The signpost

(Poet's title: Der Wegweiser)

Set by Schubert:

D 911/20

[October 1827]

Part of Winterreise, D 911

Was vermeid ich denn die Wege,

Wo die andern Wandrer gehn,

Suche mir versteckte Stege

Durch verschneite Felsenhöhn?

Habe ja doch nichts begangen,

Dass ich Menschen sollte scheun,

Welch ein thörichtes Verlangen

Treibt mich in die Wüsteneien?

Weiser stehen auf den Wegen,

Weisen auf die Städte zu,

Und ich wandre sonder Maßen,

Ohne Ruh, und suche Ruh.

Einen Weiser seh ich stehen

Unverrückt vor meinem Blick,

Eine Straße muss ich gehen,

Die noch Keiner ging zurück.

So why am I avoiding the paths

Where the other travellers go,

Why do I search out hidden pathways for myself

Across the snow-covered rocky heights?

The fact is I am not guilty of anything

That would result in me having to shun people –

What foolish desire is it that is

Driving me into these wastelands?

Signposts stand on the paths

Pointing towards the towns,

And I keep on going

Without rest, and I am looking for rest.

I can see a signpost standing

Motionless before my eyes;

I have to go down a street

That nobody has yet returned from.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Gazes, glimpses and glances Journeys Mountains and cliffs Paths Rest Snow Towns Walking and wandering Winter

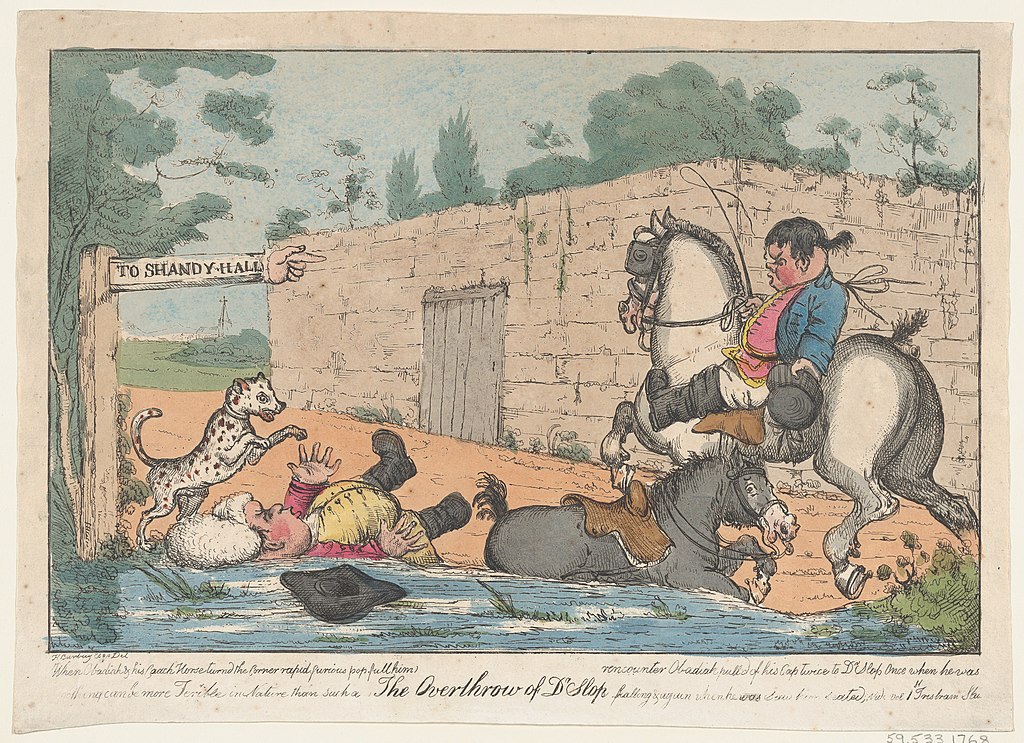

Thomas Rowlandson, 1st May 1812

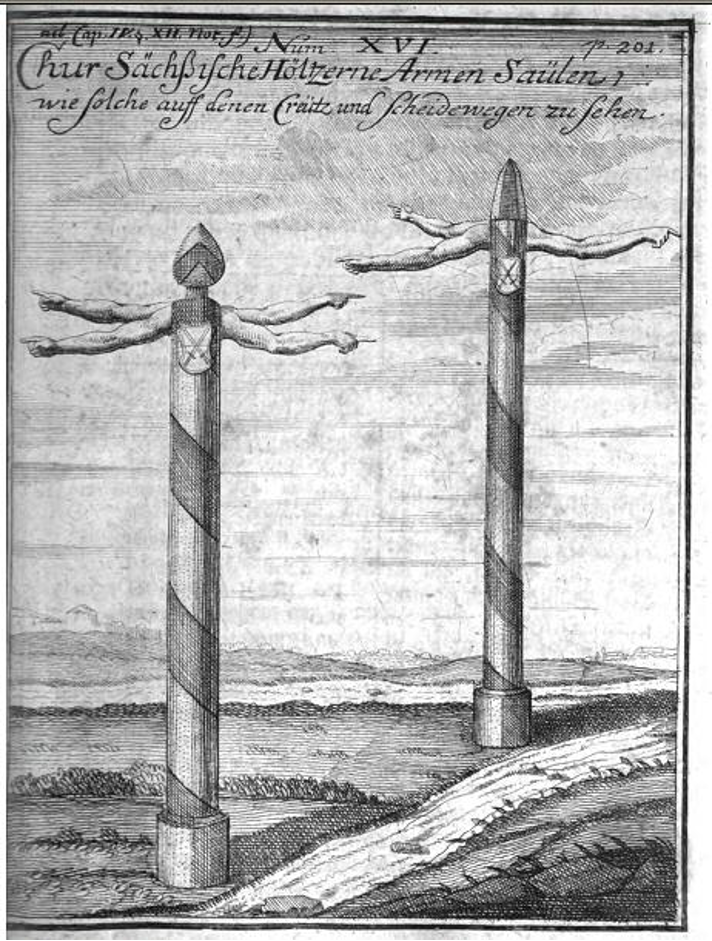

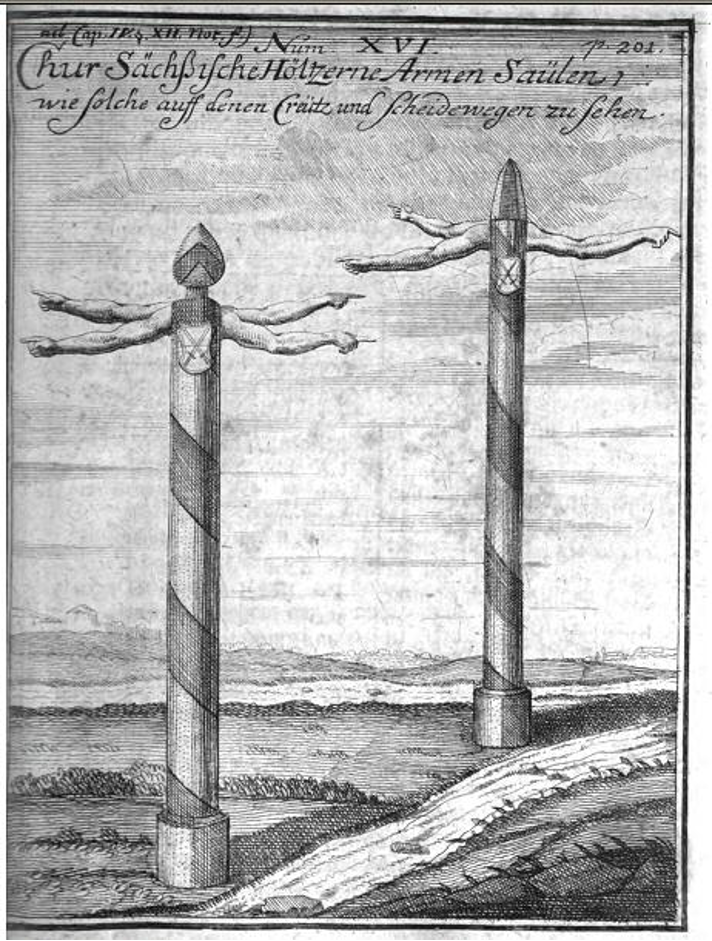

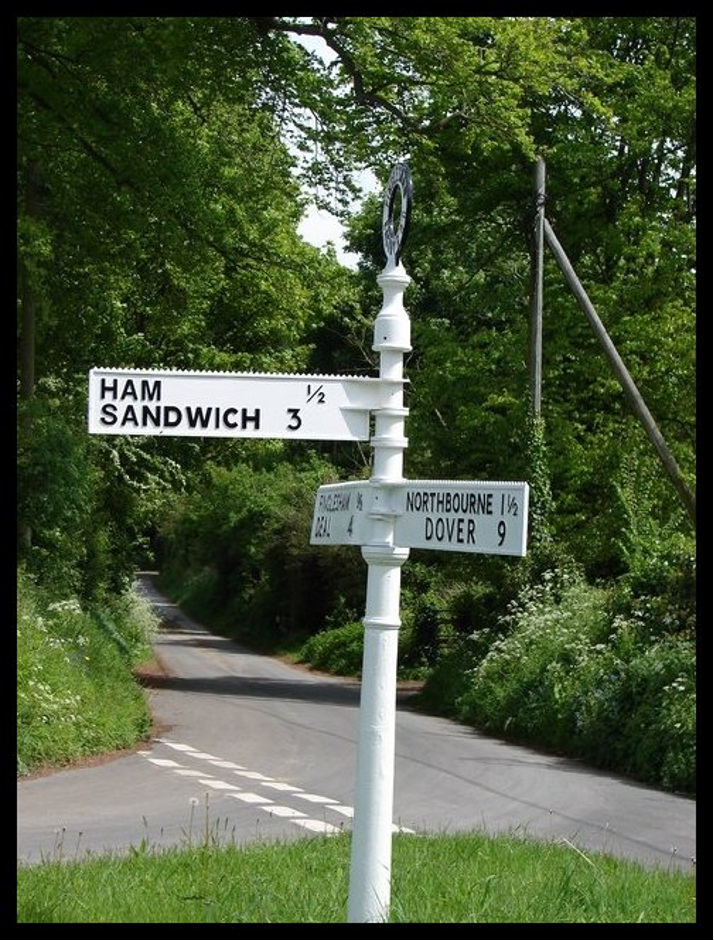

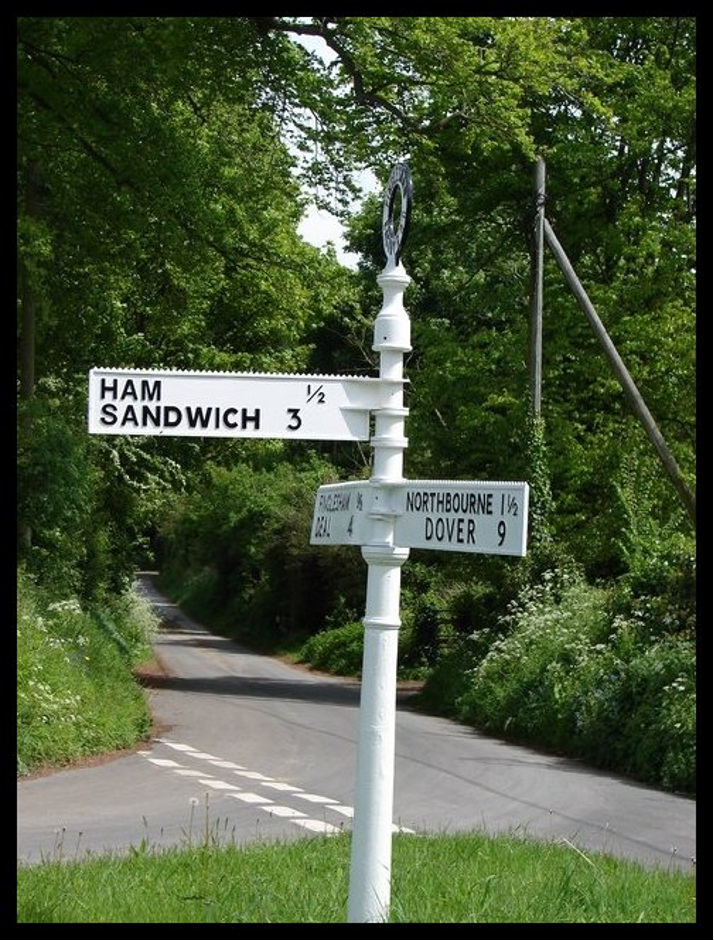

The verb ‘weisen’ means ‘to show’, ‘to indicate’ or ‘to point’, so a ‘Wegweiser’ is something that shows or points the way. Signposts used to make this explicit by including fingers (or even whole arms) to point towards the destination. However, most travellers through most of human history were illiterate and so they could not read signposts: they had to ask the way from people they encountered. Early signposts therefore were seen as taking the place of real people who knew their way around. The activity of pointing or indicating was related to the fact that they were knowledgeable, that they were ‘wise’ (the adjective ‘weise’ and the verb ‘weisen’ are both cognate with ‘wissen’ / ‘to know’).

Our traveller thus sees (or imagines) a signpost and responds by asking himself questions. What does he know about his own journey? Why is he avoiding the beaten track? What is driving him away from the usual routes and destinations? What knowledge does HE have that allows him to set his own course, to be himself a ‘Wegweiser’ – someone who can point the way?

We soon realise, of course, that these are not questions about cartography and topography, but about life itself. They are more about ‘why’ than ‘where’. They require answers that belong to the domain of wisdom rather than simple knowledge.

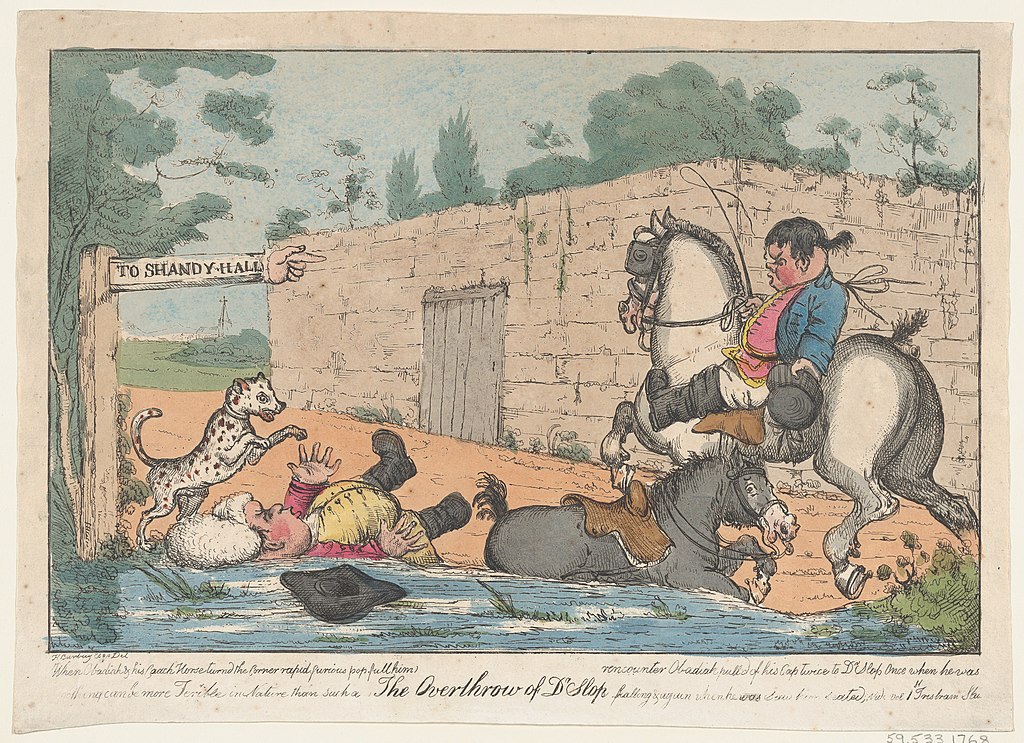

Walkers in southern Germany and Switzerland are familiar with the signposts that do not just give the directions but predict precisely how long it will take to get to the destination. It is not just that everyone is expected to go the same way (and not stray from the path), but they are also expected to go at roughly the same pace. The route and the journey are predictable. Others have done it (in both directions), others are doing it and there is no reason for future travellers not to do it. It is precisely this predictability that the winter traveller wants to avoid. The signpost that he has decided to follow directs him down a route that nobody has ever returned from.

The paradox is that this is the most beaten track of all. We are all on a journey to death. What our traveller realises, though, is that he has to take responsibility for setting his own course towards the grave, that his journey cannot and should not fit into a general pattern. His restless search for rest is his alone, but it is all encompassing.

☙

For more on fingerposts and signposts: https://www.sabre-roads.org.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Fingerpost and https://www.milestonesociety.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/On-The-Ground-Volume-4-Full-Issue.pdf

Thomas Rowlandson, c.1803

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Der Wegweiser Was vermeid' ich denn die Wege, Wo die andern Wandrer gehn, Suche mir versteckte Stege Durch verschneite Felsenhöhn? Habe ja doch nichts begangen, Daß ich Menschen sollte scheun - Welch ein thörichtes Verlangen Treibt mich in die Wüsteneien? Weiser stehen auf den Wegen1, Weisen auf die Städte zu, Und ich wandre sonder Maßen, Ohne Ruh', und suche Ruh'. Einen Weiser seh' ich stehen Unverrückt vor meinem Blick; Eine Straße muß ich gehen, Die noch Keiner ging zurück. 1 Schubert changed 'Straßen' (streets) to 'Wegen' (routes or paths)

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Zweites Bändchen. Deßau 1824. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, page 97; and with Deutsche Blätter für Poesie, Litteratur, Kunst und Theater. Herausgegeben von Karl Schall und Karl von Holtei. Breslau 1823, bei Graß, Barth und Comp. No. XLII. 14. März 1823, page 165.

First published in Deutsche Blätter (see above) as no. 7 of the installment of Die Winterreise. Lieder von Wilhelm Müller.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 97 Erstes Bild 111 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10115225