Mystery. To F. Schubert

(Poet's title: Geheimnis. An F. Schubert)

Set by Schubert:

D 491

[October 1816]

Sag an, wer lehrt dich Lieder,

So schmeichelnd und so zart?

Sie rufen einen Himmel

Aus trüber Gegenwart.

Erst lag das Land, verschleiert

Im Nebel vor uns da –

Du singst, und Sonnen leuchten,

Und Frühling ist uns nah.

Den schilfbekränzten Alten,

Der seine Urne gießt,

Erblickst du nicht, nur Wasser,

Wie’s durch die Wiesen fließt.

So geht es auch dem Sänger,

Er singt, er staunt in sich;

Was still ein Gott bereitet,

Befremdet ihn wie dich.

Tell me, who teaches you songs,

Songs that are so flattering and so tender?

They summon a heaven

Out of the overcast present.

At first the veiled land lay

There before us, covered in mist –

You sing – and suns light up,

And spring is close to us.

The old man with a garland of reeds

Who is pouring out his urn,

You do not notice him, just the water

As it flows through the meadows.

That is also how it is with the singer,

He sings, he is amazed;

What a god quietly prepares,

Disconcerts him, as it does you.

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Fields and meadows Heaven, the sky Mist and fog Reeds Rivers (Fluß) Songs (general) Spring (season) Springs, sources and fountains The sun Urns Wreaths and garlands

On 7th September 1816 Johann Mayrhofer wrote to Franz von Schober (who was visiting Sweden) to tell him: “Schubert and several friends are to come to me to-day, and the fogs of the present time, which is somewhat leaden, shall be lifted by his melodies” (Deutsch, Schubert. A documentary biography London 1946 no. 97 p.70). This either anticipates, or quotes, Mayrhofer’s poem in honour of Schubert, with its reference to the ‘overcast present’ and the lifting of the ‘fogs’. We cannot know precisely when ‘Geheimnis’ (‘mystery’ or ‘secret’) was written, but it must have been shortly before Schubert set it to music in October 1816. By that point the 19 year old composer had already written about 300 songs, but he had only recently turned his attention to his friend Mayrhofer’s poetry. A year later they would be living together, and by then Schubert would have composed about 30 songs based on Mayrhofer texts. There can therefore be no doubt that Geheimnis was written with the intention that the dedicatee would set it to music.

There can be no doubt, either, that Mayrhofer was genuinely perplexed by Schubert’s fluency and creativity. Here was someone who was able to lift the gloom, to take us out of the present day and into a less disturbing state of being. Throughout Mayrhofer’s writing, the suffering which characterises our life now, in the present, is in stark contrast to life in the ancient world or to the dimension to which all sensitive souls aspire, probably only attainable in an unearthly future. We even see this tone in the letter to Schober. Mayrhofer anticipates the delight of Schubert’s visit and the effect of his songs. In Geheimnis, the same effect is recalled as an experience in the past. In the present, though, things are murky, the sky is overcast, the fog has not lifted.

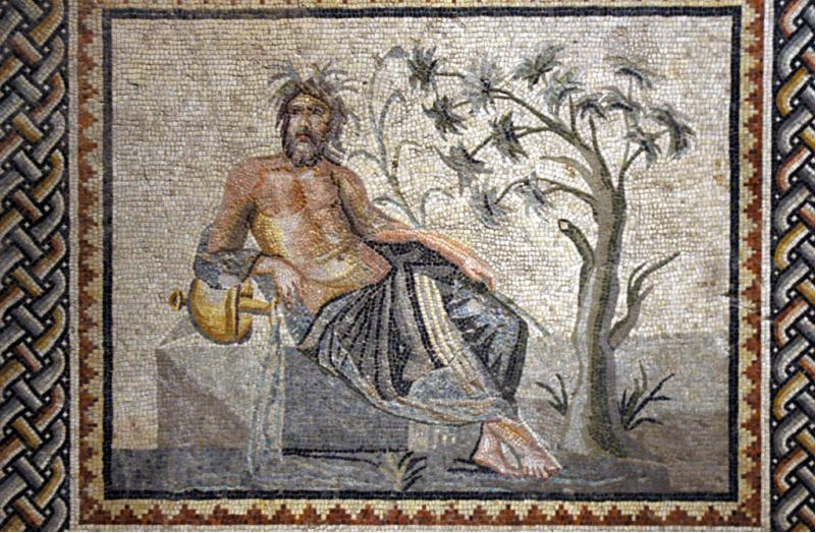

The first, metereological stanza (thick cloud, fog, sunlight, the arrival of spring) gives way to a second stanza where the primary image is a flowing river, symbolizing the fluency of Schubert’s music (a particularly apt association, as all commentaries on his work agree). Schubert, according to the poet, pays no attention to the source of the music / the river, he simply goes with the flow. Mayrhofer, like many of us, would like to know more about where it comes from. He uses the classical image of the ‘potamos’, an old man pouring out an urn to refer to a river’s source and identity. In Homer each river (such as the Acheron or the Cocytus) is itself a god, so the image of the ‘fons et origo’ tries to represent the gushing spring (the upturned urn) and the aged father who are both essential elements in the river’s being. There are still statues of ‘Old Father Thames’ along the course of that river (e.g. at Lechlade and at Richmond) and in 2017 a similar figure was made by Wolfgang Eckert and placed by one of the sources of the Danube. The most famous such sculpture is probably Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in the Piazza Navona in Rome, with the figures of the Nile, the Danube, the Ganges and the River Plata. In all of these cases the old men sit or recline by a gushing source, but the cavity from which the river springs continues to pique our curiosity. What is the relationship between this father and the mother earth from which the river pours? How can this ancient river be so perpetually fresh? It is a mystery.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donauquelle#/media/File:Danuvius-Figur_auf_der_Bregquelle_Donauursprung.jpg

Rome, Piazza Navona, Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi

Photo: Malcolm Wren

☙

Original Spelling and note on the text Geheimniß Sag an, wer lehrt dich Lieder, So schmeichelnd und so zart? Sie rufen1 einen Himmel Aus trüber Gegenwart. Erst lag das Land, verschleyert, Im Nebel vor uns da - Du singst - und Sonnen leuchten, Und Frühling ist uns nah. Den schilfbekränzten Alten, Der seine Urne gießt, Erblickst du nicht, nur Wasser, Wie's durch die Wiesen fließt. So geht es auch dem Sänger, Er singt, er staunt in sich; Was still ein Gott bereitet, Befremdet ihn, wie dich. 1 When the text was published (in 1821 and 1824) this word was 'zaubern' (conjure). It is impossible to know if Schubert made the change or if he was working from an early draft by Mayrhofer.

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Gedichte von Johann Mayrhofer. Wien. Bey Friedrich Volke. 1824, page 9; and with Conversationblatt. Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Unterhaltung. Dritter Jahrgang. 1821. Nr. 69. (Wien, Mittwoch den 29. August) Im Verlage der Gerold’schen Buchhandlung, page 821.

Note: Schubert received Mayrhofer’s texts generally in manuscript; the printed edition of Mayrhofer’s poems appeared much later and presents the texts usually in a revised version.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 821 [239 von 746] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ167347908