The lime tree

(Poet's title: Der Lindenbaum)

Set by Schubert:

D 911/5

[February 1827]

Part of Winterreise, D 911

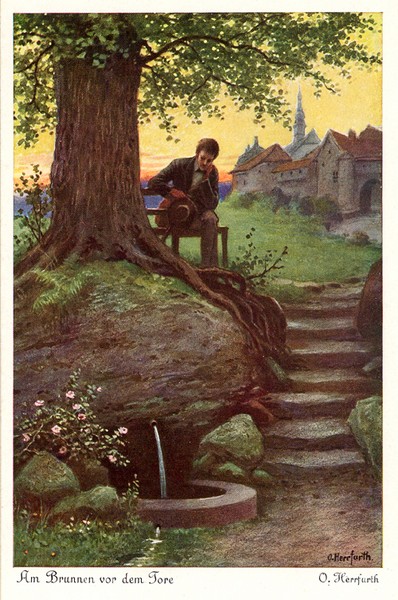

Am Brunnen vor dem Tore,

Da steht ein Lindenbaum,

Ich träumt’ in seinem Schatten

So manchen süßen Traum.

Ich schnitt in seine Rinde

So manches liebe Wort;

Es zog in Freud und Leide

Zu ihm mich immer fort.

Ich musst’ auch heute wandern

Vorbei in tiefer Nacht,

Da hab ich noch im Dunkeln

Die Augen zugemacht.

Und seine Zweige rauschten,

Als riefen sie mir zu:

Komm her zu mir, Geselle,

Hier findst du deine Ruh.

Die kalten Winde bliesen

Mir grad ins Angesicht,

Der Hut flog mir vom Kopfe,

Ich wendete mich nicht.

Nun bin ich manche Stunde

Entfernt von jenem Ort,

Und immer hör ich’s rauschen:

Du fändest Ruhe dort!

Next to the fountain in front of the gate

There is a lime tree there:

In its shade I have dreamt

So many sweet dreams.

In its bark I have carved

So many sweet words;

In joy and sorrow I have felt it pulling

Me towards itself at all times.

Today as well I had to walk

Past in the depths of night,

And there, even in the dark, I

Closed my eyes.

And its branches rustled

As if they were calling out to me:

“Come here to me, my friend,

You will find the peace you are looking for here!”

The cold winds were blowing

Straight into my face,

My hat flew off from my head,

I did not turn round.

Now I am many hours

Away from that spot,

And I can still hear the rustling:

You would find peace there!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Doors and gates Dreams Eyes Hats Journeys Joy Lime trees (Lindenbaum) Night and the moon Rest Shade and shadows Springs, sources and fountains Sweetness Walking and wandering Winter Wind

In ‘Erstarrung‘ the protagonist had worried about not being able to hold on to any memories of his beloved. By the time of ‘Der Lindenbaum’ ‘she’ has more or less disappeared, but he has no similar difficulties recalling details of the tree, which is ever present for him and which he can evoke in vivid detail. He does this not with specific description but by linking the tree to his own experience and by telling a story.

The opening line is not as informative as it looks. ‘Am Brunnen vor dem Tore’ could be interpreted in at least two ways. The tree could either be next to a fountain inside the town gate (many towns in central Germany have a tradition of building elaborate public fountains or pumps with large basins) or it could be next to a well outside the walls of the town but not far from one of the gates. We are not told how old or large the tree is (we just know that it provides shade and there is enough bark for young lads to carve graffiti in it).

The poet is not interested in the details, though. What matters is that he is setting the scene for the story to come. It is a little like the use of the lime tree in one of the fairy stories collected by the brothers Grimm (The Frog King), where the tree and the well are the essential backdrop to the narrative:

In den alten Zeiten, wo das Wünschen noch geholfen hat, lebte ein König, dessen Töchter waren alle schön; aber die jüngste war so schön, daß die Sonne selber, die doch so vieles gesehen hat, sich verwunderte, sooft sie ihr ins Gesicht schien. Nahe bei dem Schlosse des Königs lag ein großer dunkler Wald, und in dem Walde unter einer alten Linde war ein Brunnen; wenn nun der Tag recht heiß war, so ging das Königskind hinaus in den Wald und setzte sich an den Rand des kühlen Brunnens - und wenn sie Langeweile hatte, so nahm sie eine goldene Kugel, warf sie in die Höhe und fing sie wieder; und das war ihr liebstes Spielwerk. https://www.grimmstories.com/de/grimm_maerchen/der_froschkonig_oder_der_eiserne_heinrich In the olden days, when wishes still helped, there lived a King, all of whose daughters were beautiful; but the youngest was so beautiful that the sun itself, who had already seen so much, was amazed whenever it shone onto her face. Near to the King's castle lay a large, dark forest, and in the forest, under an old lime tree there was a well; and when the day had become really hot, the King's child went out into the wood and sat down on the edge of the cool well - and when she felt bored, she took a golden ball, threw it up into the air and caught it again; and that was her favourite game.

What happened next, we want to know. Müller sets up his narrative in a similar way. There was a tree where he regularly used to go, where he used to dream many a sweet dream, where he used to carve ‘loving words’ (an odd choice of phrase, perhaps). All of this is a sort of equivalent to the princess playing with the golden ball. The reader is prompted to ask, ‘Then what happened?’

What happened is this. He had to walk past that tree last night, but even though it was dark he closed his eyes so that he could not see it. Then he heard the rustling of the leaves (it was mid-winter, remember, the path and the fields were covered in snow, so we are expected to be surprised by this). In that rustling the tree was speaking to him directly. It addressed him as ‘Geselle’ (‘mate’ or ‘companion’) and it offered a resting place. However, he chose not to respond. The wind blew more fiercely and he lost his hat. He decided not to turn round. It is only now, at the moment of telling the story that he can bring himself to look back. A number of hours later and who knows how many miles past the tree, he can still hear those non-existent leaves rustling and speaking to him. The words have changed slightly, though. There is no longer a promise (‘You will or can find rest here’), just speculation or (perhaps) reproach (‘If you came back here, you might find peace’ / ‘You could have been at rest now if you had stayed here’).

So, why did he not stop? Why did he close his eyes? Why did he not turn back when the wind blew his hat off? What was the lure of the tree that he was working so hard to resist?

It must be something to do with what it had offered him previously, something that on this occasion he was determined to renounce: shade, shelter, the opportunity to dream and to fantasise, escapism. All of that, he has now decided, belongs to his previous life. It is time to escape escapism. He has left the shelter of a real roof in the middle of the night, so he is not going to make use of the canopy of a tree to protect himself from the elements. When the wind blows his hat off he does not even turn round to recover it: he has decided to live without that sort of artificial protection from the elements.

So his decision to close his eyes was in effect a decision to open his eyes to the reality of the world, a reality that he has previously ignored. The voice of the lime tree is a siren call from the land of fantasy, the world of fairy stories. It also represents a way of coping with the constraints and restrictions of conventional small-town life, with its offer of rest under the shade with water nearby. He has decided to leave. He therefore ‘had to’ walk past that tree. He had to resist the temptation to rest. He is on a journey that is not leading to a resting place, even the conventional resting place of a grave.

☙

Comments and other points of view

Malcolm, This is a curious, semi-opaque poem, and I enjoy your exposition very much. The fairy tale reference is clever intuition on your part. There is a curious dream-like quality to this little scene, a frightening dream like a child imagining a fearful place at night. I had such places when I grew up – particular trees or tall hedges that cast shadows, the completely black passage to our back door. And a certain short road, a cul de sac, in the posher part of town which wound uphill slightly between mature trees. I used to have a recurring dream of wandering up there at night, the trees thrashing in the wind so you could not tell if another person was there. I approach an opening white gate to a house I did not know, nor why I might be there. I never go through the gate. It always ends on my approach. Yes, it is hard not to feel in Der Lindenbaum some idea of gaining maturity, leaving childish things behind, the home place – like as you say, ‘every’ German town would have its gate, its fountain and linden tree. The tree on the green for an English person, Grantchester church clock. He must travel on, in darkness, even houseless (hatless), afraid to be where he is but afraid that going back is like death or never-having-lived. You must identify with this quite strongly - ? The urge to move out into the world – the gate has two sides, two worlds. Which will you choose? The living death of staying put, or the fearful adventure ‘out there’? Interesting that the home place is always the past, old-fashioned, set in its ways, etc. Interesting that Shakespeare ran away with the circus, so to speak, from his small town to the big city and his destiny – then (like many a writer) wrote about it almost all his life, including his home woods and fields. /.. There is a fascinating Italian folk-tale rendered by Italo Calvino about a man who lives forever, so long as he keeps moving on his horse and does not set his foot on the ground. But returning he sees all of the past gone, everywhere he knows; there is nothing he can recognise or attach to. For a reason I can’t remember he is tricked into stepping down from his horse and immediately death grabs him. In Der Lindenbaum he seems afraid he will never escape if he ‘listens’ to the tree. But it calls to him with a promise of ‘rest’. I know the lure of the home town and that it means ‘giving in’. John

Original Spelling Der Lindenbaum Am Brunnen vor dem Thore Da steht ein Lindenbaum: Ich träumt' in seinem Schatten So manchen süßen Traum. Ich schnitt in seine Rinde So manches liebe Wort; Es zog in Freud' und Leide Zu ihm mich immer fort. Ich mußt' auch heute wandern Vorbei in tiefer Nacht, Da hab' ich noch im Dunkeln Die Augen zugemacht. Und seine Zweige rauschten, Als riefen sie mir zu: Komm her zu mir, Geselle, Hier findst du deine Ruh'! Die kalten Winde bliesen Mir grad' in's Angesicht, Der Hut flog mir vom Kopfe, Ich wendete mich nicht. Nun bin ich manche Stunde Entfernt von jenem Ort, Und immer hör' ich's rauschen: Du fändest Ruhe dort!

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Zweites Bändchen. Deßau 1824. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, pages 83-84; and with Urania. Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1823. Neue Folge, fünfter Jahrgang. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus. 1823, pages 214-215.

First published in Urania (see above) as no. 5 of Wanderlieder von Wilhelm Müller. Die Winterreise. In 12 Liedern.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 214 Erstes Bild 252 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10312443