The huntsman

(Poet's title: Der Jäger)

Set by Schubert:

D 795/14

[October-November 1823]

Part of Die schöne Müllerin, D 795

Was sucht denn der Jäger am Mühlbach hier!

Bleib trotziger Jäger in deinem Revier!

Hier gibt es kein Wild zu jagen für dich,

Hier wohnt nur ein Rehlein, ein zahmes, für mich.

Und willst du das zärtliche Rehlein sehn,

So lass deine Büchsen im Walde stehn,

Und lass deine klaffenden Hunde zu Haus,

Und lass auf dem Horne den Saus und Braus,

Und schere vom Kinne das struppige Haar,

Sonst scheut sich im Garten das Rehlein fürwahr.

Doch besser, du bliebest im Walde dazu,

Und ließest die Mühlen und Müller in Ruh.

Was taugen die Fischlein im grünen Gezweig?

Was will denn das Eichhorn im bläulichen Teich?

Drum bleibe du trotziger Jäger im Hain

Und lass mich mit meinen drei Rädern allein;

Und willst meinem Schätzchen dich machen beliebt,

So wisse, mein Freund, was ihr Herzchen betrübt.

Die Eber, die kommen zu Nacht aus dem Hain

Und brechen in ihren Kohlgarten ein,

Und treten und wühlen herum in dem Feld;

Die Eber, die schieß, du Jägerheld!

So what is that huntsman looking for here by the mill river?

You troublesome hunter, stay within your own territory.

There is no game for you to chase here,

Only one little roe deer, a tame one, lives here, and she is for me.

And if you want to see that tender little roe deer

Then leave your rifle in the woods,

And leave your yapping dogs at home,

And stop making those noises on your horn,

And shave that shaggy hair off your chin,

Otherwise the little roe deer in the garden will definitely shy away from you.

But even better, just stay over there in the woods,

And leave mills and millers in peace.

What is the point of a little fish going into green branches?

Why would a squirrel go into a blue pond?

So, troublesome hunter, stay amongst the trees,

And leave me alone with my three wheels;

And if you want to make my treasure fall in love with you

Let me tell you, my friend, what bothers her little heart:

Boars come out of the woods at night

And break into her cabbage patch,

And they trample and root about in the soil:

It is those boars you should shoot, you hunting hero!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Blue Deer Dogs Fish and fishing Gardens Green Guns Horns Hunters and hunting Mills Ponds Rivers (Bach) Wheels Woods – groves and clumps of trees (Hain) Woods – large woods and forests (Wald)

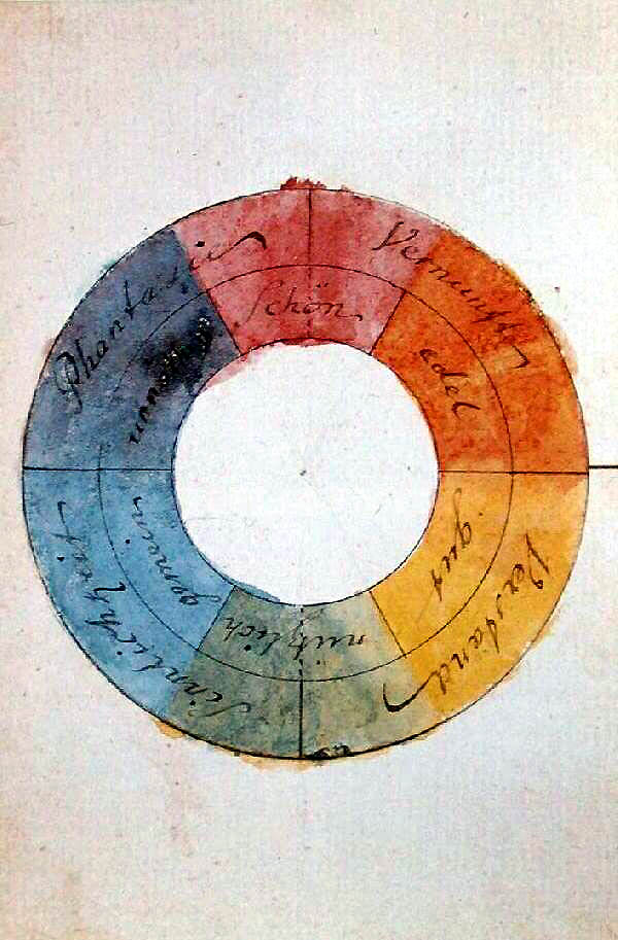

On spectra and on colour wheels (such as that produced by Goethe in 1809) green and blue are adjacent colours, not opposites. For the young miller, though, they represent two separate and inherently incompatible domains:

Was taugen die Fischlein im grünen Gezweig?

Was will den das Eichhorn im bläulichen Teich?

What is the point of a little fish going into green branches?

Why would a squirrel go into a blue pond?

He sees the green-jacketed huntsman (from the world of the green forest) as an invader in his world of blue water and blue flowers. He wants there to be clear boundaries. His beloved might be a ‘deer’, but she is domesticated and so ‘out of bounds’; she is not ‘fair game’.

The fact is that antagonisms are more common between neighbours than between polar opposites. There IS no clear boundary between green and blue, and there can be no way of isolating the river-bound life of the mill from the wider context of the surrounding woods. When the first agriculturalists settled down and planted crops they did not suddenly stop being hunter-gatherers, but a spectrum emerged and there have been tensions between the two ways of living ever since. In the context of Die schöne Müllerin the mill represents the world of cereal farming (flour production) and small-holdings (the girl’s cabbage patch), but it cannot be completely cut off from the domain of the hunter-gatherers all around. The wild boar that trample over the girl’s garden will almost inevitably end up as pork or sausages on top of a pile of sauerkraut made from the surviving cabbages.

The huntsman represents a threat to the young miller on a psychological level, too. He is perceived as being different not just because of his outsider status and his role as a huntsman but also because he seems to represent a different type of personality. He is seen as unkempt (with his untidy beard) and unpredictable (there is no pattern to the noises he makes, with his yapping dogs, his blaring horn and his loud gunshots), in contrast to the young miller’s regularity (whose activities revolve around the flowing river and the cyclical motion of the mill wheels and the grinding stone). We can be fairly certain that the miller is taciturn and withdrawn, whereas the hunter is brash and confident. As a sexual rival the huntsman exposes all of the miller’s shortcomings in terms of traditional masculinity. The miller’s poem is an attempt to rise to the challenge. He may have practised saying his piece in front of the mirror (or the river), but we have to doubt that he was ever able to pluck up the courage to deliver any of this face to face.

☙

Original Spelling Der Jäger Was sucht denn der Jäger am Mühlbach hier? Bleib', trotziger Jäger, in deinem Revier! Hier giebt es kein Wild zu jagen für dich, Hier wohnt nur ein Rehlein, ein zahmes, für mich. Und willst du das zärtliche Rehlein sehn, So laß deine Büchsen im Walde stehn, Und laß deine klaffenden Hunde zu Haus, Und laß auf dem Horne den Saus und Braus, Und scheere vom Kinne das struppige Haar, Sonst scheut sich im Garten das Rehlein fürwahr. Doch besser, du bliebest im Walde dazu, Und ließest die Mühlen und Müller in Ruh'. Was taugen die Fischlein im grünen Gezweig? Was will denn das Eichhorn im bläulichen Teich? Drum bleibe, du trotziger Jäger, im Hain, Und laß mich mit meinen drei Rädern allein; Und willst meinem Schätzchen dich machen beliebt, So wisse, mein Freund, was ihr Herzchen betrübt: Die Eber, die kommen zu Nacht aus dem Hain, Und brechen in ihren Kohlgarten ein, Und treten und wühlen herum in dem Feld: Die Eber, die schieß, du Jägerheld!

Confirmed with Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Erstes Bändchen. Zweite Auflage. Deßau 1826. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, pages 30-31; and with Sieben und siebzig Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Dessau, 1821. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, pages 31-32.

First published in a slightly different version with the title Als er den Jäger sah in Der Gesellschafter oder Blätter für Geist und Herz. Herausgegeben von F. W. Gubitz. Zweiter Jahrgang. Berlin, 1818. In der Maurerschen Buchhandlung. Montag den 1. Juni. 87stes Blatt, page 347.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 31 Erstes Bild 41 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10115224