Erster Band. Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. 1827, page 86; and with Goethe’s Schriften, Achter Band, Leipzig, bey Georg Joachim Göschen, 1789, pages 144-145.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 69 [83 von 418] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ163965701

For Klopstock’s Ode Der Zürchersee in German, go to http://www.literaturwelt.com/werke/klopstock/zuerchersee.html

For William Taylor’s English translation of the Ode from 1828, go to http://www.lindahines.net/blog/?p=613

A version of the essay above was published in The Schubertian in July 2011