Laura at the keyboard

(Poet's title: Laura am Klavier)

Set by Schubert:

D 388

[March 1816]

Wenn dein Finger durch die Saiten meistert, –

Laura, jetzt zur Statue entgeistert,

Jetzt entkörpert steh ich da.

Du gebietest über Tod und Leben,

Mächtig wie von tausend Nervgeweben

Seelen fordert Philadelphia.

Ehrerbietig leiser rauschen

Dann die Lüfte, dir zu lauschen,

Hingeschmiedet zum Gesang

Stehn im ew’gen Wirbelgang,

Einzuziehn die Wonnefülle,

Lauschende Naturen stille,

Zauberin! mit Tönen, wie

Mich mit Blicken, zwingst du sie.

Seelenvolle Harmonieen wimmeln,

Ein wollüstig Ungestüm,

Aus den Saiten, wie aus ihren Himmeln,

Neugeborne Seraphim;

Wie des Chaos Riesenarm entronnen,

Aufgejagt vom Schöpfungssturm die Sonnen

Funkelnd fuhren aus der Nacht,

Strömt der Töne Zaubermacht.

Lieblich jetzt wie über glatten Kieseln

Silberhelle Fluten rieseln,

Majestätisch prächtig nun

Wie des Donners Orgelton,

Stürmend von hinnen jetzt, wie sich von Felsen

Rauschende schäumende Gießbäche wälzen,

Holdes Gesäusel bald,

Schmeichlerisch linde,

Wie durch den Espenwald

Buhlende Winde,

Schwerer nun und melancholisch düster,

Wie durch toter Wüsten Schauernachtgeflüster,

Wo verlornes Heulen schweift,

Tränenwellen der Kocytus schleift.

Mädchen, sprich! Ich frage, gib mir Kunde,

Stehst mit höhern Geistern du im Bunde?

Ist’s die Sprache, lüg mir nicht,

Die man in Elysen spricht?

When your fingers take control of the strings,

Laura, I am at the same time turned into a lifeless statue

And a spirit outside of its body as I stand there.

You command both death and life,

You are powerful, like [Jacob] Philadelphia

Demanding a thousand souls woven from nerves!

They are more gentle as they show homage, those rustling

Breezes, so that they can listen to you;

Welded to the song

The eternal turmoil stands still,

Breathing in the fullness of joy,

Listening nature is quiet.

Sorceress! You use notes, in the same way

That you use glances on me, to control them.

Soulful harmonies are bursting out,

A voluptuous impetuosity

Comes out of the strings, like

Newborn Seraphim coming out of their heaven;

As, having escaped the giant arms of Chaos,

Driven away by the storm of creation, the suns

Went off shining out of the night,

Similarly the magical power of the notes streams forth.

Lovingly now, as over smooth pebbles

Silver-bright waters trickle,

Now majestically splendid,

Like the tone of an organ, like thunder,

Pouring down now, as if over a cliff,

Like rushing, frothing torrents, rolling,

Suddenly a beauteous murmuring,

Flatteringly gentle,

Like seductive winds blowing through

Aspen woods,

Heavier now, and more serious and melancholy,

Like terrifying night whispering through dead wastelands

Where lost howling souls wander,

Where Cocytus drags its waves of tears.

Girl, speak! I beg you, let me know:

Are you in league with higher spirits?

Do not lie to me, is that the language

That they speak in Elysium?

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Angels Deserts Elysium Fingers Floods and tides Harmony Heaven, the sky Lethe Listening Magic and enchantment Melancholy Moving around (schweifen) Night and the moon Organs Pianos and keyboards Pulling and dragging Rivers (Bach) Rivers – waterfalls, rapids and whirlpools Silver Smiths and metalwork Soul Stones and pebbles Storms Stringed instruments (unspecified) Tears and crying Thunder and lightning The underworld (Orcus, Hades etc) Waves – Welle Whispering Walking and wandering Wind

Schiller wrote this text (along with his other ‘Laura’ poems) at the beginning of his literary career, when he was part of the movement that came to be called ‘Sturm und Drang’ (Storm and Impulse). Laura’s playing is presented as something that creates storms and passionate drives within the listener. She appears to the poet as some sort of conjuror or enchantress who can control the souls of her audience with the lightest touch of her fingers on the keys.

We have to remember that in 1781 the fortepiano or harpsichord that she would have been playing was incapable of the range of dynamics that seem to be described in Schiller’s poem. This was half a century before people swooned at Liszt’s piano recitals or attributed Paganini’s violin playing to supernatural forces. It was a generation before the sort of pianoforte for which Beethoven wrote his sonatas. Indeed the ‘storm’ that interrupts Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony (1808) probably sounds less turbulent to us than the experience evoked by Laura’s playing as presented by Schiller. We therefore have to conclude that the poem is offering us a view into the inner life of a sensitive listener rather than a description of the sounds heard in the salon.

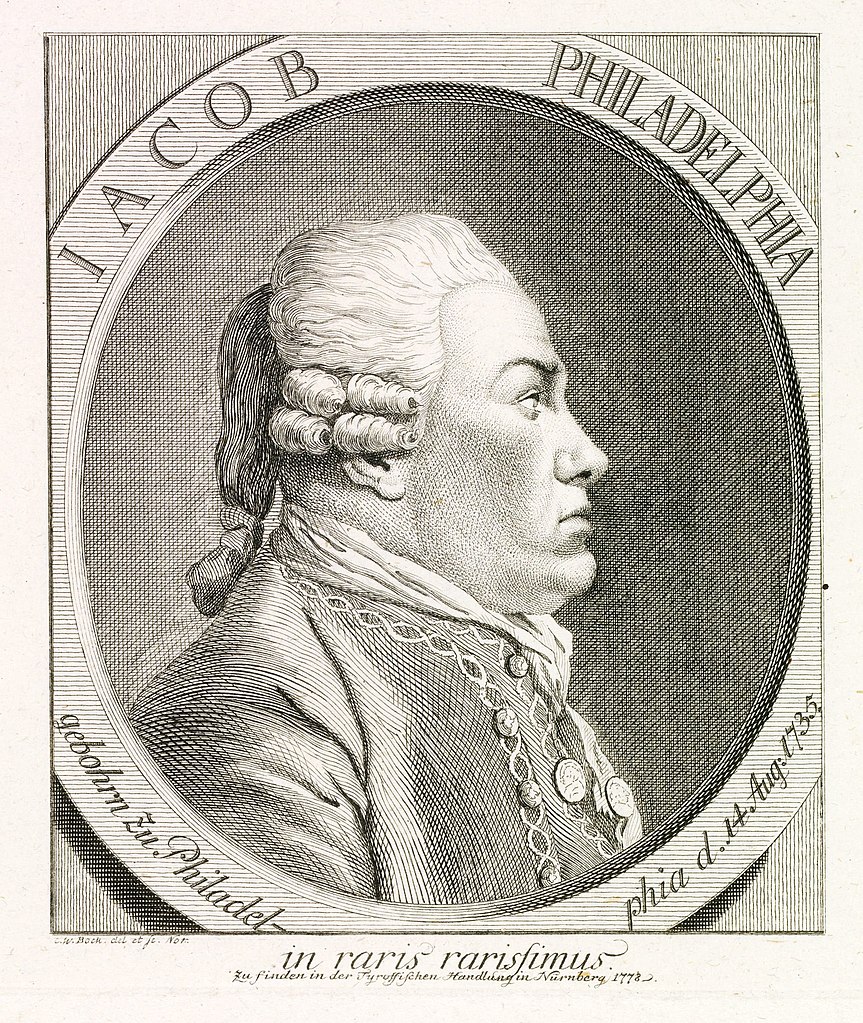

The poet feels that his spirit has left his body and is not sure whether he is now an inanimate statue or a disembodied soul looking on the scene from outside. This is the sort of mind control or hypnosis that was practised by Jacob Philadelphia[1] at the time (a few years before Mesmer’s similar ‘cures’ were parodied in Mozart’s Così fan tutte). Her powers are in that strange realm between science and conjuring that we would today probably associate with alternative therapies but in the late 18th century, when demonstrations of the power of electricity and magnetism could produce both mystical awe and genuine scientific curiosity, her performance appealed to every aspect of the soul: intellectual, aesthetic and spiritual.

The language then turns metereological. Breezes are stilled in order to listen to the music; spiralling weather systems are hammered into paying attention (the mixed metaphors presumably tell us something of the turbulence in the poet’s mind as he tries to make sense of what is happening).

Now comes a burst of cosmology. In imagery that is still used by astronomers, stars (suns) are described as being ‘born’ or escaping from the ‘grip’ of Chaos. Laura’s playing is not just a reflection of the eternal ‘music of the spheres’ (the Aristotelean or steady-state theory of the cosmos) but a way of connecting us to the mystery of creation itself. (Schiller would have been horrified that the burst of creativity he experienced has come to bear the unmusical name of the ‘big bang’, though).

Laura’s fingers transform the sparkling starlight into rippling water. It begins gently, burbling over pebbles, but soon encounters larger rocks and falls as a cascade into whirlpools before slowing down again. Yet another transformation of the elements turns the music from water to air. The listener now hears seductive winds before the mood changes and night whispers as lost souls howl in the desert. The river we have followed is the Cocytus, a tributary of the Styx, whose water is made up of the tears of doomed humanity. How can a young woman’s delicate fingers touching a simple keyboard create such a spectrum, ranging from Heaven to Hell, from Creation to Doomsday, unless she is in league with higher powers? She has managed to communicate in an alien language, which can only be the language of the gods. Schiller does not specify which gods, but we can be in little doubt that Eros was involved.

[1] Jacob Meyer (1735 – 1795) adopted the surname Philadelphia in honour of Benjamin Franklin, one of the most famous residents of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the 1770s and 1780s he toured Europe (going as far as Constantinople and St. Petersburg) performing a magic show based on his Rosicrucian and alchemical ideas.

☙

Original Spellling and notes on the text

Laura am Klavier

Wenn dein Finger durch die Saiten meistert -

Laura, jetzt zur Statue entgeistert,

Jetzt entkörpert steh' ich da.

Du gebietest über Tod und Leben,

Mächtig wie von tausend Nervgeweben

Seelen fordert Philadelphia -

Ehrerbietig leiser rauschen

Dann die Lüfte, dir zu lauschen

Hingeschmiedet zum Gesang

Stehn im ew'gen Wirbelgang,

Einzuziehn die Wonnefülle,

Lauschende Naturen stille,

Zauberin! mit Tönen, wie

Mich mit Blicken, zwingst du sie.

Seelenvolle Harmonieen wimmeln,

Ein wollüstig Ungestüm,

Aus den Saiten, wie aus ihren Himmeln

Neugebor'ne Seraphim;

Wie des Chaos Riesenarm entronnen,

Aufgejagt vom Schöpfungssturm die Sonnen

Funkelnd fuhren aus der Nacht,

Strömt der Töne Zaubermacht.

Lieblich jetzt, wie über glatten Kieseln

Silberhelle Fluthen rieseln, -

Majestätisch prächtig nun

Wie des Donners Orgelton,

Stürmend von hinnen jetzt wie sich von Felsen

Rauschende schäumende Gießbäche wälzen,

Holdes Gesäusel bald,

Schmeichlerisch linde,

Wie durch den Espenwald

Buhlende Winde,

Schwerer nun und melancholisch düster,

Wie durch todter Wüsten Schauernachtgeflüster,

Wo verlor'nes Heulen schweift,

Thränenwellen der Kocytus schleift.

Mädchen, sprich! Ich frage, gieb mir Kunde,

Stehst mit höhern Geistern du im Bunde?

Ist's die Sprache, lüg' mir nicht,

Die man in Elysen spricht?

1 NSA: second version (Zweite Fassung) only: 'aufgestreckt' replaces 'aufgejagt'

Schiller's first version of the text was longer, and he made some other minor changes before he produced the version as set by Schubert. Here is the original, with the changes and extra two stanzas in italics:

Wenn dein Finger durch die Saiten meistert,

Laura, itzt zur Statue entgeistert,

Itzt entkörpert steh ich da.

Du gebietest über Tod und Leben,

Mächtig, wie von tausend Nervgeweben

Seelen fordert Philadelphia!

Ehrerbietig leiser rauschen

Dann die Lüfte, dir zu lauschen;

Hingeschmidet zum Gesang

Stehn im ewgen Wirbelgang,

Einzuziehn die Wonnefülle,

Lauschende Naturen stille.

Zauberin! mit Tönen, wie

Mich mit Blicken, zwingst du sie.

Seelenvolle Harmonien wimmeln,

Ein wollüstig Ungestüm,

Aus den Saiten, wie aus ihren Himmeln

Neugebohrne Seraphim;

Wie des Chaos Riesenarm entronnen,

Aufgejagt vom Schöpfungssturm, die Sonnen

Funkend fuhren aus der Finsternuß,

Strömt der goldne Saitengruß.

Lieblich itzt, wie über bunten Kieseln

Silberhelle Fluten rieseln,

Majestätisch prächtig nun,

Wie des Donners Orgelton,

Stürmend von hinnen itzt, wie sich von Felsen

Rauschende, schäumende Gießbäche wälzen,

Holdes Gesäusel bald,

Schmeichlerisch linde,

Wie durch den Espenwald

Buhlende Winde,

Schwerer nun und melancholisch düster,

Wie durch todter Wüsten Schauernachtgeflüster,

Wo verlornes Heulen schweift,

Thränenwellen der Kozytus schleift.

Mädchen, sprich! Ich frage, gib mir Kunde:

Stehst mit höhern Geistern du im Bunde?

Ists die Sprache, lüg mir nicht,

Die man in Elysen spricht?

Von dem Auge weg der Schleyer!

Starre Riegel von dem Ohr!

Mädchen! Ha! schon athm´ ich freier,

Läutert mich ätherisch Feur?

Tragen Wirbel mich empor? -

Neuer Geister Sonnensitze

Winken durch zerrißner Himmel Rize -

Überm Grabe Morgenroth!

Weg, ihr Spötter, mit Insektenwize!

Weg! Es ist ein Gott - -

Confirmed by Peter Rastl Friedrich Schillers sämmtliche Werke. Zehnter Band. Enthält: Gedichte. Zweyter Theil. Wien, 1810. In Commission bey Anton Doll. [korrigierter Druck] pages 64-65; and with Gedichte von Friederich Schiller, Zweiter Theil, Zweite, verbesserte und vermehrte Auflage, Leipzig, 1805, bei Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius, pages 85-87.

First published in Anthologie auf das Jahr 1782, anonymously edited by Schiller with the fake publishing information “Gedrukt in der Buchdrukerei zu Tobolsko”, actually published by Johann Benedict Metzler in Stuttgart. This poem (pages 19-21) has two more stanzas (see above) and differs in some other ways from the final version. It was published with “Y.” as the author’s name.

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 64 [70 von 310] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ207858305