The busker

(Poet's title: Der Leiermann)

Set by Schubert:

D 911/24

[October 1827]

Part of Winterreise, D 911

Drüben hinterm Dorfe

Steht ein Leiermann,

Und mit starren Fingern

Dreht er, was er kann,

Barfuß auf dem Eise

Wankt er hin und her,

Und sein kleiner Teller

Bleibt ihm immer leer.

Keiner mag ihn hören,

Keiner sieht ihn an,

Und die Hunde knurren

Um den alten Mann,

Und er lässt es gehen

Alles, wie es will,

Dreht, und seine Leier

Steht ihm nimmer still.

Wunderlicher Alter,

Soll ich mit dir gehn?

Willst zu meinen Liedern

Deine Leier drehn?

Up there behind the village

Stands a busker,

And with stiff fingers

He turns the hurdy-gurdy as well as he can.

Barefoot on the ice

He sways back and forth;

And his little plate

Is always empty for him.

Nobody wants to listen to him,

Nobody looks at him;

And the dogs growl

Around the old man.

And he lets it happen

He lets everything happen as it will,

He turns the crank and his hurdy-gurdy

Is never silent for him.

Strange old man,

Shall I go with you?

Are you prepared to accompany my songs

By turning the crank on your hurdy-gurdy?

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Bards and minstrels Dogs Feet Fingers Frost and ice Journeys Songs (general) Villages Winter

For the first time in Winterreise the traveller speaks to another human being directly. There has been some furtive writing (in Gute Nacht, Der Lindenbaum and Auf der Flusse) but the only speech uttered to another being so far has been addressed to a crow (‘Krähe, wunderliches Tier, Willst mich nicht verlassen?’ / Crow, you strange animal, Do you not want to leave me?).

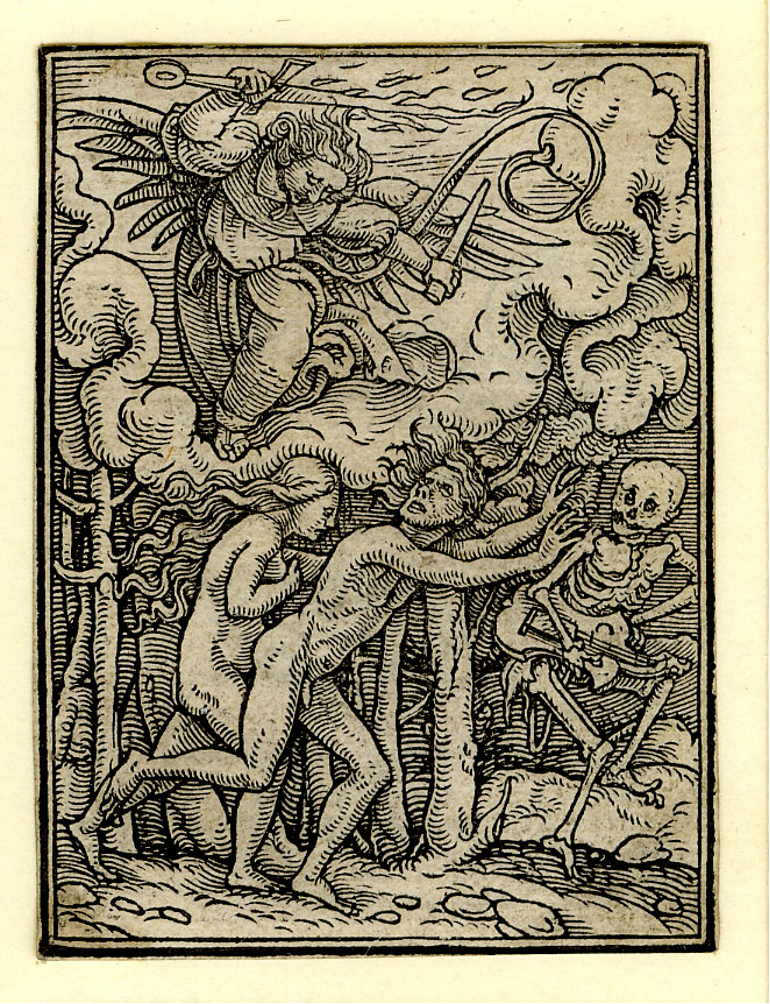

The words he chooses when speaking to the hurdy-gurdy man are in a similar form but they show that he is now ready for some sort of companionship: ‘Wunderlicher Alter, Soll ich mit dir gehn?’ (Strange old man, shall I go with you?). The old man and the crow are both ‘strange’ perhaps because they are the only creatures that do not shun his company. Or perhaps they are strange because they are uncanny and have a particularly disturbing aura. He associated the crow with death, and so the word ‘wunderlich’ had connotations of its being eerie or ominous. Some commentators have suggested that there are similar overtones with the hurdy-gurdy player, since he could be seen as a personification of Death itself. In portrayals of the dance of death in the wake of the Black Death in the 14th century skeletons were often presented as musicians leading the dance. In Holbein’s 1525 woodcut of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, death leads the way playing a hurdy-gurdy. If we read the busker as a traditional symbol of death it might explain why none of the villagers pay attention to him. His is a song they do not want to hear; they do not want to notice his presence so close to them.

Hans Holbein the younger

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1895-0122-797

Others, though, feel that this symbolic interpretation of the old man goes against the inherent sensitivity with which the poet evokes the character. He is clearly an individual rather than an allegory. What attracts the traveller (and the reader) to him is the way he keeps going despite everything. He is a figure of life rather than death. He keeps turning the wheel, despite his numb fingers, his frozen feet, the snarling dogs and the empty plate.

In many ways he represents the direct opposite of the winter traveller as a character. He stands, fixed in the same place. He has no need to keep moving. He appears to be calm and strangely contented, rather than tormented and volatile. Yet, the traveller also recognises himself in the old man. They are both outsiders but they both keep going. The wheel of the hurdy-gurdy continues to play the same drone, just as the traveller realises that he too is caught up in an endless loop. This is why it makes sense for the hurdy-gurdy to accompany the songs of the winter traveller, which he now recognises constitute a similar loop, a cycle.

In choosing to end Winterreise with Der Leiermann Müller was taking his readers back to the beginning of another cycle. We cannot hear the word ‘Leier’ without thinking of the original Greek instrument, the lyre, which gave its name to all things lyrical: the lyrics of songs, the genre of lyric poetry itself. Western poetry had developed the lyric in remarkable and complex ways, yet Müller is keen to return it to its most basic essence. He simplifies the language to such an extent that we are hardly aware that we are reading poetry, so direct and so acute is the communication. With the hurdy-gurdy, an instrument that has changed little since Medieval times, he has returned to the origins of German song. With the encounter between the traveller and the hurdy-gurdy player Müller has returned to the origins of European lyric poetry in Greek drama.

Contemporaries knew Müller as ´Greek Müller´ since he was so active in support of the Greeks in their war of independence in the 1820s. We should not overlook the fact that his concern with Greece was not just political: he wanted the spirit of the ancient Greeks to live again in our modern world. Having presented a set of poems encompassing the most pressing concerns of 19th century Europeans (alienation, atomisation, atheism etc.) Müller brings his traveller and his readers face to face with one of the Ancients, whose lyre playing can still form the most appropriate accompaniment to the latest songs.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lyre_player_Met_06.1021.188.jpg

☙

The hurdy-gurdy

Nantes Museum of Arts

https://web.archive.org/web/20150105001354/http://www.gurdypedia.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurdy-gurdy

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drehleier

Madrid Museo del Prado

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text Der Leiermann Drüben hinter'm Dorfe Steht ein Leiermann, Und mit starren Fingern Dreht er was er kann. Baarfuß auf dem Eise Wankt1 er hin und her; Und sein kleiner Teller Bleibt ihm immer leer. Keiner mag ihn hören, Keiner sieht ihn an; Und die Hunde knurren2 Um den alten Mann. Und er läßt es gehen Alles, wie es will, Dreht, und seine Leier Steht ihm nimmer still. Wunderlicher Alter, Soll ich mit dir gehn? Willst zu meinen Liedern Deine Leier drehn? 1 Schubert changed 'Schwankt' to 'Wankt' (no essential change of meaning) 2 Schubert changed 'brummen' to 'knurren' (no essential change of meaning)

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Zweites Bändchen. Deßau 1824. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, pages 107-108; and with Deutsche Blätter für Poesie, Litteratur, Kunst und Theater. Herausgegeben von Karl Schall und Karl von Holtei. Breslau 1823, bei Graß, Barth und Comp. No. XLII. 14. März 1823, page 166.

First published in Deutsche Blätter (see above) as no. 10 of the installment of Die Winterreise. Lieder von Wilhelm Müller.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 107 Erstes Bild 121 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10115225