The treasure-digger

(Poet's title: Der Schatzgräber)

Set by Schubert:

D 256

[August 19, 1815]

Arm am Beutel, krank im Herzen,

Schleppt´ ich meine langen Tage.

Armut ist die größte Plage,

Reichtum ist das höchste Gut!

Und zu enden meine Schmerzen,

Ging ich, einen Schatz zu graben.

Meine Seele sollst du haben!

Schrieb ich hin mit eignem Blut.

Und so zog ich Kreis´ um Kreise,

Stellte wunderbare Flammen,

Kraut und Knochenwerk zusammen:

Die Beschwörung war vollbracht.

Und auf die gelernte Weise

Grub ich nach dem alten Schatze,

Auf dem angezeigten Platze.

Schwarz und stürmisch war die Nacht.

Und ich sah ein Licht von weiten;

Und es kam, gleich einem Sterne,

Hinten aus der fernsten Ferne,

Eben als es zwölfe schlug.

Und da galt kein Vorbereiten.

Heller ward’s mit einem Male

Von dem Glanz der vollen Schale,

Die ein schöner Knabe trug.

Holde Augen sah ich blinken

Unter dichtem Blumenkranze;

In des Trankes Himmelsglanze

Trat er in den Kreis herein.

Und er hieß mich freundlich trinken;

Und ich dacht´: Es kann der Knabe,

Mit der schönen lichten Gabe,

Wahrlich nicht der Böse sein.

Trinke Mut des reinen Lebens!

Dann verstehst du die Belehrung,

Kommst, mit ängstlicher Beschwörung,

Nicht zurück an diesen Ort.

Grabe hier nicht mehr vergebens.

Tages Arbeit! Abends Gäste!

Saure Wochen! Frohe Feste!

Sei dein künftig Zauberwort.

Poor in the purse, sick at heart,

I pulled myself through long days.

Poverty is the greatest nuisance,

Being rich is the highest good!

And, in order to put an end to my sorrows,

I went to dig for treasure.

“You shall have my soul!”

I wrote it down in my own blood.

And so I drew circles around circles,

Arranged amazing flames,

Herbs and things made of bone all together:

The charm was completed.

And in a learned manner

I started digging for ancient treasure

In the specified place;

It was a dark and stormy night.

And I saw a light in the distance,

And it came like a star

From behind from the furthest distance

Just as it was striking twelve.

And then with no warning:

All of a sudden it became brighter

Shining out of a full bowl

That was being carried by a beautiful boy.

I saw beauteous eyes flashing

Underneath a thick garland of flowers;

In the heavenly glow of the drink

He stepped into the circle.

And in a friendly way he invited me to drink;

And I thought, “It is not possible that this lad

With his lovely gift of light

Can really be the devil.”

“Drink the courage of pure life!

Then you will understand the teaching.

Do not come back, with anxious conjuring,

Do not come back to this place.

No longer dig here in vain:

A day’s work! Guests in the evening!

Tough weeks! Jolly festivals!

Let this be your magic spell in the future.”

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Banquets and feasts Black Blood Bones and skeletons Circles Clocks Courage Cups and goblets The devil Digging Drinking Evening and the setting sun Eyes Fire Flowers Hearts Herbs Light Magic and enchantment Midnight Money Near and far Night and the moon Oaths and swearing Pain Soul Stars Storms Striking and hitting Treasure and jewels Wreaths and garlands

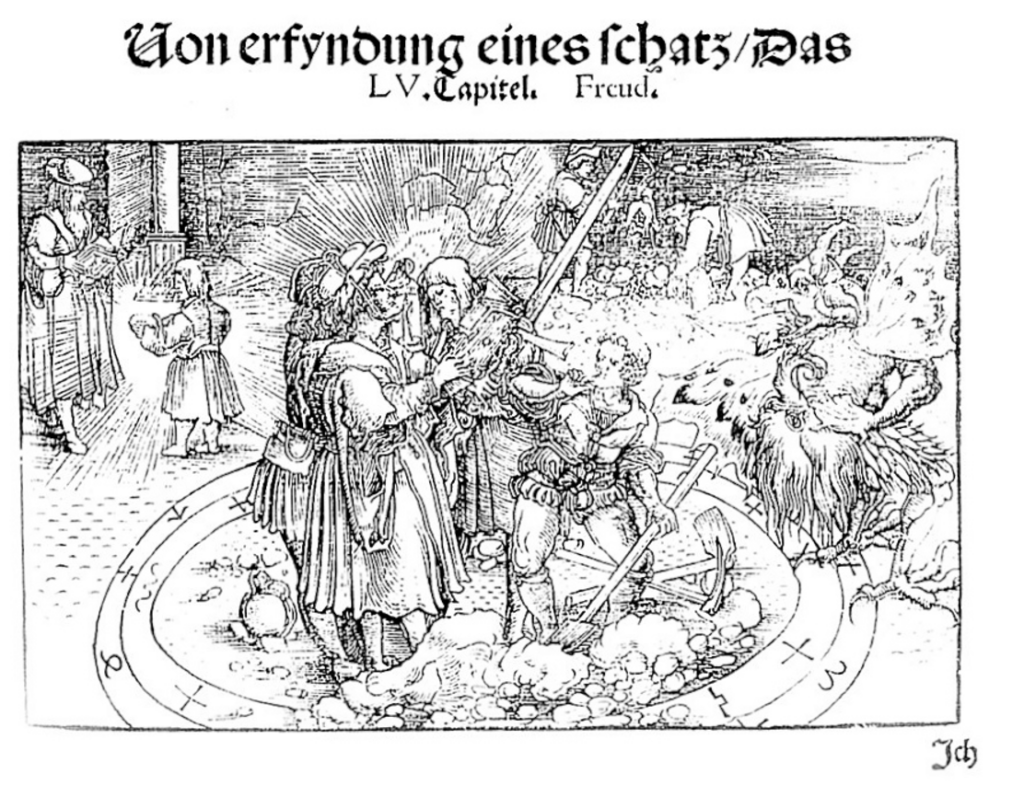

In maritime nations such as England, Spain and the Netherlands digging for buried treasure is associated with tropical islands and pirates, but in the German speaking lands it is much more connected with the occult and black magic. Goethe’s immediate inspiration for writing this text, first published in Schiller’s Musen-Almanach for 1798 along with other major ballads, was a woodcut that he saw in a 1532 German translation of Petrarch’s De remidiis, which highlights the occult nature of the process.

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b22000574/f60.item

Here the protagonist is hard at work digging (using a shovel, a pick-axe and a mattock) within a magic circle. There are three other men within the circle, one of whom seems to be holding up a long sword, presumably as part of the spell or incantation that is being read out from a large book by one of the other figures. On the edge of the circle stands the devil, breathing fire onto the head of the person digging. At the other side of the picture a small boy carries something glowing towards a standing figure reading a second book.

Goethe managed to simplify the image considerably to construct his ballad. We concentrate on the treasure-digger himself, who takes us into the story by a simple statement of his motivation: physical poverty and mental distress. No more justification is needed to explain why someone would sign a pact with the devil in their own blood: ‘my soul in return for uncovering hidden riches’. The paraphernalia of the woodcut image appear briefly in the second stanza: circles, flames, things made of bone, incantations and spells (the ‘learned manner’ he used must be related to the impressive old books that appeared in the image), but the scene is less cluttered so we can concentrate on the speaker’s own activity.

We assume that he is alone. He is certainly surprised when a light seems to appear ‘from the furthest distance’ and is then in front of him as midnight strikes. He realises that what had seemed like a star is in fact the glow from a bowl or chalice being presented to him by a beautiful boy. He is being offered the opposite of the Black Mass that he thought he was engaged in. He can now drink the light from a pure chalice. Here is the glowing treasure that he had not realised he was in search of.

The moral lesson seems obvious but is of course extremely hard to learn. There is no short cut to riches or to inner happiness. Life is hard; there is no free lunch (or buried treasure). Evenings with guests can be pleasant, but they are a reward for a day’s work. Occasionally we might have fun, but that is only possible because there are long dreary weeks of slog. Work hard; play hard. If there is any magic formula this very banal and non-magical motto is it.

It is tempting to read this change of attitude on the part of the treasure-digger in the light of Goethe’s own life and of his major work, Faust. As a supporter of the Enlightenment and a Freemason Goethe can be seen as involved in ‘hidden mysteries’, digging for buried secrets that are only accessible through esoteric activities and deep learning. Similarly, Faust in Part One of the play is on a quest to understand the heights and depths of the universe and the human soul. He too signs in blood. However, as they aged both Faust and his creator changed. In a way they transformed their approach to where enlightenment was to be found. In Part Two of Faust, the focus is on ordinary human activity; he gets involved in digging and building dykes to reclaim land from the sea rather than conjuring spirits. Goethe similarly spent a great deal of time after he moved to Weimar supervising building works and directing mining activities. He found value in the everyday realm of sheer hard work rather than in obscure divination.

Goethe’s interests in mining were always connected with his passion for geology and an attempt to understand the nature of physical reality. His work in this area corresponded with the stage in scientific development when the old occult-inclined tradition of alchemy turned into a more analytical discipline: chemistry. The narrator of Der Schatzgräber starts out as an alchemist, arranging his bones, herbs and flames in ways that could have been specified by Paracelsus or John Dee, but by the end of the poem he has come to a more down-to-earth understanding of the nature of the elements and of life itself, an approach that might reflect the latest breakthroughs in chemistry, those of Lavoisier and Dalton. Certainly as Goethe grew older his own writings about the physical world (such as Elective Affinities, which tries to explore the connection between chemical bonding and human attraction) become less learned or occult and more universal and humane. If, as some sources report, his dying words really were “More light” he might not have been making a profound observation, he might just have been asking someone to open the curtains.

☙

Original Spelling Der Schatzgräber Arm am Beutel, krank am Herzen, Schleppt´ ich meine langen Tage. Armuth ist die größte Plage, Reichtum ist das höchste Gut! Und, zu enden meine Schmerzen, Ging ich, einen Schatz zu graben. Meine Seele sollst du haben! Schrieb ich hin mit eignem Blut. Und so zog´ ich Kreis´ um Kreise, Stellte wunderbare Flammen, Kraut und Knochenwerk zusammen: Die Beschwörung war vollbracht. Und auf die gelernte Weise Grub ich nach dem alten Schatze Auf dem angezeigten Platze: Schwarz und stürmisch war die Nacht. Und ich sah ein Licht von weiten, Und es kam gleich einem Sterne Hinten aus der fernsten Ferne, Eben als es zwölfe schlug. Und da galt kein Vorbereiten. Heller ward's mit einemmale Von dem Glanz der vollen Schale, Die ein schöner Knabe trug. Holde Augen sah ich blinken Unter dichtem Blumenkranze; In des Trankes Himmelsglanze Trat er in den Kreis herein. Und er hieß mich freundlich trinken; Und ich dacht´: es kann der Knabe Mit der schönen lichten Gabe Wahrlich nicht der Böse sein. Trinke Muth des reinen Lebens! Dann verstehst du die Belehrung, Kommst, mit ängstlicher Beschwörung, Nicht zurück an diesen Ort. Grabe hier nicht mehr vergebens. Tages Arbeit! Abends Gäste; Saure Wochen! Frohe Feste! Sey dein künftig Zauberwort.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Goethe’s sämmtliche Schriften. Siebenter Band. / Gedichte von Goethe. Erster Theil. Lyrische Gedichte. Wien, 1810. Verlegt bey Anton Strauß. In Commission bey Geistinger, pages 291-292; with Goethe’s Werke, Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand, Erster Band, Stuttgart und Tübingen, in der J.G.Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, 1827, pages 198-199; and with Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1798, herausgegeben von Schiller. Tübingen, in der J.G.Cottaischen Buchhandlung, pages 46-48.

Goethe wrote the text on 21st and 22nd May 1797

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 291 [305 von 418] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ163965701