The post

(Poet's title: Die Post)

Set by Schubert:

D 911/13

[October 1827]

Part of Winterreise, D 911

Von der Straße her ein Posthorn klingt.

Was hat es, dass es so hoch aufspringt,

Mein Herz?

Die Post bringt keinen Brief für dich,

Was drängst du denn so wunderlich,

Mein Herz?

Nun ja, die Post kommt aus der Stadt,

Wo ich ein liebes Liebchen hatt’,

Mein Herz!

Willst wohl einmal hinüber sehn,

Und fragen, wie es dort mag gehn,

Mein Herz?

I can hear the sound of a posthorn coming from the street.

What is it about it that it leaps up so high,

My heart?

The post is not bringing any letter for you,

So why are you driven in such a strange way,

My heart?

Of course, the post is coming from the town

Where I used to have a beloved darling,

My heart!

Is it just that you want to go over

And ask how things are going there,

My heart?

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Hearts Horns Horses Journeys Leaping and jumping Letters and correspondence Riding – carriages Riding – on horseback Towns Winter

It is hardly surprising that the heart leaps at the sound of a posthorn. The call itself probably began with a leaping octave on the (valveless) horn, and it is almost impossible for listeners’ spirits not to rise with the music. For anyone desperate for news or expecting a letter, hopes rise too. However, our traveller knows that the call was not intended for him, that any letters being carried are not addressed to him. Or rather, his head knows this; his heart does not, which is why this poem is written as a series of questions directed at a part of himself that he is finding mysterious and over which he has no control.

As with the image of the outsider passing along without exchanging greetings with anyone in ‘Einsamkeit’, the idea of other people receiving letters is surprisingly effective in conveying isolation and alienation. The traveller is avoiding the beaten track (he hears the horn ‘from the street’, not while he is on it). The world with all of its day to day activity is passing him by. Only his heart keeps some sort of emotional attachment to the past and the distant town that he is trying to escape from, which means that certain sounds can trigger an alarmingly immediate response.

Müller had used a similar horn call to emphasise the protagonist´s alienation in Die schöne Müllerin. In that case (in Die böse Farbe, D 795 17), it is the sound of a hunting horn that speaks of his rejection by the beloved. For those who see Winterreise as the poet offering an alternative, more disturbing ending to Die schöne Müllerin, there is some deliberate parallelism here. A horn blows and he realises that he has blown his chances. Or we could choose to examine the differences between the two stories as embodied by the two horns. The young lad in Die schöne Müllerin is close to nature, to water and the woods. He is a miller, central to agricultural society, but is ousted by a hunter. He cannot compete with all that the hunting horn represents. The traveller in Winterreise, though, is leaving a town rather than a river or the woods. His world is bourgeouis rather than feudal. For him it is the posthorn (symbolising a world of gentility and civilisation) that persuades him of his outsider status.

Note on ‘the post’

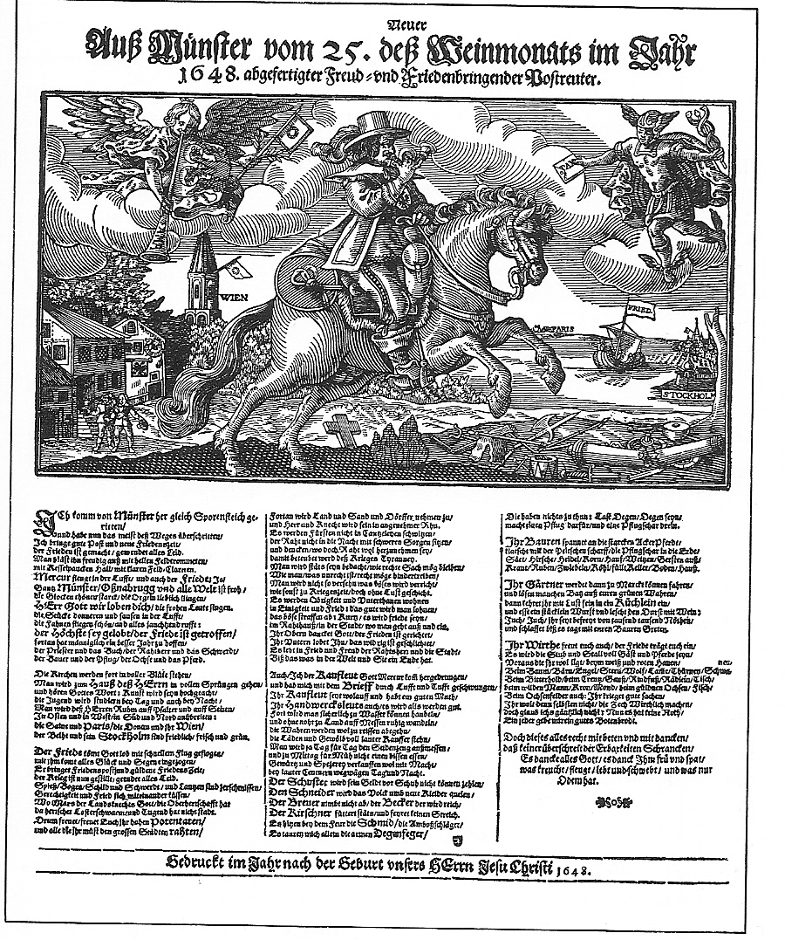

It was the Romans who created the link between the idea of a wooden ‘post’ standing in the ground, soldiers being ‘posted’ to serve in particular places, servants being appointed to a vacant ‘post’ and long-distance couriers who formed a ‘postal’ system. The physical posts marked the links in the relay system, with post-masters in charge of the horses and the rest of the infrastructure that kept the communication system going. The Roman system was revived in northern Europe in the early 16th century, when the Holy Roman Empire set up a postal infrastructure to connect Vienna and Brussels. This system was then farmed out to the Princes of Thurn und Taxis, who operated the post on behalf of the Empire. After the official abolition of the Empire in 1806 and the Congress of Vienna in 1815 the Thurn-und-Taxis Post was appointed as the monopoly provider of postal services throughout the German speaking lands.

To hear a post-horn, go tohttps://www.postalmuseum.org/blog/sound-of-the-post-horn/

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Die Post Von der Straße her ein Posthorn klingt. Was hat es, daß es so hoch aufspringt, Mein Herz? Die Post bringt keinen Brief für dich: Was drängst du denn so wunderlich, Mein Herz? Nun ja, die Post kommt1 aus der Stadt, Wo ich ein liebes Liebchen hatt', Mein Herz! Willst wohl einmal hinüber sehn, Und fragen, wie es dort mag gehn, Mein Herz? 1 Schubert changed 'kömmt' (would be coming) to 'kommt' (is coming)

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten. Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Müller. Zweites Bändchen. Deßau 1824. Bei Christian Georg Ackermann, page 85.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 85 Erstes Bild 99 here: https://download.digitale-sammlungen.de/BOOKS/download.pl?id=bsb10115225