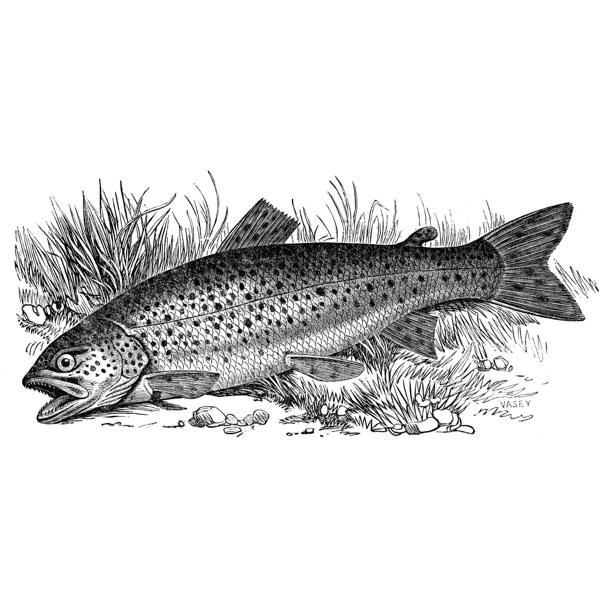

The trout

(Poet's title: Die Forelle)

Set by Schubert:

D 550

Schubert did not set the stanza in italics[1817?]

In einem Bächlein helle,

Da schoss in froher Eil

Die launische Forelle

Vorüber wie ein Pfeil.

Ich stand an dem Gestade

Und sah in süsser Ruh

Des muntern Fischleins Bade

Im klaren Bächlein zu.

Ein Fischer mit der Rute

Wohl an dem Ufer stand

Und sah’s mit kaltem Blute,

Wie sich das Fischlein wand.

So lang dem Wasser Helle,

So dacht’ ich, nicht gebricht,

So fängt er die Forelle

Mit seiner Angel nicht.

Doch endlich ward dem Diebe

Die Zeit zu lang, er macht

Das Bächlein tückisch trübe,

Und eh ich es gedacht,

So zuckte seine Rute,

Das Fischlein zappelt dran,

Und ich mit regem Blute

Sah die Betrogne an.

Ihr, die ihr noch am Quelle

Der sichern Jugend weilt,

Denkt doch an die Forelle;

Seht ihr Gefahr, so eilt!

Meist fehlt ihr nur aus Mangel

Der Klugheit; Mädchen, seht

Verführer mit der Angel –

Sonst blutet ihr zu spät.

In a bright little stream

Shooting past in carefree haste

Was a capricious trout,

Going off like an arrow:

I stood by the edge of the water

And in sweet peace I watched

The lively little fish as it bathed

In the clear little stream.

A fisherman with his rod

Was standing on the bank, though,

And cold bloodedly he watched

As the little fish twisted.

So long as the bright water

Is not disturbed, I thought,

He won’t be able to catch the trout

With his fishing rod.

But in the end the thief felt

That it was taking too long; he made

The little stream treacherously cloudy:

Before I realised it,

His rod started twitching;

The little fish wriggled about on it;

And I, with my blood boiling,

Watched on as she was tricked.

Those of you who are still near the source

Of confident youth, waiting there,

Remember that trout;

When you see danger, then hurry away!

The main danger for you is a lack

Of wisdom; Girls, look out for

Seducers with their rods –

Otherwise it will be too late and you will bleed.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Anger and other strong emotions Blood Bows and arrows By water – river banks Catching Fish and fishing Rivers (Bächlein) Rough and smooth Thieves and robbers Time Trouts

In 1785, when this poem was first published in Gedichte aus dem Kerker (Poems from inside the prison cell), the author was one of the most famous political prisoners in Europe. Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739 – 1791) had angered Duke Karl Eugen of Würtemburg by criticising his policy of hiring out mercenaries to fight for the British crown in the American War of Independence. His polemics and satires against the Jesuits and the Duke’s mistress were the final straw. Schubart had been writing within the safety of the Imperial Free Cities of Augsburg and Ulm, where the Duke’s authority held no sway, but on 23rd January 1777 the poet fell into the Duke’s trap. He was lured to the monastery of Blaubeuren (technically part of Würtemburg), where he was arrested and then imprisoned without trial. For the first few years he was allowed no books or writing materials, but he was eventually allowed to write after his case was taken up by famous supporters, such as Herder and Schiller.

So, who is the trout and who is the angler? Clearly the poet knew what it was to be tricked and caught, so it is tempting to see him as the victim and the Duke as the thieving and deceitful fisherman. Yet the fact that Schubart was now able to write and publish the poem suggests that it is the Duke who is being outsmarted and who is squirming on the end of the line.

One way in which Schubart is playing with the Duke is through the easy deniability that the poem has anything whatsoever to do with the biographical and political background which has just been outlined. Although the text appeared in a collection of ‘poems written in a dungeon’, on the surface it is simply a moralising warning to young women about the dangers represented by men and their rods. This is reinforced in the original context by its following on from a poem about the risk to women of falling for soldiers, ‘Warnung an die Mädels‘ (Warning to Girls).

The trout is presented as female (‘eine Forelle’ is a feminine noun in German) and is given the traditional attributes of a slippery, fishy woman. She is ‘capricious’ and ‘jolly’ or ‘carefree’, yet she is easily tricked. She might wriggle when she is caught but she has to submit to her more powerful captor. The angler is presented as a strong, active figure who can outwit her. He is cold-blooded and patient when necessary, but decisive and imposing when it is time to go in for the kill. Alongside these two protagonists is the narrator, who clearly takes the side of the fish, despite describing her as capricious and slippery. By the end of the story his detached observation has given way to anger; his blood is said to be raging or boiling, in contrast to the cold-blooded angler. It is this anger which provokes his warning to women in the final strophe.

Or is he angry with himself for allowing himself to be tricked? Like the trout, he used to inhabit a ‘clear’ environment. In the culture of the Enlightenment Schubart had been able to write straightforwardly. His polemics were sharp and direct (‘like an arrow’). For as long as the water was not disturbed he felt safe in that world, but then the waters were muddied. He lost the clarity that he had known and was tricked. He is therefore writing now as an older, wiser man, reflecting on the loss of youth and the self-confidence that goes with it.

Although on the surface the poem is therefore a straightforward morality tale about the dangers lying in wait for the innocent, the fact that this is a poem with different points of view and shifting emphases means that there are complexities hidden within it. Can we trust this narrator? Are we ourselves being tricked in some sense? If we are intended to learn from this older man’s experience of trickery why should we venerate simple ‘innocence’? The polarities on which the text is based cannot be reduced to a simple good vs. evil scenario:

clear - opaque female - male direct - devious watching - acting calm - agitated innocence - experience youth - age

Although the stream is said to be ‘clear’ at the beginning of the text, the purpose of the story is not.

☙

Original Spelling and notes on the text Die Forelle In einem Bächlein helle, Da schoß in froher Eil Die launische Forelle Vorüber, wie ein Pfeil: Ich stand an dem Gestade, Und sah' in süsser Ruh Des muntern Fischleins1 Bade Im klaren Bächlein zu. Ein Fischer mit der Ruthe Wol an dem Ufer stand, Und sah's mit kaltem Blute Wie sich das Fischlein wand. So lang dem Wasser Helle, So dacht' ich, nicht gebricht, So fängt er die Forelle Mit seiner Angel nicht. Doch endlich2 ward dem Diebe Die Zeit zu lang; er macht Das Bächlein tückisch trübe: Und eh' ich es gedacht, So zuckte seine Ruthe; Das Fischlein zappelt dran; Und ich, mit regem Blute, Sah die Betrogne an. Ihr, die ihr noch am Quelle3 Der sichern Jugend weilt, Denkt doch an die Forelle; Seht ihr Gefahr, so eilt! Meist fehlt ihr nur aus Mangel Der Klugheit; Mädchen, seht Verführer mit der Angel - Sonst blutet ihr zu spät. 1 Schubert changed the poet's 'Fisches' (the fish) to 'Fischleins' (the little fish) 2 In later editions of his poems Schubart changed 'endlich' (in the end) to 'plözlich' (suddenly) 3 In later editions of his poems Schubart changed this line to 'Die ihr am goldnen Quelle' (Those of you who are still near the golden source) Schubart, who set the poem himself, had an additional stanza (between stanza 3 and 4) which he supressed in the printed edition: So scheust auch manche Schöne Im vollen Strom der Zeit Und sieht nicht die Sirene Die ihr im Wirbel dräut. Sie folgt dem Drang der Liebe Und eh' sie sichs versieht So wird das Bächlein trübe Und ihre Unschuld flieht.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, Chr. Daniel Friedrich Schubarts Gedichte aus dem Kerker. Mit allerhöchst-gnädist Kaiserl. Privilegio. Carlsruhe, bey Christian Gottlieb Schmieder 1785, pages 228-229; with Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubarts sämtliche Gedichte. Von ihm selbst herausgegeben. Zweiter Band. Stuttgart, in der Buchdruckerei der Herzoglichen Hohen Carlsschule, 1786, pages 139-140; and with Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart’s Gedichte. Herausgegeben von seinem Sohne Ludwig Schubart. Zweyter Theil. Frankfurt am Main 1802, bey J. C. Hermann, pages 302-303.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 228 [244 von 324] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ200860409