Serenade

(Poet's title: Ständchen)

Set by Schubert:

D 889

[July 1826]

Horch, horch, die Lerch im Ätherblau,

Und Phöbus, neu erweckt,

Tränkt seine Rosse mit dem Tau,

Der Blumenkelche deckt;

Der Ringelblume Knospe schleußt

Die goldnen Äuglein auf;

Mit allem, was da reizend ist,

Du süße Maid, steh auf,

Steh auf, steh auf.

Listen, listen to the lark in the ethereal blue!

And Phoebus, newly awakened,

Leading his horses to drink the dew

That covers the calyces of the flowers;

The buds of the marigolds are beginning to open

Up their little golden eyes;

With everything that is charming there,

Oh sweet maid, get up!

Get up! Get up!

All translations into English that appear on this website, unless otherwise stated, are by Malcolm Wren. You are free to use them on condition that you acknowledge Malcolm Wren as the translator and schubertsong.uk as the source. Unless otherwise stated, the comments and essays that appear after the texts and translations are by Malcolm Wren and are © Copyright.

☙

Themes and images in this text:

Apollo / Phoebus Blue Buds Cups and goblets Dew Ether Eyes Flowers Gold Horses Larks Morning and morning songs Serenades and songs at evening Stars Waking up

King Cymbeline’s daughter Imogen (Innogen in recent editions) is being pursued by Cloten, her step-mother’s son by a former husband. Act II Scene 3 of the play begins as follows:

Enter CLOTEN and [the two] Lords.

First Lord Your lordship is the most patient man in loss, the most coldest that ever turned up ace.

Cloten It would make any man cold to lose.

First Lord But not every man patient after the noble temper of your lordship. You are most hot and furious when you win.

Cloten Winning will put any man into courage. If I could get this foolish Innogen, I should have gold enough. It's almost morning, is't not?

First Lord Day, my lord.

Cloten I would this music would come: I am advised to give her music o' mornings; they say it will penetrate.

Enter musicians [with stringed instruments]

Come on, tune. If you can penetrate her with your fingering, so; we'll try with tongue, too: if none will do, let her remain: but I'll never give o'er. First, a very excellent good-conceited thing; after a wonderful sweet air with admirable rich words to it; and then let her consider.

SONG

Musician Hark, hark, the lark at heaven's gate sings,

And Phoebus 'gins arise,

His steeds to water at those springs

On chaliced flowers that lies,

And winking Mary-buds begin to ope their golden eyes.

With every thing that pretty is, my lady sweet, arise,

Arise, arise.

Cloten So, get you gone. If this penetrate, I will consider your music the better; if it do not, it is a voice in her ears which horsehairs and calves' guts, nor the voice of unpaved eunuch to boot, can never amend.

[Exeunt Musicians.]

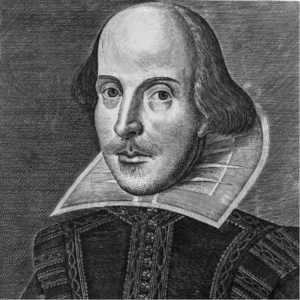

William Shakespeare, Cymbeline Act II Scene 3 lines 1 - 31 Edited by Valerie Wayne (The Arden Shakespeare 2017)

The original context shows that the text should never have been called a ‘serenade’. Technically, it is an ‘aubade’, a song performed outside the beloved’s chamber in the morning rather than the evening. Shakespeare has filled it with the imagery of daybreak: the lark ascending, Phoebus / Apollo (the sun god on his chariot pulled by horses) climbing in the east, dew cupped in flowers and marigolds (golden like the sun) opening their buds.

Peter Rastl has found that the German translation set by Schubert should never have been attributed to Schlegel, even though this is the text that appeared in the 1825 Vienna edition of Schlegel’s Cymbelin. It was taken word for word from Abraham Voß´s translation, published in Tübingen in 1810. Voß decided to prioritise rhyme rather than sense, which explains some of the changes. In the German version we do not have ‘the lark at heaven’s gate’, since the ‘sings’ / ‘springs’ rhyme will not work in German. Instead Voß offers ‘blue’ / ‘dew’ (blau / Tau), thus creating the memorable ‘die Lerch’ im Ätherblau’. Although some of the vividness of Shakespeare’s language inevitably disappears in translation (the Mary-buds are not ‘winking’, for example) we have to admire Voß’s ‘Blumenkelche’ (flower chalices / calyces) for ‘chaliced flowers’. Botanists and etymologists might insist that the word ‘calyx’ is based on the Latin (and Greek) word for ‘bud’ and should not be confused with ‘calix’ (cup or beaker), but Shakespeare could not resist the word play. The idea of Phoebus’s horses drinking from the tiny chalices of the flowers evoked associations with the chalices used in holy communion. Those who argue that Shakespeare was a closet Catholic (or simply that he never forgot the mainly Catholic piety that surrounded him as a child) might also argue that the choice of flower is equally symbolic. Marigolds are called ‘Mary-buds’. It is a shame that Voß was not able to capture that association in the German version.

☙

Shakespeare (First Folio, 1623)

Hearke, hearke, the Larke at Heavens gate sings,

and Phœbus gins arise,

His Steeds to water at those Springs

on chalic’d Flowres that lyes:

And winking Mary-buds begin to ope their Golden eyes

With every thing that pretty is, my Lady sweet arise:

Arise arise.

Voß’s German

Horch! horch! die Lerch’ im Ätherblau;

Und Phöbus, neu erweckt,

Tränkt seine Rosse mit dem Thau,

Der Blumenkelche deckt;

Der Ringelblume Knospe schleußt

Die goldnen Äuglein auf;

Mit allem, was da reizend heißt,

Du süße Maid, steh auf!

Steh auf! steh auf!

Back translation

Listen, listen to the lark in the ethereal blue!

And Phoebus, newly awakened,

Leading his horses to drink the dew

That covers the calyces of the flowers;

The buds of the marigolds are beginning to open

Up their little golden eyes;

With everything that is charming there,

Oh sweet maid, get up!

Get up! Get up!

Original Spelling and note on the text Ständchen Horch! horch! die Lerch' im Ätherblau; Und Phöbus, neu erweckt, Tränkt seine Rosse mit dem Thau, Der Blumenkelche deckt; Der Ringelblume Knospe schleußt Die goldnen Äuglein auf; Mit allem, was da reizend ist1, Du süße Maid, steh auf! Steh auf! steh auf! 1 Schubert changed 'heißt' (is called) to 'ist' (is)

Confirmed by Peter Rastl with Schubert’s source, William Shakspeare’s sämmtliche dramatische Werke übersetzt im Metrum des Originals. XXVI. Bändchen. Cymbelin, von A.W.Schlegel. Wien. Druck und Verlag von J. P. Sollinger. 1825, page 33; with Schauspiele von William Shakspeare [sic] übersezt von Heinrich Voß und Abraham Voß. Erster Theil. Tübingen in der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. 1810, page 173; and with William Shakspeare’s sämmtliche dramatische Werke und Gedichte. Uebersetzt im Metrum des Originals in einem Bande nebst Supplement, […] Wien. Zu haben bei Rudolph Sammer, Buchhändler. Verlegt bei J. P. Sollinger, 1826, page 606.

Note: The poem is Cloten’s song in Cymbelin, act 2, scene 3. The German translation is by Abraham Voß (brother of Heinrich Voß and son of Johann Heinrich Voß), as is explained in the preamble of their 1810 book. This translation was adopted by A. W. Schlegel in the complete edition of his Shakespeare translations, without giving credit to the actual translator. In fact, the 1826 edition specifies A. W. Schlegel as the translator.

Note: When Schubert’s song was published posthumously in 1832 (Philomele eine Sammlung der beliebtesten Gesänge mit Begleitung des Pianoforte eingerichtet und herausgegeben von Anton Diabelli. No. 294), the editor commissioned Friedrich Reil to create two additional stanzas which were then carried over by Max Friedlaender into his Schubert Album (Peters Edition).

To see an early edition of the text, go to page 33 [41 von 126] here: http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ178572304