The crusade

(Poet's title: Der Kreuzzug)

Set by Schubert:

D 932

[November 1827]

Ein Münich steht in seiner Zell

Am Fenstergitter grau,

Viel Rittersleut in Waffen hell,

Die reiten durch die Au.

Sie singen Lieder frommer Art

In schönem, ernsten Chor,

Inmitten fliegt, von Seide zart,

Die Kreuzesfahn empor.

Sie steigen an dem Seegestad

Das hohe Schiff hinan,

Es läuft hinweg auf grünem Pfad,

Ist bald nur wie ein Schwan.

Der Münich steht am Fenster noch,

Schaut ihnen nach hinaus:

»Ich bin, wie ihr, ein Pilger doch

Und bleib’ ich gleich zu Haus.

Des Lebens Fahrt durch Wellentrug

Und heißen Wüstensand,

Es ist ja auch ein Kreuzes-Zug

In das gelobte Land.«

A monk is standing in his cell

By the grey bars on his window,

Many knights in shining armour

Are riding across the meadows.

They are singing songs of a pious nature

In a beautiful, serious chorus,

Flying in the middle of them, made of delicate silk,

High up is the flag with a cross on it.

They come up to the coast and

Approach the tall ship.

It sets off on the green path,

Soon it looks as if it is only a swan.

The monk is still standing at the window,

He watches it from where he is:

“Like you, I am a pilgrim, even

Though I remain at home.

The journey of life through the treacherous waves

And the hot sands of the desert

Is also a crusade

Into the promised land.”

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Armour Boats The cross and crucifixes Deserts Flags Green Knights Not moving Nuns, monks and monasteries Pilgrims and pilgrimage The sea Ships Silk Swans Waves – Welle Windows

"Some pray, others fight, still others work" (oratores, bellatores, laboratores) Adalbero of Laon (d. 1031), quoted in Georges Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined University of Chicago Press 1980

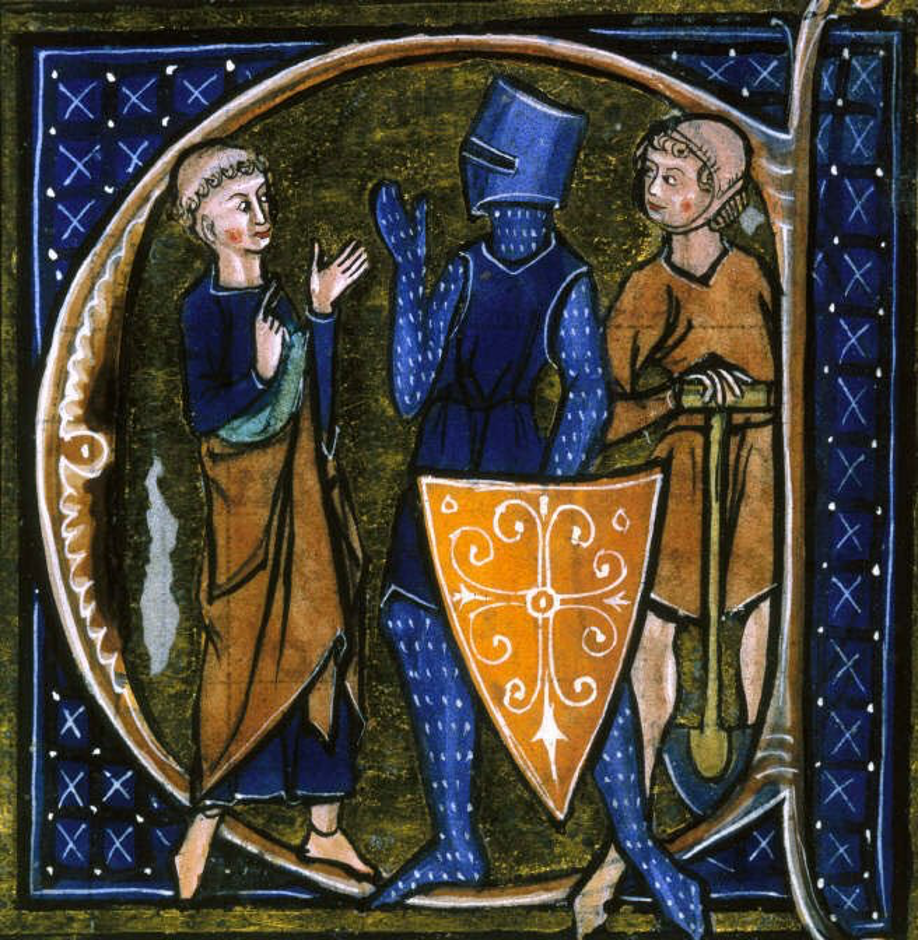

Soldiers carrying the crusading flag (a cross, hence the German name Kreuz-zug – ‘cross procession’) left northern and western Europe for the eastern Mediterranean (‘the promised land’) intermittently for about 300 years from 1096 onwards. They had taken an oath that meant that their commander in chief was the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, the Vicar of Christ on earth, and this over-rode their commitments to any other Kings and Princes whilst they were engaged in crusading activity. They were also offered a full indulgence: the promise that the external penalties for their sins would be wiped out if they died in the course of their ‘armed pilgrimage’.

This period of crusading activity corresponded with major reforms and innovations in monasticism in western Europe. Beginning with Cluny in Burgundy, there was a concern to apply the ascetic rules of the Benedictine Order more rigorously. Soon other monastic orders, most notably the Cistercians, competed to organise monasteries on more austere lines. Paradoxically, though, the further they moved into uncultivated areas and the less money they spent on personal comfort, the more economic growth they generated. The monks employed more and more farmers, who cultivated more and more land.

This was the system of the ‘three orders’. The peasants did the work on the land, which was owned either by soldiers or the church. The priests, monks and nuns prayed on behalf of everyone and were given support (in the form of tithes and other contributions) for doing so. The soldiers (the whole of the ruling class) in theory were there to protect the land and those on it from attack and predation. Many of the justifications for sending the crusading army off to fight in the Levant revolved around the idea that violence needed to be directed against the opponents of Christendom and that the military culture of Feudalism had previously encouraged too many Christians to attack each other.

Few historians of the period (often still called ‘the High Middle Ages’) would now accept the idea that society was anywhere near as unified or harmonious as this idea suggests. There is almost universal consensus that the motivation to send the Crusading Army to the eastern Mediterranean was mixed at best. Not many people would now be able to take seriously Leitner’s portrayal of a band of crusaders singing pious hymns as they calmly got on the boat. However, Leitner was writing at a time (the early 19th century) when there was an enormous desire to see Medieval Europe as a model for a balanced society, based on pure faith and the noblest of ethical principles.

This was partly a reaction to the warfare that had torn Europe apart over the previous generation. It was partly a reaction to the challenge to religious authority and institutions brought about by both the Englightenment and the French Revolution. It was partly due to an emerging belief that Europe had taken the wrong turn at the time of the Renaissance and the Reformation, both of which had fragmented society and resulted in a loss of common values and purposes. It was partly a reaction against the emerging Industrial Revolution, as people like Ruskin began to idealise an age before machine production when artisans could be true artists and everyone had their own, but equally valued, place in a simpler society.

The reaction spanned philosophy, politics, theology, history writing, literature, music, architecture and art. In all of these domains ‘Medievalism’ embodied a desire to create (they said ‘restore’) a balanced society in which people were secure in their roles. Knights could fight because they were ‘valiant’ and they were rescuing maidens in distress or protecting Christendom. Minstrels could sing because their art was appreciated by all. Monks could live in peace (remember, many in living memory had been guillotined or worse) because they were wise and their prayers were good for us all. Labourers could do their job without any need to destroy machines or form trades unions since they would feel inherently satisfied with their contribution to wider society.

The following list of works gives a flavour of the pervasiveness of these ideas about Medieval Europe in the early 19th Century:

| Date | Domain / Genre | Author | Work / Campaign |

| 1799 | Essay | Novalis | Die Christenheit oder Europa (Christendom or Europe) |

| 1802 | Philosophy | Chateaubriand | Le génie du Christianisme (The spirit of Christianity) |

| 1810 | Painting | Overbeck, Cornelius, Schnorr von Carolsfeld et al | The ‘Nazarenes’ (the ‘Lukas Bund’) begin working in an abandoned monastery in Rome producing works based on medieval rather than Renaissance models |

| 1812-1822 | History | Michaud | Histoire des Croisades [7 volumes] (History of the Crusades) |

| 1819 | Poem | Keats | La Belle Dame sans Merci |

| 1820 | Novels | Walter Scott | Ivanhoe; The Monastery |

| 1821 | Architecture | Sulpiz Boisserée | Plan for the completion of the nave and west facade of Cologne Cathedral (which inspired a Gothic revival in the Rhineland) |

| 1831 | Novel | Victor Hugo | Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482 (The Hunchback of Notre Dame) |

| 1833 | Theology and Liturgy | Pusey, Newman et al | Tracts for the Times begins the Oxford Movement (a campaign to make the Church of England an integral part of the Catholic tradition) |

| 1836 | Architecture | Pugin | Contrasts advocates a revival of Gothic architecture (this led Pugin to being commissioned to rebuild the Houses of Parliament in London in Gothic style) |

| 1845 | Opera | Wagner | Tannhäuser |

| 1848 | Painting | Hunt, Millais, Rossetti et al | The founding of the ‘pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’ |

Karl Gottfried von Leitner was from Graz, the capital of Styria, which still saw itself as on the frontline in defending Christendom from its enemies. Its mountainous terrain had meant that it was protected from the advances of the Ottoman armies across the Great Hungarian Plain in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was as if the Styrians were safe in their monastic cell looking down as their fellow Austrians (fellow Catholics, too, of course) went off to fight in defence of Christendom. Leitner, as a devout poet, must have seen himself as a modern-day monk whose life of contemplation (and whose aristocratic background) allowed him to identify with the more active ‘pilgrims’ who had fought to guarantee the security of church and state.

Ultimately, though, the poem seems to be directed at the ordinary, quiet people who have no choice but to ‘stay at home’. We all face the risk of metaphorical shipwreck as we cross the waters of life. We all risk drought as we trudge across the burning sands of the ‘desert’ that lies ahead of us. We all need to keep our eyes on the destination, that New Jerusalem that is our promised land:

And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea. And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God. And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. Revelation 21: 1 - 4 (KJV)

☙

Original Spelling Der Kreuzzug Ein Münich steht in seiner Zell' Am Fenstergitter grau, Viel Rittersleut' in Waffen hell, Die reiten durch die Au'. Sie singen Lieder frommer Art In schönem, ernsten Chor, Inmitten fliegt, von Seide zart, Die Kreuzesfahn' empor. Sie steigen an dem Seegestad' Das hohe Schiff hinan. Es läuft hinweg auf grünem Pfad, Ist bald nur wie ein Schwan. Der Münich steht am Fenster noch, Schaut ihnen nach hinaus: »Ich bin, wie ihr, ein Pilger doch Und bleib' ich gleich zu Haus'. Des Lebens Fahrt durch Wellentrug Und heißen Wüstensand, Es ist ja auch ein Kreuzes-Zug In das gelobte Land.«

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Gedichte von Carl Gottfried Ritter von Leitner. Wien, gedruckt bey J. P. Sollinger. 1825, pages 30-31; and with Gedichte von Karl Gottfried Ritter v. Leitner. Zweite sehr vermehrte Auflage. Hannover. Victor Lohse. 1857, page 264.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 30 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10113663